The iconic Chinook salmon, for millennia a cornerstone of Pacific Northwest diet, spirituality, ceremony and even the tribes’ economy, is fast becoming toxic in Washington State.

And rather than focus on cleaning up the waterways that year-round salmon reside in, Washington state agencies have issued fish-consumption advisories. The less fish consumed, at the lower limits, the higher concentration of contaminants is deemed acceptable.

But salmon are not just a way of life. They are life. And, Northwest tribes say, the cavalier attitude toward their contamination not only risks health but also guts treaty rights and the very way of life of the land’s original peoples.

Studies of adult salmon indicate that Puget Sound Chinook salmon have higher concentrations of legacy contaminants, such as polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), than salmon from other parts of the Northwest. The state’s solution? Limit consumption to one Puget Sound Chinook fillet a week, and two Puget Sound resident Chinook (blackmouth) fillets a month.

Tribal peoples in Western Washington who eat their usual intake of fish and seafood–indeed, the traditional foods they have eaten for millennia–must do so now at risk of disease due to the toxins that lurk in their waters, not to mention in their state politics. People who eat fish more than once a month are not protected by Washington State water quality standards.

Fish, with their high levels of precious proteins and rich omega-3 fatty acids, are touted as improving health and extending life. But fish from polluted waters can expose unborn babies, infants, children and adults to mercury, lead, arsenic, PCBs and other toxins that can compromise immune function, cause cancer and adversely affect reproduction, development and endocrine functions.

Washington State’s Department of Health recommends that residents eat no more than two fish fillets a week, in concert with very strict selection, preparation and cooking criteria, to avoid toxicity. Compare that with Washington State’s Department of Ecology’s fish consumption rate (FCR) determination of an eight-ounce fish fillet a month, or 6.5 grams a day.

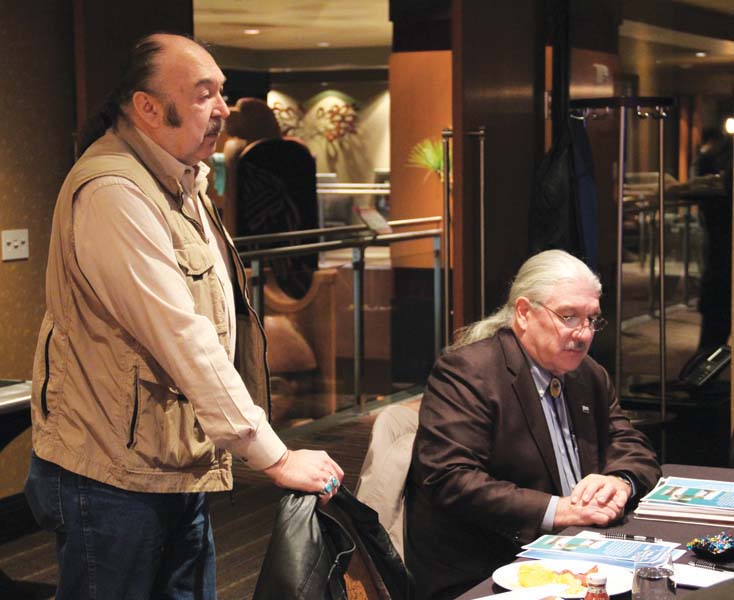

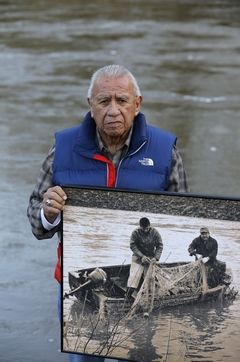

“Washington uses one of the lowest FCRs in the nation to regulate pollution in our waters,” said Billy Frank Jr., (Nisqually), chairman of the Northwest Indian Fisheries Commission.

RELATED: Salmon Restoration, Part 4: As the Salmon Goes, So Goes the Northwest

The less fish consumed by residents, said Frank, the more pollutants that can be dumped into waterways. The higher the fish consumption rate, the cleaner that Washington waterways will need to be. Establishing a higher consumption rate will force polluters to reduce the amount of new contaminants they dump into the water, keeping salmon and other seafood clean.

Studies reveal that Washingtonians are among the highest fish-consuming populations in the nation. That’s not surprising given that 29 federally recognized tribal nations exist within a state bound by the Pacific Ocean, the Columbia River and the Salish Sea, with the state itself wrapped around Puget Sound and interlaced with numerous rivers.

