By Kalvin Valdillez, Tulalip News

If you look up the word resiliency in the dictionary there will be a picture of the Tulalip leader, Harriette Shelton-Dover. Or at least there should be, because she is the very definition of the word. Harriette was a boarding school survivor, cultural preserver and language revivalist. She was a highly respected leader as well as a daughter, mother, cousin, auntie and grandmother of the Tulalip people. Harriette restored the practice of the Salmon Ceremony, testified during the Boldt decision and was the first chairwoman of the Tulalip Tribes – to name a few of her accomplishments. But perhaps one of Harriette’s biggest accomplishments was rebuilding pride in a tribal community during and after years of forced assimilation. She knew her language, rights and culture and stressed the importance of both practicing those traditions as well as passing them down to the next generation. Harriette passed on to the next life in 1991, yet her teachings continue to inspire generation after generation.

Despite her boarding school experience, Harriette knew the importance of an education and received her college degree from Everett Community College during the seventies, while in her seventies. While attending the college, Harriette met Darleen Fitzpatrick, a young Anthropology Professor who was teaching a course on Northwest Coast tribes.

“The beginning of one fall quarter, I was standing in front of the room getting ready to start class and I just happen to look over at the door and she just happened to walk in at that moment,” recalls Social Anthropologist Darleen Fitzpatrick. “With her cane thumping on the floor, she stopped halfway to me and said ‘I want to know what you’re saying about Indians’. Thumping with her cane, she thumped over to the front row and sat down exactly in front of me. Looking at her I thought well, if there’s anything wrong this is how I’m going to find out. I was twenty-eight years old and she was seventy. When she said, ‘I want to know what you’re saying about Indians’, that began a relationship that eventually became a friendship. As we were becoming acquainted, I finally said to her, ‘I can help you with the history you want to do about Tulalip. We have tape recorders; we can do it on Friday afternoons before I go home’. So that’s what we did for quite a while.”

Darleen spent every Friday, for two years, recording Harriette as she shared the history of Tulalip as well as some of her personal experiences. In total, there were nearly two hundred cassette tapes, filled with audio recordings on both sides. After years of transcribing, editing and placing Harriette’s accounts in chronological order, Harriette’s memoirs were published by the University of Washington Press in 2013, twenty-two years after her passing, in the book titled Tulalip, From My Heart: An Autobiographical Account of a Reservation Community.

