Two dozen years after her death, Harriette Shelton Dover continues to be a guide and an inspiration far beyond the Tulalip reservation.

What it must have been like to sit and have a chat with her … to be fortunate enough to hear her share the stories that elders had shared with her about the times before the treaties … to learn about what she had witnessed on the road from the assimilation era to the Tulalip Tribes’ economic and political resurgence.

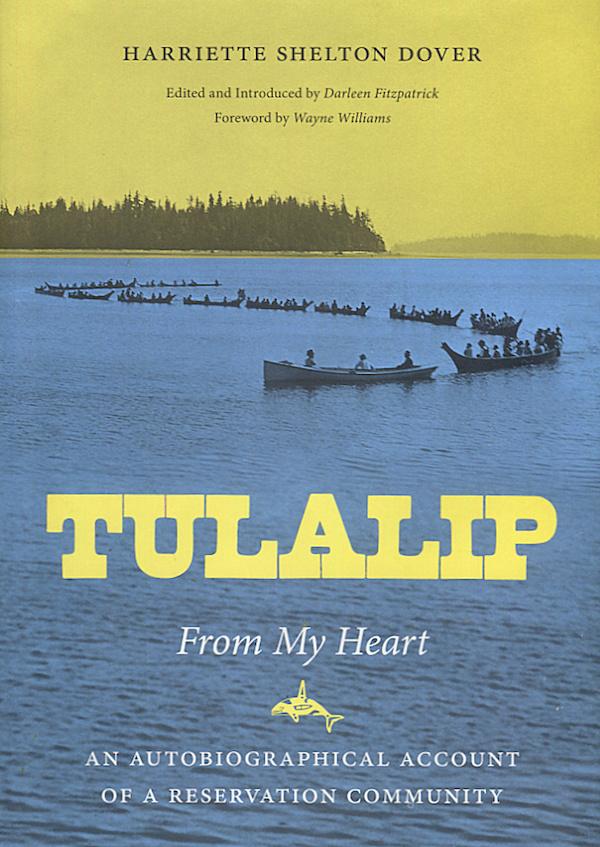

Dover, who walked on in 1991 at age 86, continues to pass on the teachings of her elders and bear her own witness in an inspiring, no-holds-barred oral history, Tulalip From My Heart: An Autobiographical Account of a Reservation Community (University of Washington Press, 2013). This 308-page book is the product of a series of tape-recorded interviews between Dover and anthropologist Darleen A. Fitzpatrick, conducted once a week from 1981–83. Fitzpatrick is also the author of We Are Cowlitz: Traditional and Emergent Ethnicity, University Press of America, 2004.

Dover had a unique position from which to witness the struggles and survival of her people after the signing of the Treaty of Point Elliott of 1855. She was born in 1904, 49 years after the signing of the treaty; her granduncle, Steh-shail, was a treaty signer, and her paternal grandfather was present at the signing. Her father, William Shelton (1868–1938), was a hereditary chief of the Snohomish and spent much of his life trying to bridge the divide between Coast Salish people and whites. Her mother, Ruth Sehome, was the daughter of Sehome, a leader of the S’Klallam people.

Dover grew up listening to elders’ firsthand accounts of the hardships her people experienced after moving from their villages to the reservation on Tulalip Bay: inadequate food and water, harsh economic conditions, religious persecution, and the outlawing of potlatches and traditional ceremonies. She experienced the hardships and prejudices of the assimilation era and spent 10 months of every year for 10 years in an Indian boarding school, where children were treated harshly and loving kindness was rare.

But Dover was unyielding in retaining her Coast Salish identity—she was Hiahl-tsa, the daughter of Wha-cah-dub and Siastenu. She was unyielding in her sense of justice. She knew her people’s history, she knew what the treaty said, and she knew her people never gave up their right to continue their traditional lifeways, their right to govern themselves, their right to coexist.

“We have been here for a long, long time,” she says near the book’s close. “We have always been here.”

She also believed, as did her father, that people from different cultures could learn to understand each other and look beyond their differences. Dover, who had witnessed troubled marriages between Native women and non-Indian men, was married first to a S’Klallam/Tsimshian man, then later to a white man.

In her book, Dover tells of treaty time, settling on the reservation, finding work in the early days, the first memories of white people, the elders’ teachings, the boarding school experience, treaty rights, public school (she graduated from Everett High School in 1926), political and social conditions, and her people’s legacy.

She was there when her father built the first traditional longhouse of the new era in 1913, and was present at the first Treaty Day commemoration in January 1914. In 1927 she assisted her father in the case brought before the U.S. Court of Claims, seeking proper payment for lands ceded in the treaty.

She was elected to the Tulalip Tribes Board of Directors in 1939 and later served as chairwoman; she also served as postmaster of the U.S. Post Office at Tulalip. She was, like her father, a bridge between the Native and non-Native communities—she was a member of the Everett Business and Professional Women’s Club and Everett Church Women United, wrote as a periodic contributor to the Seattle Post-Intelligencerand served on the Marysville School Board.

Dover shared information about cultural items and her people’s history with anthropologists, and worked with academic linguists to help preserve her people’s language. In the 1970s, she helped revive the ancient First Salmon Ceremony, honoring the year’s first salmon that is caught. She testified in the 1974 federal court case of United States vs. Washington, which affirmed her people’s treaty right to harvest salmon “at all usual and accustomed grounds and stations.” She earned a degree at Everett Community College while in her 70s.

In her book, Dover still teaches about standing up for what is right, about living a life of honor, love, resilience and respect.

“For many people she is still a personal guide, and the memory of her courage and commitment to the well-being of her people is still a force for good in the community,” one book reviewer wrote of Dover. “There is information here that you will find nowhere else about [Tulalip] in the early years of the 20th century.”

Read more at http://indiancountrytodaymedianetwork.com/2015/06/07/heart-tulalip-history-and-memoir-walk-back-time-160622