Tag: Tribes

Proponents fight for change so Alaska Natives covered by VAWA

Complicated history excludes Alaska Native women from Violence Against Women Act

By: Kayla Gahagan, Aljazeera America

Opponents of the reauthorization of a federal law passed last year say it has created a dangerous situation for Alaskan domestic violence victims and are urging lawmakers to support a repeal.

Proponents of the original 1994 Violence Against Women Act say it was signed into law with the purpose of providing more protection for domestic violence victims and keeping victims safe by requiring that a victim’s protection order be recognized and enforced in all state, tribal and territorial jurisdictions in the U.S.

According to the White House, the VAWA has made a difference, saying that intimate partner violence declined by 67 percent from 1993 to 2010, more victims now report domestic violence, more arrests have been made and all states impose criminal sanctions for violating a civil protection order.

Last year the law was reauthorized, clarifying a court decision that ruled on a case involving civil jurisdiction for non–tribal members and amending the law to recognize tribal civil jurisdiction to issue and enforce protection orders “involving any person,” including non-Natives.

But almost all Alaska tribes were excluded from the amendment, with only the Metlakatla Indian community from Alaska included under the 2013 law. The rest of Alaska remains under the old law.

The change has created confusion, opponents say, particularly in cases when there is a 911 call about enforcing a protective order.

“The trooper is waiting, because he’s not sure who has jurisdiction,” said David Voluck, a tribal court judge for the Central Council of Tlingit and Haida Indian Tribes of Alaska. “We need to get rid of those exceptions that create confusion.”

An ongoing debate

The reauthorization highlighted an ongoing debate about Native communities and tribal courts’ and governments’ jurisdiction, particularly in cases of policing and justice.

The reauthorization made sense, according to Alaska Attorney General Michael Geraghty, who noted that Alaska has always been treated differently because of the 1971 Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act. In exchange for 40 million acres of land and about $1 billion, he said, tribes forfeited reservations and the notion of Indian country to form Native corporations.

He said the state needs to find better ways to collaborate with institutions in small communities to provide better protection and justice but disagrees with giving pockets of tribal authority throughout Alaska.

“We do have an issue with violence and domestic violence,” he said. “We have a challenge in providing safety.”

But Geraghty said he has never heard of a situation when a victim was in danger because of confusion over jurisdiction.

“There’s nothing in the act that expands or retracts the jurisdiction of tribal courts,” he said. “If tribal courts had jurisdiction before, they do now. Troopers are not lawyers. If they are faced with a situation, they are going to protect the public. These concerns are overblown.”

‘A cloud over Alaska’

Lloyd Miller, an attorney who works on Indian rights and tribal jurisdiction litigation, disagrees and said things did change with the 2013 reauthorization.

“What he’s saying is that an Alaska village only has the authority to issue a protective order if that man is a member of the tribe. They can’t if he’s from the neighboring tribe,” he said. “Why would we not want to have Alaska villages have all the tools to protect women from domestic violence?”

Voluck agreed. “Does it really matter if a woman is hit in a mall somewhere or the south corner of where the tribe lives?” he said.

Opponents of the Alaska exemption recently urged a task force convened by Attorney General Eric Holder to study the effects of violence on Native American children to support the repeal of Section 910 of the law.

“VAWA creates a cloud over Alaska, and the last thing women and children need is a delay in an emergency,” said Voluck. “A matter of minutes can mean life or death. It’s unequal protection under the law for a very vulnerable part of the population.”

Lack of law enforcement

Voluck was one of a number of experts who testified last month before the Task Force on American Indian and Alaska Native Children Exposed to Violence about the special circumstances surrounding Alaska Native domestic violence, including geography, a lack of law enforcement and difficulty for victims to travel to safety.

Experts attested to a number of facts, including that Native American and Alaska Native women are 2.5 times as likely to be raped or sexually assaulted than other American women. About 140 villages have no state law enforcement. Eighty have absolutely no law enforcement. One-third of Alaska communities do not have road access.

It’s a serious issue for communities, said Valerie Davidson, a task force member who lives in Alaska. “Even if you only have 300 people, you still need law enforcement,” she said.

The debate continues, this time in Congress as the Senate Indian Affairs Committee works on legislation, which includes a provision repealing Section 910 of the 2013 reauthorization. Geraghty and the governor oppose a repeal, but the U.S. attorney general’s office has voiced its support.

Associate U.S. Attorney General Tony West attended the Alaska task force hearing and said arguments about the scope of authority of Alaska Native villages and tribes shouldn’t get in the way of protecting Native children from harm.

“If there are steps we can take that will help move the needle in the direction for victims, we need to do it,” he said. “When a tribal court issues an order, the state ought to enforce it. If not, the orders are worth nothing more than the paper they’re written on.”

More than just symbolic

Repealing the law won’t resolve the multilayered issues of jurisdiction, but it would be a step in the right direction, West added.

“It is more than just symbolic,” he said. “Repeal of Section 910 is an important step that can help protect Alaska Native victims of that violence and, significantly, the children who often witness it, and it can send a message that tribal authority and tribal sovereignty matters, that the civil protection orders tribal courts issue ought to be respected and enforced.”

The Task Force on American Indian and Alaska Native Children Exposed to Violence will make a recommendation to Holder by late October.

“Alaska is frozen in time,” Voluck said. “Why in the world would you hold the worst state when it comes to domestic violence in the old law? Forty-nine other states have figured out how to work with their tribal courts. Let’s work together. People are getting hurt and dying. That’s why I’m upset.”

Critics say proposed rules on fish consumption insufficient

Tribal leaders are skeptical of a proposal by Gov. Jay Inslee to set new water-quality standards.

By Lynda V. Mapes, Seattle Times, July 21, 2014

Some tribal leaders and environmental groups say a water-pollution cleanup plan proposed by Gov. Jay Inslee this month is unacceptable because while it tightens the standards on some chemicals discharged to state waters, it keeps the status quo for others.

Inslee is drafting a two-part initiative to update state water-quality standards, to more accurately reflect how much fish people eat, and to propose legislation to attack water pollution at its source. The fish-consumption standards have the effect of setting levels for pollutants in water: The more fish people are assumed to eat, the lower the amount of pollution allowed.

Inslee decided that lowering some standards wouldn’t create a big-enough benefit to human health to justify the economic risk for businesses, said Kelly Susewind, water-quality program manager for the state Department of Ecology.

“The realistic gains on the ground didn’t warrant that concern and disincentive to invest in our state,” Susewind said.

That’s because the rules regulate state permits for dischargers, such as industrial manufacturers and wastewater-treatment plants — but that isn’t where most of the pollution is coming from.

Setting tougher standards for some pollutants would also result in levels too low to detect or manage with existing technology — but would create a regulatory expectation that could cloud future business investment, Susewind said.

“The concern is that we set in motion a chain of events where it is inevitable they can’t comply. If they are worried they will cease to invest in 30 years, they are not going to invest today; that is the long-term picture that caused the uncertainty.”

In the case of PCBs — polychlorinated biphenyls, industrial chemicals used as coolants, insulating materials, and lubricants in electric equipment — setting a limit below the existing limit of 170 parts per quadrillion wouldn’t improve people’s health, Susewind said. That’s because most PCBs are entering waterways from other sources, including runoff. “It is not the most effective place, to put the pinch on dischargers,” Susewind said.

The problem is that the Clean Water Act, under which the standards are issued, doesn’t reach beyond so-called point sources: pollution in water discharged from pipes by industries and others regulated by Ecology and the federal Environmental Protection Agency (EPA).

“A lot of our challenge is finding ourselves with only one tool,” said Carol Kraege, who leads toxics reduction at Ecology. “Getting toxics out of our water with just the Clean Water Act is not enough.”

