People are now used to long-term weather forecasts that predict what the coming winter may bring. But University of Washington researchers and federal scientists have developed the first long-term forecast of conditions that matter for Pacific Northwest fisheries.

By Hannah Hickey | University of Washington News and Information

September 4, 2013

“Being able to predict future phytoplankton blooms, ocean temperatures and low-oxygen events could help fisheries managers,” said Samantha Siedlecki, a research scientist at the UW-based Joint Institute for the Study of the Atmosphere and Ocean.

“This is an experiment to produce the first seasonal prediction system for the ocean ecosystem. We are excited about the initial results, but there is more to learn and explore about this tool – not only in terms of the science, but also in terms of its application,” she said.

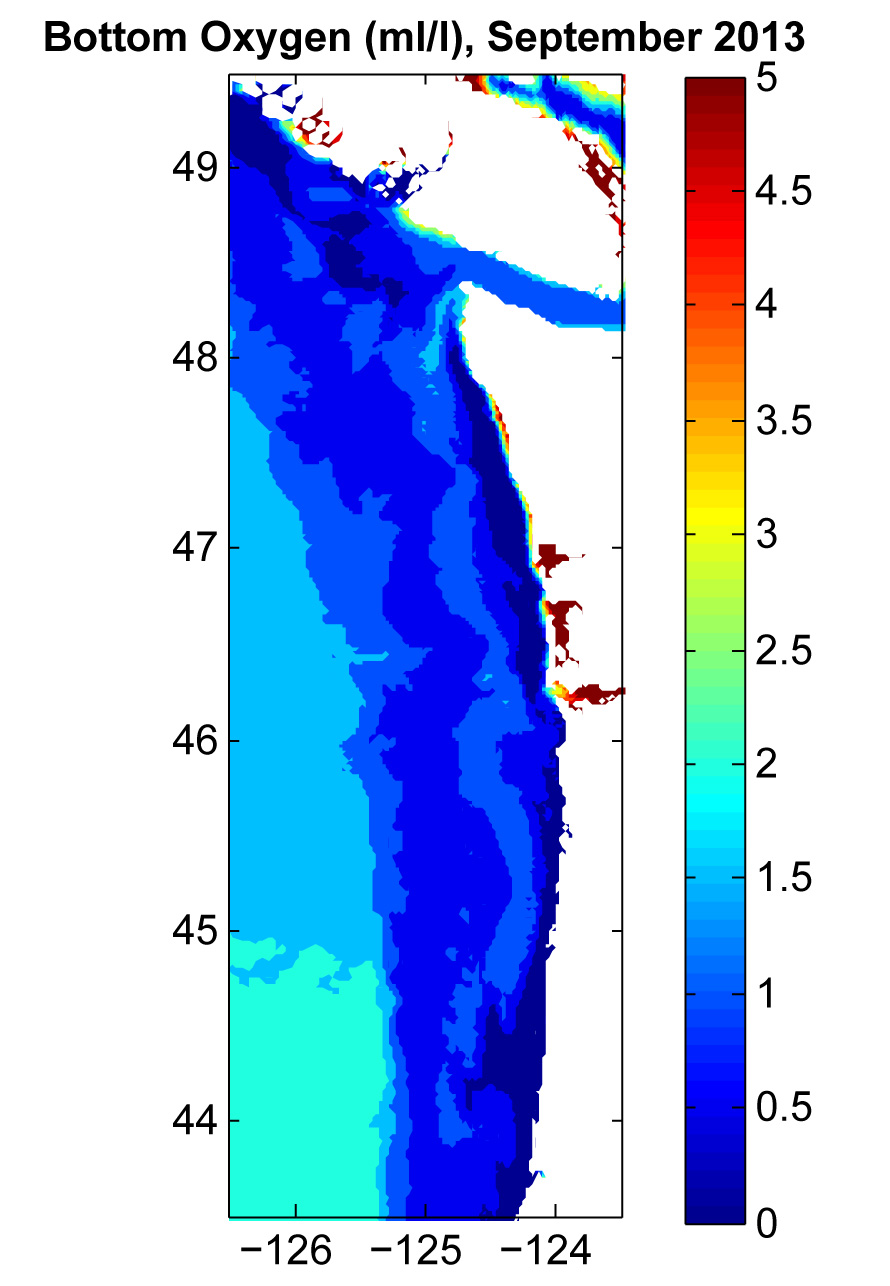

In January, when the prototype was launched, it predicted unusually low oxygen this summer off the Olympic coast. People scoffed. But when an unusual low-oxygen patch developed off the Washington coast in July, some skeptics began to take the tool more seriously. The new tool predicts that low-oxygen trend will continue, and worsen, in coming months.

“We’re taking the global climate model simulations and applying them to our coastal waters,” saidNick Bond, a UW research meteorologist. “What’s cutting edge is how the tool connects the ocean chemistry and biology.”

Bond’s research typically involves predicting ocean conditions decades in advance. But as Washington’s state climatologist he distributes quarterly forecasts of the weather. With this project he decided to combine the two, taking a seasonal approach to marine forecasts.

The National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration funded the project to create the tool and publish the two initial forecasts.

“Simply knowing if things are likely to get better, or worse, or stay the same, would be really useful,” said collaborator Phil Levin, a biologist at NOAA’s Northwest Fisheries Science Center.

Early warning of negative trends, for example, could help to set quotas.

“Once you overharvest, a lot of regulations kick in,” Levin said. “By avoiding overfishing you don’t get penalized, you keep the stock healthier and you’re able to maintain fishing at a sustainable level.”

The tool is named the JISAO Seasonal Coastal Ocean Prediction of the Ecosystem, which the scientist dubbed J-SCOPE. It’s still in its testing stage. It remains to be seen whether the low-oxygen prediction was just beginner’s luck or is proof the tool can predict where strong phytoplankton blooms will end up causing low-oxygen conditions, Siedlecki said.

