By Associated Press

MARTY, S.D. (AP) — As the Yankton Sioux transportation planner, Wesley Hare Jr. received reports of a dangerous intersection often used by tribal members.

Accidents and near-misses were occurring because of a blind spot near the junction of S.D. Highway 46 and a Bureau of Indian Affairs road leading to Marty, Hare said.

Hare contacted the South Dakota Department of Transportation about the problem.

“A (DOT) person was out there, and he observed for a week and saw the near misses,” the tribal planner said.

A road turnout was constructed for safety reasons, Hare said. “We have gotten a lot of feedback and good comments on it,” he added.

The Yankton Sioux isn’t the only tribe with such issues. Transportation needs remain a challenge for Indian Country. In order to share their experiences, nine tribes from across South Dakota have created the Tribal Transportation Safety Summit.

The Yankton Sioux Tribe recently hosted the fourth annual summit at Fort Randall Casino. The two-day meeting drew around 100 officials — double the first summit and the largest turnout in the event’s history, Hare said.

The nine tribes that took part were the Rosebud, Oglala, Crow Creek, Lower Brule, Standing Rock, Cheyenne River, Flandreau, Sisseton-Wahpeton and Yankton.

The Yankton Sioux highway department not only cares for tribal roads but also partners with Charles Mix County and the state’s transportation department, he said. “As far as tribal roads, we have only 28 miles. But in conjunction with the county and state, we have maybe 1,200 miles,” he said.

During last month’s highway summit, Hare learned of the vast road miles that other tribes maintain.

“Marty to Greenwood is only six miles for us,” he said. “But communities (in other parts of South Dakota) may be 30 to 50 miles apart, and they have to take care of those long stretches.”

The Federal Highway Administration has encouraged these types of tribal conferences across the nation, according to June Hansen the tribal liaison of the state’s transportation department.

“During the annual meetings that SDDOT holds with each of the nine tribes, the topic of transportation safety and ideas to improve safety was a recurring theme,” she said. “The SDDOT was happy to partner with the nine tribes and a number of other agencies (on setting up the summit).”

Those agencies include the federal transportation agency’s South Dakota division office, Bureau of Indian Affairs, South Dakota Department of Public Safety and the Northern Plains Tribal Transportation Assistance Program.

“The real heart of each of these summits is the host tribe, and all the host tribes have done an outstanding job with each of the summits,” Hansen said. “That is especially true for Wesley Hare and his staff with the Yankton Sioux Tribe. They really outdid themselves with some truly unique and special events like the honoring of the YST Code Talkers from World Wars I and II.”

At last month’s summit, the tribes also talked about cooperation between their road and police departments to cut down on drunk driving and related fatalities.

The Yankton Sioux presentation was given by Hare and Louis Golus Jr., the road maintenance supervisor. Besides the Highway 46 turnout, Yankton Sioux Tribe successes include the installation of reflectors around Marty and the road leading to Greenwood.

Among other projects, the Yankton Sioux Tribe has worked with other entities on a Lake Andes walkway and welcome signs around Charles Mix County, acknowledging the Yankton Sioux traditional homeland.

In addition, the transit program, started in 2011, has grown rapidly, Hare said. The transit operates 18 hours daily, running a route of 16 stops. The tribe constructed 14 shelters for passenger waiting for rides.

Passengers rely on the transit for reaching destinations ranging from jobs and medical appointments to the Boys and Girls Club and Fort Randall Casino.

“Forty-five percent of our people don’t have any (personal) transportation at all,” he said. “The transit is a really growing program. The first year, during a month’s time, we had between 500 and 600 riders. Now, we are over 2,000 riders a month. It has just shot up.”

In his work with the federal government, Hare noted a shift from the Bureau of Indian Affairs to tribes. Tribes now take care of planning, hiring their own engineers and doing their own construction. In addition, funding goes directly to tribes rather than funneled through the bureau.

That isn’t to say the bureau and tribes have become disengaged, Hare said. “We keep in touch with the BIA in Aberdeen. We still use them for a lot of technical assistance,” he said.

Hare was elected chairman for the Northern Plains Tribal Technical Assistance Program, which serves 26 tribes. Adequate funding remains a concern at all levels, he said.

In that respect, the annual highway summits take on growing importance as tribes make the most of their resources, Hansen said.

“The networking between the various tribal agencies that work to improve transportation safety — whether they are from the engineering, education, enforcement or emergency services — has grown each year,” she said.

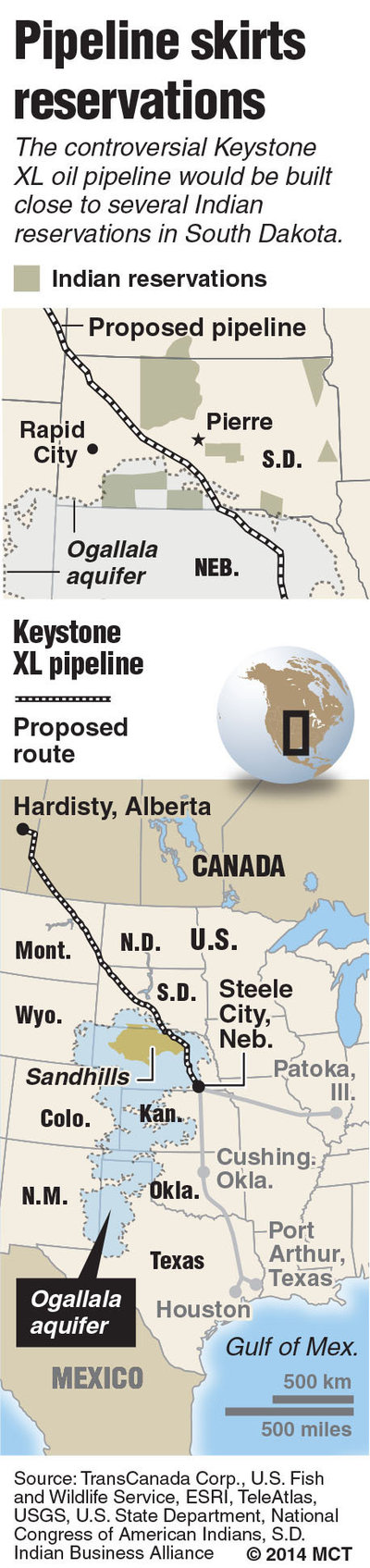

“If you like to drink water, if you like your children not being harmed, if you don’t want your women being harmed, then say no to the pipeline,” Grey Cloud said. “Because once it comes, it’s going to destruct everything.”

“If you like to drink water, if you like your children not being harmed, if you don’t want your women being harmed, then say no to the pipeline,” Grey Cloud said. “Because once it comes, it’s going to destruct everything.”