To gain new tools to clean up state waters, Inslee has asked Ecology to put together legislation to expand its authority to ban certain chemicals, to keep them from getting in the water in the first place. The legislation, which is still being drafted, is intended to address so-called non-point sources of pollution.

The governor has said he won’t submit a final water-quality rule to the EPA for approval until after the legislature acts.

Christie True, director of King County Natural Resources and Parks, which runs the county’s wastewater-treatment plants, said she was encouraged by the governor’s approach. “We have to be focused on outcomes,” True said.

“The thing I was really happy about was he said we can’t just rely on regulating the same old sources if we want to improve water quality. I know it is going to be very challenging to take these issues to the Legislature, but that is where we need to head to have a better outcome.”

The debate now under way arose from the state’s need to update the water-quality standards that address health effects for humans from eating fish. The state’s rules today assume a level of consumption so low — 6.5 grams a day, really just a bite — that it is widely understood to be inadequately protective, especially for tribes and others who eat a lot of fish from local waters.

The standard also incorporates an incremental increase in cancer risk in that level of consumption.

Inslee has proposed greatly increasing the fish-consumption standard in the new rule, to 175 grams per day, a little less than a standard dinner serving. But he also upped the cancer risk, from 1 in 1 million under current law, to 1 in 100,000 in the new standard. That was to avoid imposing tighter standards for some pollutants.

That isn’t good enough for tribal leaders who say they want tougher protection now — for all pollutants, not just some. “Holding the line isn’t good enough,” said Dianne Barton, water-quality coordinator for the Columbia River Intertribal Fish Commission.

Counting on the Legislature to grant new authority to Ecology and money to back it up is also a shaky proposition, some said. “That is a big gamble,” said Chris Wilke, executive director of Puget Soundkeeper, a nonprofit environmental group that sued the EPA to force Washington to update its standards. Delay, meanwhile, “is more business as usual,” Wilke said.

Brian Cladoosby, chairman of the Association of Washington Tribes and the Swinomish Indian Tribal Community, said tribes are going to take their case directly to the feds both at Region 10 EPA and in the EPA administrator’s office in Washington, D.C., and insist no change be made in the cancer risk.

“In our minds, the bar hasn’t moved that much,” Cladoosby said. “It took 100 years to screw up the Salish Sea; hopefully, it won’t take another 100 years to clean it up. But we have to start somewhere.”

Studio looks for Native American stars

By Daily Times staff, The Daily Times

FARMINGTON — TBA, a Los Angeles-based network, is hosting a casting call today and Saturday for a reality TV “docuseries” about a subculture of Native American youth.

The studio is looking for people between 18 and 28 years old who are interested in a medical career, environmentalism, leadership or similar programs. The people must be outgoing and not camera shy.

Auditions are from 4 to 8 p.m. today and 11 a.m. to 3 p.m. Saturday at Comfort Inn Suites, 1951 Cortland Drive in Farmington.

The show will focus on young Native Americans who leave the reservations, tribes, cultures and ways of life to pursue life in a city.

The studio is looking for a few people who are willing to leave everything behind to pursue their “big dream.”

According to a press release, the show will look at how their leaving might cause disruption to their communities and what they are willing to endure to achieve a dream bigger than themselves. If they succeed, their work will help many others including their tribe.

TBA is comparing the new series to Breaking Amish.

For more information, call or text 818-299-0949

Obama Allocates $10 Million for Tribal Climate Change Adaptation

President Barack Obama on July 16 released another set of climate-change-resilience guidelines, this batch geared specifically toward tribes, and announced the allocation of $10 million to help tribes cope with climate change.

The allocation was one of a number of measures announced at the final meeting of the White House State, Local, and Tribal Leaders Task Force on Climate Preparedness and Resilience, created by Obama last fall. Karen Diver, chairwoman of the Fond du Lac Band of Lake Superior Chippewa in Minnesota, and Reggie Joule, mayor of the Northwest Arctic Borough in Alaska, were the tribal officials designated to serve on the task force.

RELATED: A Chat With Fond du Lac’s Karen Diver, Presidential Climate Change Task Force

The money will fund the development of resource management methods, climate-resilience planning, and youth education and empowerment. Climate adaptation grants will also be awarded for the development of climate-adaptation training programs, assessment of vulnerability, monitoring and other aspects of learning about the effects of climate change. Adaptation planning sessions will be offered, and tribal outreach will be funded with the money as well, Interior said. Administration officials said such measures are sorely needed.

RELATED: 9 Tribal Nations Taking a Direct Hit From Climate Change

“From the Everglades to the Great Lakes to Alaska and everywhere in between, climate change is a leading threat to natural and cultural resources across America, and tribal communities are often the hardest hit by severe weather events such as droughts, floods and wildfires,” said Secretary of the Interior Sally Jewell, chair of the White House Council on Native American Affairs, in a statement. “Building on the President’s commitment to tribal leaders, the partnership announced today will help tribal nations prepare for and adapt to the impacts of climate change on their land and natural resources.”

Obama has been highlighting the effects of climate change on Native peoples in his efforts to construct a plan for dealing with the inevitable changes.

RELATED: Obama Taps Tribes to Assist in Adapting to Climate Change

“Impacts of climate change are increasingly evident for American Indian and Alaska Native communities and, in some cases, threaten the ability of tribal nations to carry on their cultural traditions and beliefs,” said Assistant Secretary of Indian Affairs Kevin Washburn. “We have heard directly from tribes about climate change and how it dramatically affects their communities, many of which face extreme poverty as well as economic development and infrastructure challenges. These impacts test their ability to protect and preserve their land and water for future generations. We are committed to providing the means and measures to help tribes in their efforts to protect and mitigate the effects of climate change on their land and natural resources.”

The Interior Department will also team up with the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) to create a subgroup on climate change under the White House Council on Native American Affairs, the DOI said. This cooperation between Jewell and EPA Administrator Gina McCarthy will entail working with tribes to pool data and information on climate change effects that are directly relevant to issues faced by American Indians and Alaska Natives. Traditional and ecological knowledge will be a cornerstone of the initiative.

“Tribes are at the forefront of many climate issues, so we are excited to work in a more cross-cutting way to help address tribal climate needs,” said McCarthy in the statement. “We’ve heard from tribal leaders loud and clear: when the federal family combines its efforts, we get better results—and nowhere are these results needed more than in the fight against climate change.”

Read more at http://indiancountrytodaymedianetwork.com/2014/07/16/obama-allocates-10-million-tribal-climate-change-adaptation-155890

Video: National Climate Assessment Focuses on Natives Bearing the Brunt

As the effects of climate change become more and more pronounced and better understood, the concerns of Indigenous Peoples are coming more and more to the fore. Conventional science is beginning to understand not only that they suffer inordinately from the phenomenon, but also that their traditional knowledge could hold some keys for adaptation, if not mitigation.

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Climate Change Assessment in May highlighted the effects on Indigenous Peoples, including those from the Pacific Islands and the Caribbean. In concert with that the authors made a video that lays out some of these challenges and how they are interconnected. Below, an interview with T.M. Bull Bennett, a convening lead author on the National Climate Assessment’s Indigenous Peoples chapter.

RELATED: Obama’s Climate Change Report Lays Out Dire Scenario, Highlights Effects on Natives

“We’re starting to see a change in how we interpret the environment around us,” Bennett says below. Indigenous populations, he adds, are “on the short end of the stick.”