The tool is named the JISAO Seasonal Coastal Ocean Prediction of the Ecosystem, which the scientist dubbed J-SCOPE. It’s still in its testing stage. It remains to be seen whether the low-oxygen prediction was just beginner’s luck or is proof the tool can predict where strong phytoplankton blooms will end up causing low-oxygen conditions, Siedlecki said.

The tool uses global climate models that can predict elements of the weather up to nine months in advance. It feeds those results into a regional coastal ocean model developed by the UW Coastal Modeling Group that simulates the intricate subsea canyons, shelf breaks and river plumes of the Pacific Northwest coastline. Siedlecki added a new UW oxygen model that calculates where currents and chemistry promote the growth of marine plants, or phytoplankton, and where those plants will decompose and, in turn, affect oxygen levels and other properties of the ocean water.

The end product is a nine-month forecast for Washington and Oregon sea surface temperatures, oxygen at various depths, acidity, and chlorophyll, a measure of the marine plants that feed most fish. Coming this fall are sardine habitat maps. Eventually researchers would like to publish forecasts specific to other fish, such as tuna and salmon.

The researchers fine-tuned their model by comparing results for past seasons with actual measurements collected by theNorthwest Association of Networked Ocean Observing Systems, or NANOOS. The UW-based association is hosting the forecasts as a forward-looking complement to its growing archive of Pacific Northwest ocean observations.

Siedlecki’s analyses suggest the new tool is able to predict elements of the ocean ecosystem up to six months in advance.

Researchers will present the project this year to the Pacific Fishery Management Council, the regulatory body for West Coast fisheries, and will work with NANOOS to reach tribal, state, and local fisheries managers.

If the forecasts prove reliable, they could eventually be part of a new management approach that requires knowing and predicting how different parts of the ocean ecosystem interact.

“The climate predictions have gotten to the point where they have six-month predictability globally, and the physics of the regional model and observational network are at the point where we’re able to do this project,” Siedlecki said.

Source: University of Washington