Brenda Austin, ICTMN

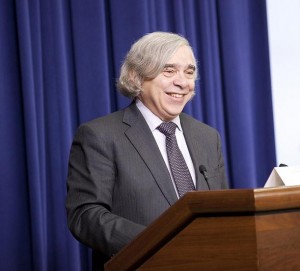

Patrice Kunesh is the Deputy Under Secretary for the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Rural Development (USDA-RD). She began her tenure at the USDA on May 22, 2013, and among her many responsibilities are the oversight of Operations and Management, the Office of Civil Rights and she also works with the state directors.

According to a USDA press release, during fiscal year 2013, Rural Development’s electric programs invested a historic high of $275 million for new and improved electric infrastructure to more than 80,000 American Indians and Alaska Natives. That total includes a loan for copy67 million to the Navajo Tribal Utility Authority in Arizona. Through their Community Facilities program, Rural Development invested copy14 million this year in 73 loans and grants, representing a 600 percent increase over FY 2012. Of that funding, $3 million (24 grants) was provided to tribal colleges and universities. Rural Development also made their largest single investment to a tribe this year to help the Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians finance a new healthcare facility in the form of a $40 million direct loan and a copy0 million loan guarantee.

Deputy Under Secretary Kunesh recently spoke with Indian Country Today Media Network about Rural Development’s program assistance to American Indian tribes, goals for 2014 and her own interest in Indian country.

With your background in tribal law, governance and economic development, what made you want to make the leap to USDA Rural Development?

It was an opportunity I couldn’t refuse. I was teaching at the University of South Dakota School of Law and received a call from the White House asking if I would consider coming to Washington D.C. and working on behalf of Indian Affairs in the Solicitors Office at the Department of the Interior (DOI).

Then around the election I received another call from the White House saying that I have done good work for the Administration and would I consider branching out. They asked me where might I go and the USDA was at the top of my list.

In the back of my mind I have always had great admiration and appreciation for USDA. As a young mother of two little ones I had received food stamps for a number of years. I also was a recipient of WIC (Women, Infants, and Children) vouchers. I lived in public housing and went to public health clinics. It was a precarious time for me. I was able to continue my education and earn a college degree because I had food stamps.

Rural Development is about serving rural America, and Indian country is synonymous with rural America. And the needs of rural America are synonymous with the needs of Indian country.

USDA Rural Development has invested in tribal infrastructure, housing, education and health, both in grant funding and loans. Is there anything that tribe’s can or should be doing to take advantage of what Rural Development has to offer?

I don’t think tribes are doing enough. Tribes don’t know generally what we can do in terms of our programs and in terms of housing, business and utility infrastructure.

One of the things I am doing with my colleagues in Natural Resource Conservation Services, the Farm Service, the Office of Tribal Relations and our Food and Nutrition Services is to spread the word wherever we possibly can. So as busy as this week was with our observances of Native American Heritage Month and the White House Tribal Leader Summit we are working with other federal agencies such as the Departments of Energy, Commerce and the U.S. Treasury, as well as the Department of the Interior, to let tribes know there is a whole host of support that we can provide to them that they may not realize is available to them.

To my great surprise and tremendous appreciation I find that Rural Development alone last year invested $660 million in Indian country. That is tribal colleges and tribal schools, health clinics and an abundance of housing that we have built on Indian reservations.

But more than the investments that Rural Development has made in terms of funding, we have really forged wonderful relationships with Indian tribes. And much of this work in the field has taken many years of developing the trust, rapport and respect of tribal leaders, and to help provide the technical assistance tribes may need to get the grant or loan application in to be awarded these funds.

What are your goals for working with tribes in 2014?

In 2014 we are going to be trying to establish significantly more partnerships across the federal government and with tribes. Our top priority right now is that we need Congress to provide a comprehensive multi-year Food, Farm and Jobs Bill as soon as possible so we can ensure for all Americans, as well as tribal governments, that Congress is committed to supporting rural America and Indian country.

We need to put nutritious food on the table in Indian country and we need to invest in good food for tribal youth in schools. We need to continue improving infrastructure in tribal communities and that goes well beyond community centers and clinics – it’s about growing local and regional food systems to feed Indian people. It’s about reviving traditional foods that tribes have historically cultivated. It’s educating Native students at every level. So we have tremendous goals both in Rural Development and throughout the USDA.

With the current state of our economy, under funded health care and the effects of sequestration on tribal governments and employees, what relationship would you like to see this year between Rural Development and tribal nations?

We can only do this work in partnership – and the partnership between the federal government and Indian tribes is really based on a legal obligation, and I would say a moral obligation. This partnership has been our purpose since we participated in the first White House Tribal Nations Conference in 2009, but it goes beyond that in terms of trust responsibility and a trust relationship that drives us to work with tribes across the nation.

This year president Obama established the White House Council on Native American Affairs and that is to further expand the federal tribal collaboration and understanding. We are proud of our results thus far. I think we have stepped up to provide a coordinated response to many of the needs in Indian country.

We also have to recognize that our veterans have served our nation with great pride and are part of the picture here too. Native American veterans have served in greater percentage per population than any other segment of the population. We truly see that as remarkable, but also an opportunity for us to give back to them to support them and to include them in our work in very meaningful ways.

Do you believe current funding for Rural Development is at a level that can meet the needs of American Indian and Alaskan Native programs?

Definitely no. The budget is not sufficient to meet the needs in Indian country, but it’s not sufficient to meet the needs in rural America either. Rural America is the heart of the United States and the work that rural America does drives the U.S. economy in terms of feeding us and supporting all the things that we need in the U.S. and is so incredibly important. The budget is not sufficient and we really do need to look at funding levels that truly are reflective of the contributions that rural America makes and what we can provide to enhance that as well.

You are invested in Native communities and are personally of American Indian descent, did you grow up in a rural environment knowing your tribal culture and traditions?

My mother was a member of the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe and her father was born on the Fort Berthold Reservation in North Dakota and grew up on the Standing Rock Reservation. My grandfather left the reservation due to the harsh conditions at the time in the early 1900s.

I grew up in Minnesota knowing and feeling very grateful for our Indian family on the reservation. My father worked for Indian tribes through the Youth Conservation Corp and we participated in more of the Ojibwe culture at the time then the Lakota or Sioux communities. At that time it was the American Indian movement and a lot of Indian people were very concerned about how we were going to maintain cohesive coherent cultural ways and build strong tribal governments. And I think it was from that work and from hearing my mother talk about growing up on the reservation that I decided this is what I want to do with my life. I decided I wanted to do what I can to improve and secure the wellbeing of Indian children. That is how I started my work and that’s how I think of my work right now – through the lens of child wellbeing.

Read more at http://indiancountrytodaymedianetwork.com/2013/12/09/6-questions-usdas-kunesh-need-tribes-use-programs-152578