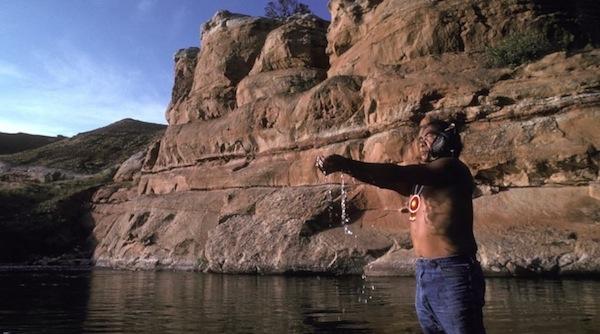

Saving the sea that feeds us

Tulalip tribal member Tony Hatch presents the first salmon of the fishing season during a Salmon Ceremony on the Tulalip Reservation in 2004. The traditional ceremony honors the first salmon to be caught with the hope that the fishing season will be plentiful. Following a feast, the bones of the salmon are returned to the water so that the honored fish will speak highly of the tribe.

By Les Parks, Source: The Herald

Puget Sound is one of the iconic wonders of the world and defines who we are, not only as tribes, but all residents of Western Washington.

This great body of water was still being formed by receding glaciers when the tribes arrived, and we have lived off her abundant natural resources ever since. Over thousands of years our beautiful and unique inland sea has become a complex ecosystem, supporting not only an abundance of sea life, but also mixing with freshwater resources at the mouths of our great rivers, providing a consistent and plentiful food source for us humans.

This natural resource wealth has influenced every part of our tribal traditions. Stories of the great salmon runs have been carried down through the generations, and they tell us these waters once rippled with silver, as salmon arrived home after several years out to sea. The clams, crab and mussels were also abundant, and along with berries, roots and the plants we harvested, our traditional diet was, and continues to be, sacred to us.

The old Indians used to say, “When the tide is out, the table is set!”

For more than 200 years the descendants of the settlers, and now peoples from around the globe, have called the Puget Sound home. Like the tribes, they have lived off her rich resources, appreciated her great beauty and passed laws to protect her from exploitation.

Today, however, the health of Puget Sound is failing fast. In recent years it has lost 20 percent, or more, of the plankton that makes up the base of our food web. Everything above plankton in the food chain is also affected and is showing signs of great stress. The loss of plankton is beyond comprehension and is the single greatest barometer of what is happening to the waters we have all largely taken for granted.

It is time the citizens of Washington, and in particular citizens of Puget Sound, act on this information. With plankton gone, it means every animal up the food chain pays the price, including us.

Mark my words: Puget Sound is dying! Finding whales dying from natural causes is expected. Finding whales that are emaciated and starving is alarming and will become a common scenario if we do not address the problem quickly. But what is happening; why are plankton dying? We are only beginning to understand the complex interactions between warming ocean waters, how they affect the state’s inland sea, and how human activities play into this alarming situation.

Toxins in the food chain are devastating from the bottom all the way up. Recent evidence suggests that nutrient pollution, such as nitrogen and phosphorus from wastewater treatment plants, septic systems, residential homes, agriculture and other sources, are significantly disrupting the food web in Puget Sound. We cannot continue to ignore the fact that the sound is the baseline of our livelihoods and that we humans are only as healthy as our environment.

The great waters and rivers of the Salish Sea have existed since the last ice age (13,000 years ago) and with the melting of the ice the Puget Sound was born. Mother Nature has created this beautiful place we call home, and in less than 200 years, and largely within the last 100 years, we have managed to undo what Mother Nature provided us.

How many more years will it take to entirely wipe out sea life in Puget Sound? Can she sustain the barrage of pollutants that are killing the plankton for another 50 years? Do we have another 25 years to act before reaching the tipping point, or have we already arrived? Our window of opportunity to heal her is closing. It is our duty to do all that we can to improve her health and time is not on our side.

The Tulalip Tribes have collaborated with governments, nonprofits, and other entities on a variety of habitat restoration projects, on and off reservation, and we continue to lobby for the protection of Puget Sound. One project that we feel very proud to be a part of is Qualco Energy. Partnering with farmers and environment groups in the Snohomish River basin we have worked together to build an anaerobic digester, which channels cow manure away from streams and fresh groundwater sources by converting it to electricity before it is sold to the electricity grid. It is an example of the type of collaboration it will take to restore the health of our Sound.

Gov. Jay Inslee announced his proposal this week to address the issue of fish consumption that has large implications for our health and water quality standards. Gov. Inslee’s proposal begins to address Puget Sound’s health but not to the level that we had hoped. While the proposed rate of fish consumption is significantly higher, his proposal also increases the risk of cancer deaths by some toxins. The governor’s proposal strengthens water quality with one hand, but weakens it with the other. The net effect seems to be a very modest change for some chemicals, and no change at all for others. It also represents yet another delay on committing to the health of the Puget Sound, and to the health of those who depend on its resources.

There are no winners in the governor’s announcement. We want to be able to encourage our people to eat more fish and shellfish, as it sustained them well for many generations, and forms the basis of our shared ways of life. We remain hopeful that the court of public opinion will convince the governor to reconsider his proposal so that when the tide is out it is safe to eat at the table.

Les Parks is the vice chairman of the Tulalip Tribes.

Tribe Helps Elk Herds Reclaim Their Home After Fire

The Cachil Dehe Band of Wintun Indians hopes Tule elk will return home to their reservation land. The tribe received $89,200 in grant funding from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, through the organization’s competitive Tribal Wildlife Grants Program, to restore elk habitat on its 7,000-acre property in Colusa County, California.

Roughly three herds are roaming about three to four miles outside the tribe’s ranch currently, but their range expansion has been limited by chamise, the native evergreen shrub that formerly grew extensively on the ranch before a 2012 fire burned it out. “Now that the fire’s gone through, it may open up the [elk’s] migration patterns,” Casey Stafford, director of land management for the Cortina Ranch, told newsreview.com. “We’re just going to try to get them a new place to call home.”

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service awarded 25 grants nationwide to federally recognized tribes in 15 states, including five in California, to fund a wide range of fish and wildlife conservation projects.

“Tribal nations share our conservation challenges in the United States,” said Service Director Dan Ashe. “The Tribal Wildlife Grants Program creates opportunities for tribes to build conservation capacity and for us to work together in a variety of ways, including species restoration, fish passage, protection of migratory birds and efforts to cope with the long-term effects of a changing climate.”

Tribes have received more than $64 million through the Tribal Wildlife Grants Program since 2003, providing support for more than 380 conservation projects administered by participating federally recognized tribes. These grants provide technical and financial assistance for development and implementation of projects that benefit fish and wildlife resources, including nongame species and their habitats.

The grants provide tribes opportunities to develop increased management capacity, improve and enhance relationships with partners (including state agencies), address cultural and environmental priorities and heighten tribal students’ interest in fisheries, wildlife and related fields of study. A number of grants have been awarded to support recovery efforts for threatened and endangered species.

The grants are provided exclusively to federally recognized tribal governments and are made possible under the 2002 Related Agencies Appropriations Act through the State and Tribal Wildlife Grants Program. Proposals for the 2015 grant cycle are due Sept. 2, 2014.

For information about projects and the Tribal Wildlife Grants application process, visit http://www.fws.gov/nativeamerican/grants.html.