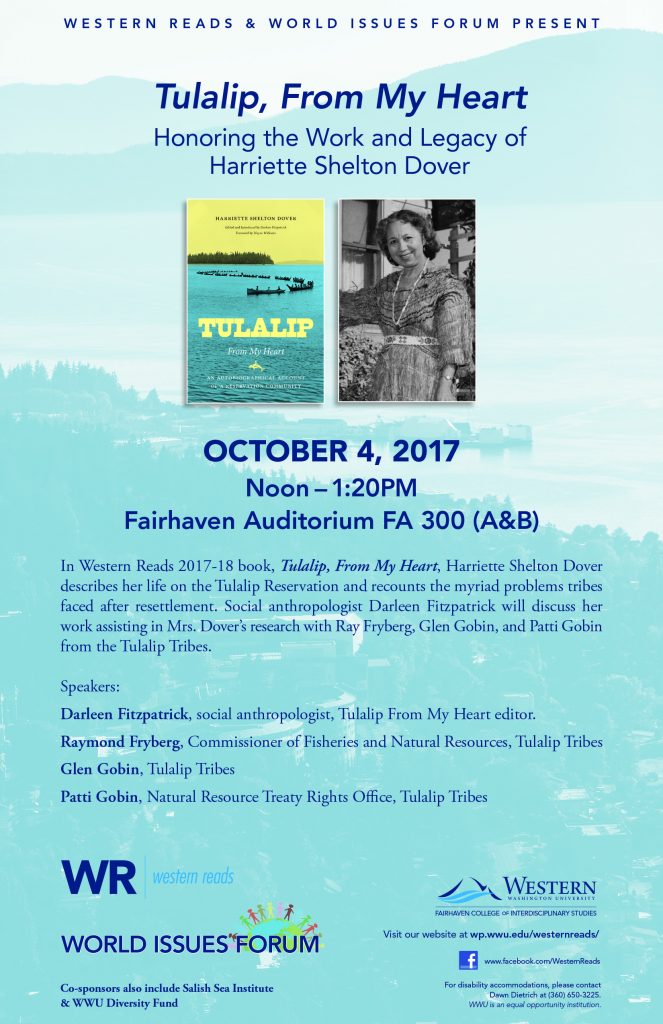

Western Reads is a reading group designed for the new students of Western Washington University. The book club promotes intellectual engagement through a variety of events and activities. Every year, Western Reads collectively decides which book they will be reading; for this year’s selection, the group chose Harriette’s From My Heart.

“We feel that in the past Western has not done a good job of acknowledging the Indigenous culture. This is an opportunity for everyone to reflect on this history of this area and how this history is represented,” states Dawn Dietrich, Director of Western Reads.

Western Reads hosted a forum on October 4, at the Fairhaven Auditorium. During the forum, the reading group witnessed guest speakers Darleen Fitzpatrick, Ray Fryberg and Patti Gobin recount the life and times of Harriette Shelton-Dover. Ray spoke of the boarding school atrocities and shared a little bit of Harriette’s experience at the school.

“She talks about being raised by her grandmother,” says Ray. “The teachings that she got from her grandmother; being introduced out into the woods to the four directions, how to sit properly in the longhouse because people are going to look at you to see how you were taught, because your teachings reflect on your elders. Then she went to the boarding school. She said that during her experience at the boarding school, two boys from Lummi ran away and she knew that they went out and caught them so she and [the other students] had to go back to their dormitories. They all looked out the window, down at the school, to see what they were going to do to the two boys that ran away – they whipped them so hard that it took them forty-five minutes to crawl from the school to the dormitory which was only a quarter of a block.

“They said no speaking Indian – no Indian,” Ray continues “[Harriett] and two girls from Lummi were in the bathroom, they were talking Indian and the matron came in and said ‘didn’t I tell you no talking Indian?’ Harriette said they had a whip – she described it: two inches wide, an inch thick and it had brass tacks – outlawed in the prisons yet they were allowed to be used in the school. She said, ‘the matron whipped me all the way across the bathroom hitting me underneath my ear, across my neck. But there were two things I wouldn’t let that white lady do, I wouldn’t let her knock me down and I wouldn’t let her see me cry. I caught myself in the corner and I grabbed a hold of the sink and I would not let her knock me down.’”

Ray expressed that Harriette knew of the long-term damage Native America faced due to the boarding schools. “She also said, ‘everybody I went to the school with turned out to be alcoholics. I can’t blame them. Out here we don’t have no doctors, no psychologist, no psychiatrist like they do in town.’ We were talking about that back in the mid-eighties before boarding school experiences and generational trauma were even buzzwords. For me, when I read that about the boys, I cried. When I heard about her being whipped, I become really angry that anybody would ever treat a grandmother like that.”

Patti Gobin is Harriette Shelton-Dover’s grandniece. Patti explained that the boarding school experience left many Native Americans across the nation lost, including her grandmother, Celum Young.

“My grandma, she was so broken, split between two worlds: being ‘civilized’ and uncivilized,” explains Patti. “I say that in a good way because that describes my grandma. Uncivilized being something very bad and civilized meaning something you needed to attain. My grandma was first generation in the boarding school, her first language was Lushootseed, her first culture was Coast Salish; and in the blink of an eye she was no longer Coast Salish, she was no longer Indian. She was going to be Catholic, her name was now Cecilia and she was going to speak the English language.

