By Micheal Rios, Tulalip News

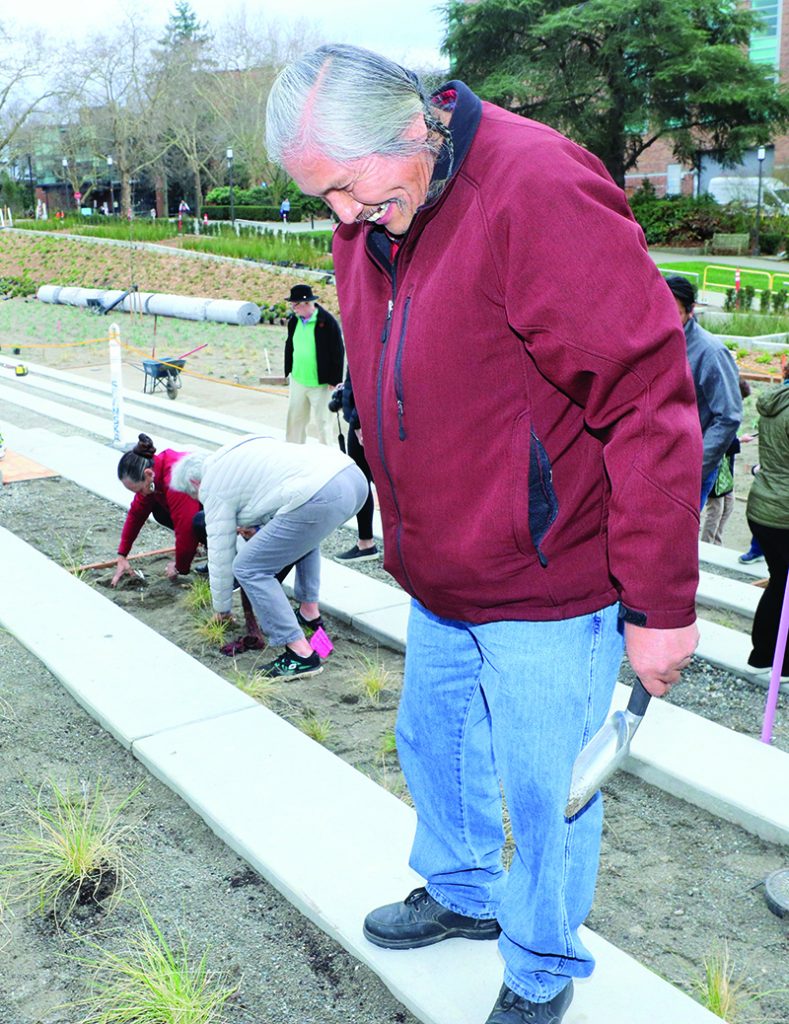

Tribal elders led a planting ceremony that included University of Washington students, faculty, and visitors on the afternoon of December 3. In the spirit of growing partnerships and sharing the importance of land cultivation, the memorable gathering occurred near the new Burke Museum’s entrance. Home to a future Camas meadow.

“This garden here will be a witness and teacher to something that is very important and sacred to all people, but especially to this land,” said Wanapum tribal elder Rex Buck. “The land has longed for these foods to come back and call it home. And so this is our way, the Burke’s way and the community’s way to recognize this planting as important. It represents a teaching for our children to maintain something sacred in a good way.”

After receiving proper instruction on how to plant budding Camas bulbs, all those in attendance were encouraged to plant multiple bulbs that will transform into stunning purple-blue flowers in a few short seasons. Once fully bloomed, visitors to the University of Washington and Burke Museum will find themselves walking by a Camas meadow, as were once in great abundance in the area prior to colonization.

A utilitarian plant, food source and medicine, the multi-purpose Camas was and continues to be one of the most important root foods of Indigenous peoples in western North American. Except for choice varieties of dried salmon, no other food item was more widely traded. People traveled great distances to harvest the bulbs and there is some suggestion that plants were dispersed beyond their range by transplanting.*

The part of the plant most revered is actually the bulb. Traditionally, Camas bulbs were pit-cooked for 24-36 hours, which was necessary for the inulin in Camas to convert to fructose. The sweetness of cooked Camas gave it utility as a sweetener and enhancer of other foods, making it highly valuable for trading purposes. The plants stalks and leaves were used for making mattresses. Additionally, Coast Salish tribes used Camas as a cough medicine by boiling it down, straining the juice, and then mixing with honey.

“Camas is medicine that our people have known and understood for thousands and thousands of years,” explained Cedar Moon Woman, Connie McCloud, cultural director of Puyallup Tribe. “The Creator put this plant here for us to nourish our bodies as food and to heal our bodies as medicine. The land knew this medicine would return here today so it would be an educator for our children. If our future generations do not understand their relationship to the Mother Earth, to the trees and to the plants, then they cannot be the protectors she desperately needs.”

The long-awaited planting ceremony and gardening activities have been years in the making, since design plans for the new Burke were first being drawn up. Ultimately, the museum’s surroundings will feature some 80,000 native plants of 60 different species representing different parts of Washington State, ones genetically tied to the region. The spring bloom of purple-blue flowers should be spectacular. This is yet another way to bring the region’s natural history to the public.

“In planning for the new Burke, many of us advocated for having the whole grounds of the museum be a garden to represent the plants that are native to the Pacific Northwest and of value to the Indigenous people who live here,” explained Dr. Richard Olmstead, UW professor and Burke curator. “When Meriwether Lewis came west with the Lewis & Clark Expedition, he was the first European to collect this plant and provide it to western science. In providing a name for it, the Latin name Camassia quamash brings together the two words he had learned in phonetic English that represented the Native American names for this plant species.”

In time, the Camas bulbs planted by environmentally-conscious citizens of all ages and professions will blossom into a sweeping meadow alongside the Burke Museum. The meadow will evoke thoughts of wild prairie lands that once covered much of Washington, during a time when Indigenous people were sole caretakers and Camas was widely known not simply as a flower or plant, but as life giving food and medicine.

*source: https://plants.usda.gov/plantguide/pdf/cs_caquq.pdf