FY 2014 Tribal Wildlife Grants

ALASKA:

Native Village of Tazlina ($200,000)

Moose Browse Enhancement Project

Native Village of Tyonek (copy97,590)

Tyonek Area Watershed Action Plan

ARIZONA:

Tohono O’odham Nation ($200,000)

Engineering Design and Monitoring of State Route 86 Wildlife Connectivity Measures

CALIFORNIA:

Hoopa Valley Tribe (copy99,992)

Pacific Lamprey Passage Project

Pala Band of Mission Indians (copy89,645)

Tribal Habitat Conservation Plan Completion (Phase I and Phase II)

Santa Ynez Band of Chumash Indians (copy58,352)

Restoring and Enhancing Riparian Habitat on Chumash Tribal Lands

Cachil Dehe Band of Wintun Indians (copy89,200)

Cortina Ranch Tule Elk Restoration

FLORIDA:

Seminole Tribe of Florida ($200,000)

Seminole Tribe of Florida Tribal Wildlife Program

IDAHO:

Nez Perce Tribe ($200,000)

Restoration of Bighorn Sheep Populations and Habitats along the Salmon River, Idaho – Final Phase

MAINE:

Houlton Band of Maliseet Indians ($200,000)

Aquatic Habitat Restoration Program: Phase III – Fish Passage / Habitat Enhancement Project

Passamaquoddy Tribe – Pleasant Point Reservation (copy98,885)

Alewife Migration Behavior and Food Web Interactions in the St. Croix River and Estuary

MICHIGAN:

Nottawaseppi Huron Band of the Potawatomi (copy99,942)

Wildlife Habitat Assessment and Restoration Plan: Expansion and Implementation

MONTANA:

Northern Cheyenne Tribe (copy99,394)

Returning the Black-footed Ferret

Gros Ventre and Assiniboine Tribes of Fort Belknap Indian Community ($200,000)

Black-footed Ferret Reintroduction

NEW MEXICO:

Ohkay Owingeh (copy53,499)

Restoring Wet Meadow Habitats for Listed and Proposed Candidate Species at Ohkay Owingeh

Santa Ana Pueblo (copy99,998)

Monitoring Avian Community Response to Riparian Restoration along the Middle Rio Grande, Pueblo of Santa Ana

OKLAHOMA:

Osage Nation (copy85,511)

American Burying Beetle in the Osage Nation

OREGON:

The Klamath Tribes ($200,000)

Klamath Reservation Forest Habitat Restoration and Ecosystem Resiliency Project.

SOUTH CAROLINA:

Catawba Indian Nation (copy74,501)

Catawba Preserve Wildlife Enhancement

UTAH:

Confederated Tribes of the Goshute Reservation, Nevada and Utah (copy93,384)

Native Bonneville Cutthroat Trout Habitat Restoration Project

WASHINGTON:

Confederated Tribes and Bands of the Yakama Nation (copy99,803)

Yakama Nation Shrub-Steppe Species Restoration Project

Lower Elwha Klallam Tribe (copy99,616)

Mammalian and Avian Recolonization Ofde the Watered Reservoirs After Dam Decommissioning and Their Impact on Revegetation Management, Elwha Valley, WA

Swinomish Indian Tribal Community (copy20,000)

Restoring an Endemic Species to Native Tidelands: Olympia Oysters in Swinomish Pocket Estuaries

Tulalip Tribes of Washington ($99,822)

Monitoring Fish and Water Resources on the Tulalip Tribes Indian Reservation, Usual and Accustomed Lands, and Marine Waters of the Pacific Northwest

WISCONSIN:

Stockbridge-Munsee Community ($200,000)

Herptile Management and Habitat Restoration

Read more at http://indiancountrytodaymedianetwork.com/2014/07/03/tribe-helps-elk-herds-reclaim-their-home-after-fire-155636

Urban Indians Must Become Their Own Best Advocates

By Kyle Taylor Lucas, Guest Writer, Tulalip News

This is the final installment in a series exploring the largest demographic of American Indians and Alaska Natives–the Urban Indian. Through in-depth interviews, the series touches on some of the struggles, hopes, and aspirations of a largely invisible population.

The series introduction, Urban Relatives: Where do Our Relations Begin and End? provided a snapshot of urban Indian demographics and an overview of historical federal policies, which, according to the 2010 census, finds an astounding 78 percent of all American Indians/Alaska Natives residing off-reservation or outside of Native communities.

The second installment, The Tahoma Indian Center: Restoring and Sustaining the Dignity of Urban Indians, looked at a heroic urban Indian program that daily saves lives while operating on a shoestring. It recognized the Tahoma Indian Center and its director of more than 22 years, Joan Staples Baum. The story featured Tyrone Patkoski, an enrolled Tulalip member, known in the art world for his unique artistry.

Third in the series was “Tulalip Veteran Wesley J. Charles, Jr., True American: “Indian Born on the 4th of July.” It told the remarkable story of Tulalip elder and Viet Nam Veteran, Wesley J. Charles, Jr., and a life well lived.

The fourth story, Why Should Tulalip Tribal Members Care About the Affordable Care Act? focused upon the Affordable Care Act’s (ACA) benefits to tribal members, especially low-income urban Indians–the majority of whom have long barely survived without any health and dental care, whatsoever, and who stand to benefit most from the ACA.

More than 1 million American Indians and Alaska Natives, approximately two-thirds of the U.S. Indian population, now live away from their reservation or homelands. Their displacement is traceable to broken treaty promises, the Indian boarding school legacy, federal assimilation policies, forced relocation, termination, widespread non-Indian adoption policies, overall failed federal trust responsibilities of the past century, and inter-tribal competition for a piece of the pie.

In particular, federal “Relocation” policies of the 1950s and 1960s resulted in Indians leaving the reservation in droves. As part of its “Termination” and “Assimilation” policy, the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) offered grants and job training to entice Indians to leave for employment in urban areas. The promise of food on the table and a roof over the heads of one’s family appealed to hungry, impoverished, and un-housed Indians. Survival can be very seductive.

The intent of these federal policies was to remove Indians from the reservation in order to end federal trust responsibility. Unquestionably, the Diaspora’s cruel result is generations of Indians split from their sacred lands, people, culture, language, and traditions.

A largely untold story is that urban Indians were then and continue to be subject to devastating economic and social strife. For the most part, this invisible population receives a blind eye and a deaf ear from the federal government charged with its trust responsibility. In their opposition to urban Indian program funding, even tribal governments aid the injustice. As example, despite the fact that 78 percent of all American Indians/Alaska Natives reside off-reservation, only 1 percent of the federal Indian Health Service (IHS) budget is allocated to urban Indian health care. This did not happen by accident.

Moreover, despite a highly technological age, data to document the urban Indian condition is woefully lacking. Still relevant today are findings from a 1976 American Indian Policy Review Commission study. It found, “Government policies meant to assimilate if not eliminate, a portion of an entire race of people have created a large class of dissatisfied and disenfranchised people who, while being subject to the ills of urban America, have also been consistently denied services and equal protection guaranteed under the Constitution as well as by their rights as members of Federal Indian tribes.”

Regrettably, tribal government systems have also contributed to the struggle of their disenfranchised urban relatives. For example, at Tulalip, the Social Services Emergency Aid program, in place for countless years, disenfranchised its off-reservation tribal members by denial of access to emergency aid. When explanation was sought, none was forthcoming. Interview calls for this story were not returned. In essence, half of the Tulalip citizens were discriminated against. Already denied anything beyond basic health care at the tribal clinic, the added denial of emergency services was a bitter pill for many.

Tribal enrollment policies have also aligned to deny members identity. For example, the Tribes’ enrollment policy, based on residency rather than descendancy, has deprived generations of Indians rightful identity and affiliation with their people simply due to the accidental location of their birth and despite their descendancy and ancestor’s reservation allotments.

Even so, the urban Indian story is not all bleak. Many urban Indians strive to create and contribute to community with their urban Indian sisters and brothers, and to know their reservation families and communities. Some hope to return home one day when housing and employment opportunities align. Social media has also helped open avenues of communication and connection. Online tribal news outlets and opportunities for online language learning create new avenues of cultural affiliation and contribution. Add that the Affordable Care Act (ACA) is providing critical healthcare and dental services for urban Indians who have long gone without any care.