“State government admits that the current rate does not protect most Washington citizens from toxics in our waters that can cause illness or death,” said Frank. Washington’s rate should be at least as protective as Oregon’s rate of 175 grams per day, equivalent to about 24 eight-ounce fillets per month, Frank said.

The Columbia River Inter-Tribal Fish Commission’s (CRITFC) 1994 fish consumption survey revealed that the average Columbia River tribal member consumed 58.7 grams of fish per day, and also found that they typically ate the whole fish. The survey prompted Oregon to revise its FCR in 1994, which Oregon updated in 2011 in line with U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) recommendations. But industry in Washington, led by Boeing, say that Oregon’s standard is impossible.

Frank said the effort to adopt a more accurate FCR is one of the biggest public policy battles in the country, pitting human health against the economy.

“Industry leaders such as Boeing are digging in their heels to delay or kill rule-making on a more accurate rate because they say it will increase their cost of doing business,” he said.

“Tribal leaders were very disappointed when [Washington] failed to adopt fish consumption standards in 2012,” Ann Seiter, the FCR coordinator for the NWIFC, told ICTMN in reference to InvestigateWest’s five-part series on the issue in 2012.

InvestigateWest’s insightful five-part-plus series describes how former Governor Christine Gregoire was divided between acting for the tribes, powerful supporters who wanted stricter water pollution rules, and her supporters in the aerospace industry, like Boeing, which were against tightening FCR rules, in 2011–2012. Ecology stopped work on changes to water pollution rules in June 2012 with a delay to at least 2014, after which Gregoire would no longer be governor, the team reported.

“The tale of how Boeing and its allies beat back … Ecology’s attempt to change a fish consumption rate that pretty much everyone involved acknowledges is too low provides a fascinating look at how the levers of power are pulled in Olympia,” InvestigateWest said.

The tribes are upset with the continuing delays.

“They’ve taken their concerns to the EPA regarding their Trust responsibilities, as well as their obligations under the Clean Water Act,” Seiter said.

Under the federal Clean Water Act, river water should be clean enough so that people can eat the fish. Environment and fisheries organizations sued the EPA in October 2013 for non-compliance under the Clean Water Act for allegedly failing to protect Washingtonians from toxic pollution entering Puget Sound, the Columbia River, the Spokane River and other waterways.

In a letter to Ecology last June, the new Governor Inslee announced that he would organize an informal group of advisers from local governments, Indian tribes and businesses, according to InvestigateWest. Inslee’s letter to Ecology Director Maia Bellon, released last June 7, called for the agency to help educate Inslee’s advisory group, “including real-world scenarios illustrating how new criteria would be applied and how new implementation and compliance tools would work in the permitting context,” they reported. Ecology officials had already said the “implementation and compliance tools” could include giving businesses up to 40 years to cut pollution levels to the amount that presumably would be required once accurate fish-consumption rates are in place.

Tribal leaders responded by taking their concerns directly to Inslee, Seiter said.

In December China banned shellfish from the West Coast, citing, among other factors, high levels of inorganic arsenic in geoduck clams harvested by the Puyallup Tribe in the Redondo area of Puget Sound, according to Earthfix.opb.org. The ban underscored the direct negative economic impact of pollution on tribes.

“The tribes are not only interested in protecting all the species of fish they eat, but they’re also concerned about protecting their economic interests,” said Seiter.

Washington business associations, cities and counties together hired an engineering firm to prepare a report, released on December 4, 2013, that evaluated technologies potentially capable of meeting Ecology’s effluent discharge limits for revised human health water quality criteria for arsenic, benzo(a)pyrene (BAP), mercury, and PCBs. The report coincided with the public rollout and comment period for Ecology’s proposed rule changes to the state’s water quality standards in early 2014, including human health criteria involving the FCR.

“Currently there are no known facilities that treat to the [health water quality criteria] and anticipated effluent limits that are under consideration,” the report stated. It also reported limitations in proven technologies capable of compliance with the revised health water quality criteria.

One tribal official who spoke on condition of anonymity said tribal leaders are sticking close to these issues.

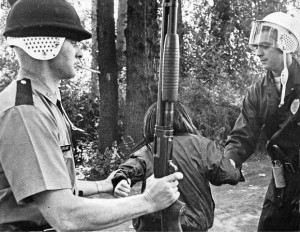

“As we discussed this ongoing environmental catastrophe, we decided we wouldn’t go to jail anymore like we did in the fish wars,” the leader told ICTMN. “But we are ready to go to war [to] protect the water.”

Related: Fish Consumption Rate Needs Updating