“But this isn’t about my grandma,” she continues. “It’s leading up to how Harriette Shelton-Dover came into my life. She came and knocked on my mom and dad’s door when I was ten years old – that was fifty-four years ago. My dad answered the door and asked ‘what do you want Harriette?’ and she responded, ‘I would like to speak with Celum’ – she never called her Cecilia, it was always Celum. She stepped into the house and my grandma was very quiet, very shy. [Harriett] said ‘I want to ask if I can take your granddaughter, because she has ears to hear and I see something in her.’

“My grandma wasn’t happy because culturally you don’t take someone’s granddaughter out of the house physically and have her stay at your house,” says Patti. “My grandma finally asked ‘why do you want my granddaughter?’ and Harriette said, “because she has something and I think I can share our culture, our history as Tulalip people, as Snohomish people with her.’ My grandma said ‘you can have her, but only on the weekends.’ So, I lived with Harriette Shelton-Dover Friday through Sunday from the time I was ten until I was eighteen. I didn’t think I was learning anything. You may not think you’re absorbing your family’s qualities, traits, their values but you are. Even when you’re fighting, even at a young age when you may not want to be like your mom and dad or your grandma and grandpa – but you end up there. I’m sixty-four and I’m there. I am Harriette, I am Celum, I am many of those elders who took their time and invested in me.”

Patti explained the many lessons she learned from Harriette, or as she called her granny, “the first thing she did was try to teach me how to act Si’ab, high class, how to conduct myself in public. I was shy like my grandma and granny would say ‘look at me, look me in the eye. I want you to tell me who you are and where you come from.’

Patti explained the importance of introductions within the tribal community. She demonstrated how she first introduced herself to Harriette, looking down at the ground in a soft-spoken voice.

“She said ‘lift your head up. Look at me and let’s try this again.’ I looked at her and she said ‘never be ashamed of who you are and where you come from. You are an Indian girl and you must be proud of that. When you walk into a room, you hold your head up high, even though you’re shaking and quaking on the inside. You look people right in the face and say I’m Patti Gobin. My mother is Dolores Gobin and my father is Bernie Gobin. My grandmother is Celum Young, her mother was Lucy McClean-Young, her father was George Young.’”

The entire crowd was moved by Patti’s story, many book club members were in tears while listening to Ray and Patti reflect on the impact Harriette left for the future generations of Tulalip.

“What granny taught me was the beginning of a lifelong lesson – that I am Coast Salish,” states Patti. “I have thirteen grandchildren who are Coast Salish and they know that. As soon they came into this world they knew that they’re Coast Salish. They sing our songs and know that they’re members of the Tulalip Tribes and they’re not ashamed. I don’t speak my language, but my grandkids speak the language. My granny preserved our language and our songs in order to pass them on. I went to the University of Washington and ordered From My Heart before it even came out; I don’t even know how I heard about it but I paid full price for the book. It took me a long time, I read two pages at time and cried the whole time because it’s everything she’s ever said to me. I read everything in her voice – she’s always with me. I want to thank Darleen for this marvelous documentation because this will help each generation heal more and more over time.”

The forum ended with a performance of one of Harriette’s songs by Ray and Patti accompanied by Patti’s daughter, Chelsea Craig.

“I think the event was amazing,” says Dawn. “It was so moving not only to read Harriette Shelton-Dover’s account of the Tulalip culture and the region that we all share here, but then to actually hear members of the Tulalip tribe come with very personal connections to Harriette; who knew her, who knew her voice, who knew her songs; and to share that intergenerational wound that people have from everything that happened 150 years ago. There weren’t a lot of dry eyes in the room, particularly when Patti and Ray were speaking and when they were performing the song.

“I feel that people can have misunderstandings of other groups of people when they don’t share a culture,” she continues. “But when you’re face to face and someone has the courage to speak so directly to an audience and to share things so close to their hearts – it moves people. Not intellectually necessarily, but it moves their hearts and that is really the source of education. I felt it was very powerful and I couldn’t have asked for more. I think for students to have the ability to hear this culture and history first hand and hear about how the people today are living with that is invaluable. If it can open hearts and minds and open peoples understanding to an accurate historical account of what actually happened, then the program this year will have been completely worth everything we’ve done to organize it.”