According to Rosalie “Rosie” Topaum of the Tulalip Tribes enrollment office, since December 2012, Tulalip enrollment numbers increased by 140 for a total enrollment of 4,422 with nearly half (2037) of all Tulalip citizens reside off the reservation. All but three of the new enrollments reside off reservation.

“Urban Indian” Stories

Photo/Dolce Vita Photo Boutique

Jaime Denise Singleton

Born in Everett, Jaime Denise Singleton, 28, Tulalip, spent her first year on the Tulalip reservation. Her father, Dennis Boon, and her grandmother, Helen Gobin-Henson are Tulalip. Her mother, Pam (Marquis) Phipps, is Aleut. The family relocated to Anchorage, Alaska following her parents divorce when she was three years old.

Eager to know her roots, Singleton returned to Tulalip at age twenty-one. “I hardly knew my Dad and didn’t know my family at all. Grandma Helen helped me find work as a temporary youth advocate in the Education Department.”

Despite its enormous economic success, lack of housing continues to be a challenge for the Tulalip Tribes. Many of those on the reservation reside with large extended family in one house. Although not unlike historic tribal communal living, today’s housing structures and work and school lifestyles are largely incompatible.

The lack of reservation housing is also a significant driver for the continuing large urban Indian population. Singleton said, “I lived at my grandma’s house for about six months. I didn’t sign onto the housing list because I knew people with children who had been on the list for years and still didn’t have a house. At the same time, my grandma also had my uncle, his girlfriend and children, my dad, and two other cousins living with her. It was very crowded.”

A common regret of many urban Indians is the isolation from tribal culture and community. “I didn’t know my family or my culture. That’s the worst disadvantage. One of my cousins showed me her regalia from dancing as a child and I felt I really missed out on things like that. Some of my cousins are weavers and they make the most beautiful things from cedar. I thought, I know how to crochet, so I could have learned how to do that.”

Unfortunately, many urban Indians also experience isolation from other Natives. “Because I am mixed and light-skinned, I feel like an outsider in the Native community. I am only one-eighth Tulalip. On my mom’s side, I am Aleut, but only one-sixteenth. My maternal great-grandma married a white man and they moved out of her home village and homesteaded on the Kenai Peninsula. Our family has slowly drifted apart. I know nothing about our culture on the Aleut side either.”

Asked about healthcare, Singleton said, “Up here in Anchorage, AK, they have an excellent Indian Hospital called Alaska Native Medical Center that I believe sets the standard for Indian healthcare.” Yet, she recalled growing up visiting the clinic in Kenai where “I always got the sense it was free when I was young, but as an adult I’ve witnessed a hard push to buy health insurance. I feel like the staff and nurses look down on you if you are not insured.”

The Singletons objected to the necessity to sign up for the ACA or “Oamacare” as it is commonly known. “We filed the exemption because my husband was upset about the Individual Mandate. He didn’t understand why, as Native Americans with Treaty Rights, we should be forced to purchase insurance for the healthcare that is supposed to be provided us. He is one-quarter Inupiaq, but is not an enrolled tribal member and not qualified for the lifelong exemption; neither is our daughter.”

Economically, Singleton’s husband, Steven, has had steady employment. “We’ve been married for almost five years and we have property in Georgia where Steven was born and raised.” Having moved to Alaska after the Recession, they’re excited to be relocating to Georgia to build a house.

Grateful for the tribal per capita program, Singleton added, “Because we decided I would stay at home to raise our daughter, Sequoia, the per capita together with babysitting has really helped.” She is grateful, too, for the annual bonus, which has allowed them to “bank” for critical needs, such as their move to Georgia this summer.

On what Tulalip does right, Singleton said, “Our tribe values culture and respects traditions for ceremonies, gatherings, and funerals. It is wonderful to witness. I believe the Lushootseed language program should have greater emphasis because, like many native languages, it is on the verge of extinction. Our income from the Casinos puts us in a unique position to really “save” our language, and I would like to see that happen.”

To more equally serve the needs of off reservation members, Singleton suggested, “The tribe needs more housing! More than half of the homes in Housing Projects are left boarded up and abandoned while some of our membership lives with other family members, or homeless. I would like to see a program that opens up and turns the homes around faster and more homes available so our members have a place to live.”

“My family and extended family have always made me feel like I belong and that means a lot to me. They ask me things like, “When are you coming Home?” It makes me feel included because we know I was not raised there, yet it could still be my home,” said Singleton. She credited Facebook and social media for helping her to stay connected with her Tulalip family and community.

photo/Kyle Taylor Lucas

Myron Fryberg, Jr.

Myron Fryberg, Jr., 37, Tulalip, was adopted along with his sister, Joanne, by Myron Fryberg, Sr., and his wife, Mary. “I was adopted at the hospital. My mother is Tulalip and Puyallup, so I have ties with the Puyallup Tribe as well.” It was an open adoption allowing him to visit his birth mother, Deanne “Penny” Fryberg.

“My adopted mom, Mary, is full-blood and she knew all her relatives and family. I didn’t know myself. I was this kid who was given up by his dad. He was white,” said Fryberg who finally met his birth father’s family eight years ago. I learned that I’m Irish and Scottish, and a little French Canadian. The Irish are tribal too. The last name was O’Toole. I didn’t meet my dad, but I still talk to my brother.”

Residing off-reservation for the past five years, Fryberg said he was on the tribal housing waiting list, “but that’s a pretty slow process.” Caring for family at the time, he was forced to move “to town” [Marysville]. “I did a lot of praying and the idea came that maybe it was time to do something else. I was a janitor I asked, ‘do you want to turn 40 and realize that you didn’t do anything with your life?'”

Fryberg learned the Northwest Indian College (NWIC) offered a chemical dependency degree, so he returned to school. “I’ve now finished my third year and have a year to go,” said Fryberg, adding that he’s in the Tribal Governance and Business Management program.

Acknowledging that life has not been without challenges, Fryberg was candid about his struggles with alcohol. “I’ve been living in Bellingham for three years, going to school and staying busy. I had a rough patch at the beginning and I ended up getting a sponsor” who initiated him to service work. “We started working at the homeless shelter serving the homeless and I developed a sense of gratitude for what I had. Before that, I was hopeless about life,” said Fryberg who added, “I had lost my dad. I clung to him the most because I knew he was my relative. Me and my dad were really close. He always took me everywhere when I was a kid.”

Fryberg’s first tribal job was a blackjack dealer at age 19. “I did that for five years, but I didn’t like the structure there. I got clean and sober when I was 19, but I felt that I was treated less than by the tribe, so I went back to school and studied computers for three years.” Then, his friend committed suicide. “It put me back drinking for another four years. I finally quit drinking when I was 29.”

He again worked for Tulalip Tribes as a janitor at the health clinic and later at Tulalip Data Services. Yet, promises of raises were not forthcoming and Fryberg found the process for resolution of grievances unwieldy. He said that because he was supporting five children from family and a relationship, it was a turning point.

“When my dad passed I just didn’t want to be there. There was no chance for advancement or better pay and rather than go through the grievance process, I decided to return to school. I had seen the people that had an education made more money.”

Asked about disadvantages of living away from the reservation, Fryberg said, “There’s isolation. You get lonely. You don’t have your family, but Facebook has helped a lot.”

Unlike most urban Indians, healthcare has not been an issue for Fryberg. “We have non-profit health hospital in Bellingham. They don’t ask for paperwork.” He has also applied for Obamacare.

Fryberg said he is fortunate to live close to the reservation and a tribe with a similar culture. “The Lummi people at the college embraced me right away. I feel like they’ve kind of adopted me as one their own. It was good to see their culture is similar, but I always felt like Lummi was very close to their origins and held their culture close,” said Fryberg.

He noted having been immersed in his own culture at a young age. “We used to practice with the Jimicum family. We learned dance and songs and performed in Seattle. When my grandpa was ready to pass, my dad brought me to drum for him. My mom is Shaker, so we would go to shake on the weekends, and I helped in the kitchen,” said Fryberg. He has also studied Lushootseed.

Asked about his access to tribal social programs, Fryberg noted, “When I needed help, Tulalip said they couldn’t do because I was out of Snohomish County. There have been roadblocks there.”

He expressed gratitude for tribal per capita as having changed his life. “It has given me a chance to return to school and focus strictly on education.” He added, “The annual bonus has allowed me to put money aside to cover my rent when out of school over the summer.” It allows purchase of necessities he formerly had to forgo.

Fryberg conveyed some frustration with tribal government, “I think they are doing okay. Action seems to be a problem; presentation seems to be a problem. We try to cover up problems. We need to be more aware of where we came from. We need to change the whole philosophy. When we offer service to the people, we’re selling that service. Now, we’re offering a service that isn’t transparent. I tried to get the Board of Directors to hear my plea for non-profits, cooperatives, and getting people employed at Equal Square where there is no hierarchy. It’s a perfect example of assimilation. There’s a sense that oppression is all we know and that people don’t welcome change.”

Asked for specifics, he suggested pooling resources. “If $1,000 per capita is not enough [for people to survive], there’s a lot you can do if you pool your monies–franchising, manufacturing, businesses that have the ability to supply something. Voluntarily, as members, we could do this. If the tribe presented it to us as individual shareholders it would make it easier and if we had a business committee that knew how to invest. A $50 monthly cut in per capita could be invested by the tribe. It could create more revenue and jobs.”Regarding tribal policies, Fryberg expressed concern about structure. “I think there should be more emphasis on the other coat. In dealing with society, you have to wear two coats. One with your tribe and the other with the U.S. There isn’t enough emphasis on what they wear when they’re home. The policies have to change in terms of our leadership. Who are our leaders?” To illustrate his point, Fryberg pointed to the Onadaga in New York. “They “raise” leaders rather than choose based upon popularity. We’re left with the leadership that the federal government gave us–a Board of Directors.”

To better serve the needs of its off-reservation members, Fryberg wants the tribe to support cooperatives. “If more individuals were sharing, there’s the possibility of owning businesses and housing off the reservation. We could invest in, build, or occupy, as added income and owned property.” He emphasized the importance of water conservation and noted NWIC recycles their water. “We need to look at where we go from here, look at the environment, and go back to our customs. Solar would be good. We wouldn’t be supporting Keystone or pipelines. And it could create revenue for our tribe. It speaks to sustainability and supports our sense of identity, of who we are as a people.”

Photo/Kyle Taylor Lucas

Jennifer Cordova-James

Born and raised on the Tulalip Indian Reservation, Jennifer Cordova-James, 22, is the daughter of Chris James and Abel Cordova. She is an enrolled Alaska Native of the Tlingit Indian Tribe. Her mother is Tlingit and her father is Quechua, of Peru. She has learned the traditional dishes, music, musical instruments, and regalia, but has not learned as much as she would like about her Peruvian people. Cordova-James said the same is true of her Tlingit people.

Cordova-James has resided off-reservation to attend Northwest Indian College (NWIC) the past nine months. She is pursuing a Bachelor’s Degree in Education and has moved back home to the reservation for the summer. She will graduate next winter and, afterwards, wants to return to Tulalip to work in administration or perhaps to do marketing for the casino.

Asked about paying for college, Cordova-James said, “Scholarships! My biggest funders are the American Indian College Fund, the Comcast Scholarship, and the Embry American Indian Women’s Leadership Project Scholarship.”

In terms of employment, Cordova-James spoke highly of the excellent work experience she gained in working at the tribal hotel.Her biggest challenges have been balancing her studies with extra-curricular activities. She has served on student executive board as vice-president of extended sites where she gathered concerns, suggestions, and ideas, at each of the NWIC sites to ensure that student voices were heard and resolved. She regards these as important learning experience while also being “fun years.”

Cordova-James said the greatest disadvantage of living away from the reservation has been “Trying to make a home away from home. I lived in the dorms and the biggest issue was missing home. I suppose a huge challenge for me were family issues or obligations. I would have to make hard choices about who to support. It was my second year moving out, but I come home for summer with family and community,” said Cordova-James.

She noted employment as a second disadvantage, “There were a lot of times that I filled out applications and finally decided to focus upon my studies. The work study positions filled up really fast.”

In terms of access to healthcare, Cordova-James said she had access to the Lummi clinic, but chose to visit the Tulalip health clinic on the weekends. The ACA helps in that she is on her parent’s health plan until age twenty-six.

Cordova-James enjoyed a great sense of community while attending NWIC. “Lummi welcomed me with open arms. The campuses are full of students from other Nations. Navajo, South Dakota, Lakota, Eskimo Inuit, Alaska, and from Canada.”

Enthusiastic and ambitious, Cordova-James has big ideas and plans. In March 2014, she was elected as Northwest Regional Representative to the American Indian Higher Education Consortium. They help tribal colleges and universities with foundation and grant funding, lobbying in Washington, D.C., and in Olympia.

“Also our big initiative is a culture exchange program within the tribal college. We want a program where tribal colleges and universities work together. Sometimes it feels like they’re working against each other. We want a program that includes common requirements. Right now, we’re brainstorming and tasking people to conduct research this year. It probably won’t be off the ground for a couple years, but it’s an initiative that we’re looking into–long term,” said Cordova-James.

Speaking to the crisis of drugs on the reservation, she said, “It’s heartbreaking, especially when you’re close with somebody and you went to school with that individual. It’s sad to see young tribal members dying. We need to support them, but not enable them. We need to educate the families.”

Cordova-James said it was interesting to get the question because she and her friend and classmate, Tisha Anderson-McLean, Tulalip, co-partnered on writing a grant proposal for their class final. She said, “We called it the “Quascud Traditional Housing,” which, in Lushootseed, means lightening the load or pulling forward in the canoe when someone’s having a hard time paddling. It was for traditional housing, directly for those members who are coming out of treatment to a journey of wellness.”

Quascud Traditional Housing would offer life skills classes, help with professional attire, interview and job hunting classes, and assistance applying to school and scholarships. “Sweat lodge, culture days, and bringing a traditional healing aspect to support the journey of wellness” would be emphasized, said Cordova-James. The facility is envisioned as an apartment to ensure privacy for those who want to be by themselves. Family visits are included, but it would be a closed facility with no overnight stays, and would include checkout passes in an earned program “We compared ours to Muckleshoot and one other,” said Cordova-James who acknowledged Myron James Fryberg for his support in brainstorming and advising on the proposal.

Cordova-James said, “We got a really good grade, we got an ‘A’ for that! We saw it had huge potential for carrying forward.” Although they have not yet done so, they plan to share it with the tribe. If she doesn’t have enough on her plate, Cordova-James is also a busy activist. “I like supporting the environment,” she said, adding that she worked on I-522–the Genetically Modified Organism (GMO) labeling initiative this past year. She also worked against the XL Pipeline and coal trains. “I was protesting. There’s one picture with ‘Idle No More’ on my face. Generally, I work against big corporations trying to kill small businesses and I’m interested in the international issues such as Australia versus Japan on the whaling issue.”

Anonymous Stories

In keeping with all of Indian Country, the effects of historical trauma are equally as devastating among urban Indian populations. It is reflected in the prevalence of social, mental, physical health, and substance abuse problems. Yet, the urban Indian population is treated as invisible with little funding devoted to services to improve the quality of their lives, indeed–their life chances.

Jan – Lakota Sioux

Some stories are so painful, so personal, that to protect their families the storytellers ask to remain anonymous. Using a pseudonym, Jan, 56, is Lakota Sioux from Standing Rock, South Dakota. Born and raised in Washington, she was in the first class of The Evergreen State College. An early activist, she recalled with some nostalgia the alliance of Native students who made and sold fry bread to help the American Indian Movement (AIM) at Wounded Knee. However, her activism began with the fish wars. “When I was in high school I became involved in environmental things, and then I became involved politically around AIM. It progressed from there. The way I’ve always looked at it, you don’t have to live on the reservation to know what is right or wrong. You don’t need to live there all your life,” said Jan.

At 19, Jan left college to live with her grandparents in South Dakota. “My grandma is Lakota and lived her whole life on the reservation. Though I visited them as a child, I wanted to connect with what I didn’t learn. I wanted to know my relatives and to experience first-hand what it was to live on the reservation,” said Jan. It was an exciting time during the early seventies and the beginnings of the American Indian Movement. “I went to the very first International Treaty Convention at Standing Rock,” said Jan.

She worked part-time for a cleaning business owned by tribal relatives on the reservation, then as a public school tutor’s aid, and doing odd jobs. In her free time, she went to Sundance.

Before long, she was married with a child, but her husband died in a mysterious swimming hole accident at Standing Rock. She moved back and forth between Washington and South Dakota and eventually worked on the film, “Thunderheart,” and her son was one of the village children in the film “Dances With Wolves”, playing with Dennis Banks’ children.” My son was healthy. He played soccer. He met Billy Mills. I have a picture with the two of them on the front page of a local paper. He even went on a 3-mile run with Billy Mills,” said Jan, proudly.

While living in South Dakota, she took her son to the tribal clinic. Yet, over the years, lack of access to IHS healthcare for him grew more difficult. She finally settled back in Washington and attended vocational school in 1992.

Jan’s life took a turn as her son grew into his mid-teens. He became unmanageable and she sent him to boarding school, where they determined he was an alcoholic. He went to treatment. Said Jan, “He was in jail for a whole year, and I wondered why he was acting like this. Something’s wrong here. And after he got out and had his daughter, then he got his diagnosis. Until then, I thought he didn’t have a dad, and his hormones are acting up, and he’s acting out. It started when he was around 15.”

He became violent and was eventually diagnosed with schizophrenia, in his late teens. That was complicated by his alcoholism, his involvement in gangs, and recurring arrests.

For most people, we have children, raise them, and then they go off to live their own lives. In Jan’s case, that has not, nor will it ever be the case. Since his late teens, her son has been jailed for Drunk in Public (DIP) more times than she can recall. On two occasions, he was jailed for a year at a time and other times too numerous to count–for months on end.

His dual diagnosis of alcoholism and mental illness makes treatment, which is often unsuccessful for any alcoholic, impossible for her son. Jan reports that upon his release from jail for DIP or domestic violence, he drinks within minutes. When he leaves treatment, he immediately drinks. “I tried to get my son into treatment through the Northwest Region in Portland, but they didn’t think he was a candidate. It was an alcohol and drug treatment program, but they didn’t have a mental health component. How can you have somebody in recovery that doesn’t have rational thought process?” Jan emphasized that alcohol treatment programs must have a mental health component. “They need to have a communal living situation, but they can’t come and go as they please. It almost has to be a lock down place. There has to be something there for them to do, nutrition, exercise, garden,” said Jan.

Jan said treatment and work release require getting to class and work, but her son doesn’t have the rational thought process to do that. She suspects his long-term alcohol abuse and maybe meth use as potential factors. “And it’s worse now because he now has black-outs. Dual diagnosis. Mentally Ill and Chemically Affected (MICA). They changed the name to co-occurring disorder. Then, they shut that program down due to lack of funding.”

Pointing to the ACLU, Jan said, “Oh mentally ill people do have rights. They have rights to be able to have a place to live. Yes, they have rights. How do we solve all of that if they can’t manage themselves? How is harm measured? You have to hurt somebody and kill somebody. My son has DIP charges all the time. He has a felony record, which is why he can’t get a place to live. Even when he does, all the others running around who are just like him make him lose it. He’s the Robinhood of the streets. I bought him a brand-new jacket and it’s gone.”

She can’t have him live with her. He loses, gives away to street people, or spends all his money on drinking; he often has no place to stay. Other times, he has been evicted yet again. He is on Social Security Disability. In the winter months, she gets him a hotel room. The rest of the time, “I had to take a hard breath and say “no” when he wanted to stay at my house. There were times I let him stay with me, but he goes through my stuff and has stolen from everyone in my family. He brings street people here. I just had to feel rotten and just do it. I had no other choice, “said Jan.

She found a support group that gave her hope, “Mothers of Adult Mentally Ill Sons.” Yet, as the meetings progressed, and the leader advised them “there is no hope,” and their numbers decreased with only four people in attendance at the end. “There was one lady that had two sons like my son and they were worse than him,” said Jan. “My son can go to treatment all he wants and that’s not going to help him. He can go to jail all the time, and it’s not going to help him. The only saving grace of him going to jail was his detoxing. But the day he gets out, he drinks. I’ve resigned myself that there is no hope under the current conditions, under anything they now have.”

“My hope is not of him recovering from his mental illness, but I hope for a secure place like a compound or communal place where he could be safe. There are places around the U.S., but they cost $20k to $30k a month. Basically, at the heart and core of his being is a pretty good person, but his illness gets in the way just like any alcoholic.”

Asked how she coped and took care of herself, Jan said at first it was by attending National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI) and co-occuring disorders meetings. “I started educating myself. That helps to a point, but like the other day when I took him to the dentist, when he got into the car, he had a psychotic episode. It just kills me inside and it hurts and I just want to die. Just get this pain away. Take this pain away. Because he’s in pain. I feel sad for my son because of the way he has to live. Any mother who has a son or daughter who has to live that way–it’s just painful and hurtful. I cope with it by talking to my friends, and talking to my brother, and talking to my partner who now understands. Boundaries is a big word. I’m tougher on my son than some mothers are. And I cry. You know it’s part of coping–if you can call it that. Crying is relief. Sometimes, you just cry. Also, just being involved in other things. I’ve been involved with my granddaughter, helping her as much as I can. Just being there for her. I’ve screamed and I’ve hollered when I’m driving down the road. I go to the YMCA,” said Jan.

Anonymous

Among other anonymous stories, there are the Indian women in their late fifties and early sixties living urban and alone, struggling month to month with few resources.

There is also the thirty-year-old Puyallup woman who spends her days at the Tahoma Indian Center and looks for a safe place to sleep at night. She has been unable to find work. Sometimes, she stays at the mission, but she worries about the bugs, so she often sleeps on the streets. She seems detached as she speaks about drinking. She “grew up with it.” It is surprising to learn that her mother who is only 53 is in a nursing home. Asked if illness caused her young mother’s placement in the home, the flat reply was, “No, she has wet-brain.” An inquiry about it was met with an incredulous reply, “You’ve never heard of wet-brain! My mother drank so much for her whole life, so it pickled her brain and she cannot take care of herself.”

Wet-brain is a real condition known as Wernicke-Korsakoff syndrome caused by long-term alcoholism. Its symptoms include mental disturbance; confusion; drowsiness; paralysis of eye movements; and staggering gait. It is primarily caused by a lack of thiamine (Vitamin B1) due to severe malnutrition and poor intestinal absorption of food and vitamins caused by alcohol. The wet-brain person acts much like the Alzheimer’s victim with loss of recent memory, disorientation to time and place, confusion, and confabulation (telling imagined and untrue experiences as truth). In its early stages, it can be prevented, but it cannot be undone.

Fifty-two year-old Jack is bright and well spoken. He is Canadian First Nation, but was born in Seattle in 1960. He hasn’t visited his home reserve in more than 30 years. Jack served four years in the Army, stateside. “I really enjoyed my military service. I learned a lot and regret not staying in. It had a lot of security,” said Jack.

Jack started visiting and found a home in the Tahoma Indian Center in the early 90s. As for now, he said, “I’m doing alright, staying alive.” After the service, he got labor work, mostly moving. Today, he does recycling.

Due to his parents’ drinking, he and his siblings were put into foster care early, two or three homes while he was very young. He was five when he was permanently placed into the system, “but I have blocked a lot of it out,” said Jack.

He admits to being an alcoholic, which sometimes prevents his access to the mission. Asked when he began drinking, Jack replied matter-of-factly, “Probably in the womb.” He said he never knew his mother not drunk.

In the next moment, Jack offered, “I learned a lot about natural foods and nutrition and quit drinking in the mid-80s to early 90s. I took up running and ran 26.2 miles in the Goodwill Games. We started at Gasworks Park. My time was 4 hours and 3 minutes. If I could come up with the equipment, I would probably resume running.” He confessed that he is “always dreaming. One of my goals, too, is to climb Mount Rainier.”

“For fun, I like to read–Dean Koontz, Stephen King, history, philosophy, political science, Indian–contemporary and history,” said Jack. He brightens even more in recalling a local doctor who for about seven years took the center rafting on the Deschutes in Oregon. He misses that.

Another Jack, Lakota, Sioux, spoke of how difficult it was to secure health care in Washington State. One local tribe turned him down, so he had to travel long distance to the Seattle Indian Health Center. He is now happily enrolled in an ACA plan.

Summary

Despite a sense of exclusion for some and of being “less than” experienced by others, most urban Indians continue to identify with their people, reservation communities, villages, and land. They share a common history and memories. Displaced from their reservations they seek community ties with other urban Indians. Yet they yearn for connection to their land, people, culture, and traditions. They seek common ground and to ensure they are not forgotten.

As noted by the Urban Indian Health Commission, “Today’s urban Indians are mostly the products of failed federal government policies that facilitated the urbanization of Indians, and the lack of sufficient aid to assure success with this transition has placed them at greater health risk. Competition for scarce resources further limits financial help to address the health problems faced by urban Indians.”

The mass migration of Indians from their reservations to urban centers has been devastating in myriad ways, but most glaring are the economic, social, and health struggles endured by newly urbanized Indians and their families.

Then, beginning in the nineties, federal devolution to the states and local government in the form of block grants accompanied by more severe state restrictions to services has resulted in even more devastating service cuts to already impoverished urban Indians. They’ve experienced adverse impacts from entitlement reform and cuts to funding levels, major cuts to social service safety net programs, public housing, and jobs.

The stories of untreated illness and dental emergencies, racial police profiling and an unjust criminal justice system, discrimination in access to services, disproportionality in Indian Child Welfare, and preventable death, homicide, and suicide are legion among urban Indian communities.

Yet, the hard data is still missing; legends don’t qualify on grant applications for increased federal funding. Though they do not wish to be named, urban Indian organizations speak to horrific funding challenges often due to tribal government opposition to their federal funding requests. Tragically, as across Indian Country, the effects of historical trauma are prevalent in social and substance abuse among the urban Indian population. Yet, they are treated as invisible.

There is urgent need to address prevention and intervention, especially for urban youth. Some positive trends include the Washington State Legislature’s convening of a taskforce to address racial disproportionality in the child welfare system. While this year’s report to the legislature showed improvements overall, in its “Detailed Findings,” the report indicates, “Racial disproportionality in all intakes has decreased slightly in 2012 for all groups except Native American children, and disproportionality in screened in intakes has decreased slightly for all groups except Native American and multiracial children which had a slight increase.”

Yet, despite all the strife, there is incredible resilience among urban Indians, many of them generational, and those who have recently migrated away from their reservation communities. Many Indians residing in metropolitan areas are attending college or university, are pursuing career paths, serving in local government, and are active in their communities. They’re active in social and environmental justice efforts.

It is evident that urban Indians, most often invisible to policy makers, must become their own best advocates with their on-reservation relations, with tribal leadership, and with allies and policymakers in their urban centers.

Kyle Taylor Lucas is a freelance journalist and speaker. She is a member of The Tulalip Tribes and can be reached at KyleTaylorLucas@msn.com / Linkedin: http://www.linkedin.com/in/kyletaylorlucas / 360.259.0535 cell

Being Frank: Listen to the Planet

Note: Being Frank is the monthly opinion column that was written for many years by the late Billy Frank Jr., NWIFC Chairman. To honor him, the treaty Indian tribes in western Washington will continue to share their perspectives on natural resources management through this column. This month’s writer is Ed Johnstone, treasurer of the NWIFC and Natural Resources Policy Spokesperson for the Quinault Indian Nation.

By Ed Johnstone, Quinault Indian Nation, NWIFC Treasurer

OLYMPIA – Our planet is talking to us, and we better pay attention. It’s telling us that our climate and oceans are changing for the worse and that every living thing will be affected. The signs are everywhere. The only solution is for all of us to work together harder to meet these challenges.

We are seeing many signs of climate change. Our polar ice caps and glaciers are melting and sea levels are rising. Winter storms are becoming more frequent and fierce, threatening our homes and lives.

It is believed that we are witnessing a fundamental change in ocean and wind circulation patterns. In the past, cold water full of nutrients would upwell from deep in the ocean, mix with oxygen-rich water near the surface, and aid the growth of phytoplankton that provides the foundation for a for a strong marine food chain that includes all of us.

The change in wind and ocean patterns is causing huge amounts of marine plants to die and decompose, rapidly using up available oxygen in the water. The result is a massive low oxygen dead zone of warmer waters off the coasts of Washington and Oregon that is steadily growing bigger, researchers say. Large fish kills caused by low oxygen levels are becoming common, at times leaving thousands of dead fish, crab and other forms of sea life lining our beaches.

Low oxygen levels and higher water temperatures are also contributing to a massive outbreak of sea star wasting syndrome all along the West Coast. It starts with white sores and ultimately causes the star fish to disintegrate. While outbreaks have been documented in the past, nothing on the scale we are seeing now has ever been recorded.

We are also seeing basic changes in the chemistry of our oceans. Our atmosphere has been steadily polluted with carbon dioxide for hundreds of years. When that carbon dioxide is absorbed by the ocean, those waters become more acidic and inhospitable to marine life. Young oysters, for example, are dying because the increasingly acidic water prevents them from growing shells. Researchers say that ocean acidification could also amplify the effects of climate change.

Because we live so closely with our natural world, indigenous people are on the front line of climate change and ocean acidification. That is part of the reason that native people from throughout the Pacific region will gather in Washington, D.C. in July for our second First Stewards Symposium. Tribal leaders, scientists and others will examine how native people and their cultures have adapted to climate change for thousands of years, and what our future—and that of America—may hold as the impacts of climate change continue.

President Obama’s commitment to addressing adaptation to climate change in a real and substantive way is encouraging. Tribes stand ready to partner with the Administration and others any way we can to protect our homelands and the natural resources on which our cultures and economies depend. Only by all of us working together – supporting one another – will we be able to successfully face the challenges of ocean acidification and climate change.