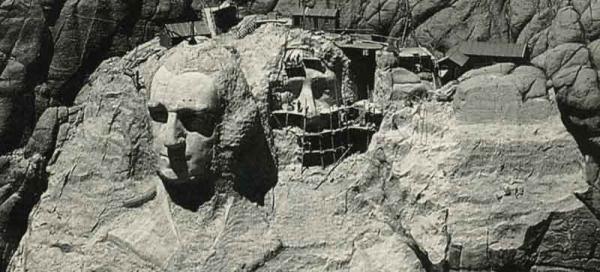

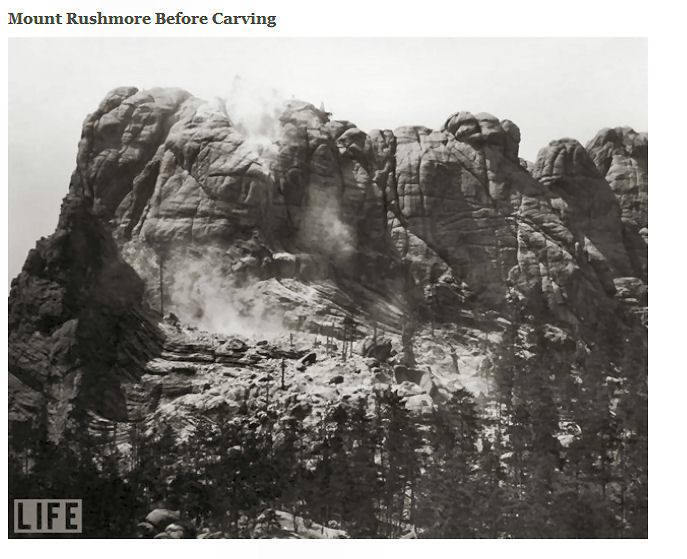

The carving into the mountain the Sioux call Six Grandfathers began October 4, 1927.

This Date in Native History: On October 4, 1927, sculptor Gutzon Borglum began carving the faces of four presidents into the granite of the sacred Black Hills.

Christina Rose Oct. 4, 2013 Indian Country Today Media NetworkFor the Lakota, the slashing of the stone exemplified disrespect in itself, but beyond that, there was something almost mocking about having four American presidents, all of whom had supported genocidal Indian policies, looking down at the Lakota people.

The heads of each of the four presidents measure 60 feet high and the monument took six and a half years to complete.

The presidents represented on the face of the mountain the Sioux called Six Grandfathers had some terrible Indian policies, here are some highlights:

Lincoln was responsible for hanging the Dakota 38, the largest mass hanging in U.S. history.

RELATED: Debunking Lincoln, the ‘Great Emancipator’

George Washington declared an all-out extermination against the Iroquois people in 1779.

RELATED: George Washington Letter Describes Killing of Natives as ‘Villainy’

Thomas Jefferson supported a policy of assimilation, and failing that, extermination of the Cherokee and the Creek. He said all Natives should be driven beyond the Mississippi or, “take up the hatchet” and “never lay it down until they are all exterminated.”

Theodore Roosevelt, who, shortly after being elected governor of New York, announced, “This continent had to be won. We need not waste our time in dealing with any sentimentalist who believes that, on account of any abstract principle, it would have been right to leave this continent to the domain, the hunting ground of squalid savages. It had to be taken by the white race.”

Mount Rushmore was carved into the land that was promised in perpetuity through the Treaty of 1868. The Black Hills are central to the creation stories of the Lakota, where they have always lived and prayed. However, the 1860s were a time when promises were made, but soon broken. In 1877, gold was found in the Black Hills and the land was confiscated by the U.S. government. To this day, the Lakota have refused payment for the land of their origins.

One well-intentioned, if unpopular, result was that in 1939, Henry Standing Bear, Lakota graduate of Carlisle Indian School, wrote a letter requesting Connecticut sculptor Korczak Ziolowski come to South Dakota and carve the likeness of Standing Bear’s ancestor, Crazy Horse, into another mountain. Standing Bear wrote, “My fellow chiefs and I would like the white man to know the red man has great heroes, too.” The Crazy Horse Memorial, which is substantially bigger than Mount Rushmore, is a result of their relationship.

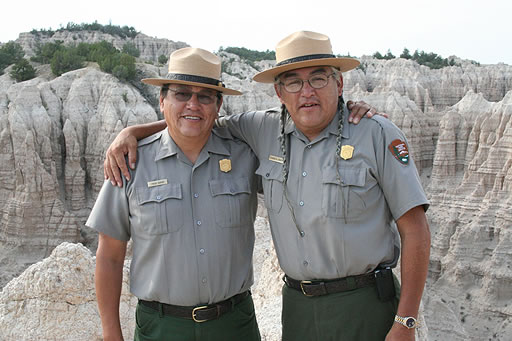

While the majority of local Native Americans agree that Mount Rushmore could not have been a more offensive undertaking, in 2003, things began to change with the arrival of the monument’s new superintendent, Gerard Baker, Mandan-Hidatsa. From the beginning, Baker set about turning over what the Rapid City Journal called “misconceptions about travel and tourism on the reservations,” addressing the questions of tourists, such as, “Do Indians still live in tipis?”

Baker, described as having long braids and standing close to 6’6”, hired two members of Pine Ridge’s Akicita (Warrior) Society and set up a Native American village. He recommended that his employees read Black Elk Speaks, and that they bone up on the Ft. Laramie Treaty of 1868. Baker took visitors to Pine Ridge’s Red Shirt Table and Wounded Knee. According to historian Donovin Sprague, Lakota, Baker truly rang in a new era.

“I think Gerard Baker did wonders up there, he got a little village going, and he faced some heat on that. I knew him from the Battle of the Little Big Horn site, and he was part of the big change up there. It had been Custer’s battlefield, and he had it renamed to reflect both cultures,” Sprague said. “Then there was, of course, the Two Cents Column of racist comments in the newspaper. He’s an outstanding person who worked for the National Parks Service since he was a young man.”

When Sprague was asked his opinion of Mount Rushmore, he sighed. “Putting the presidents faces on treaty land, I have always known all my life these things are here and not going away, so I was raised to think about it educationally. What can we do to use it to bring people together?”

Having worked with the former education director at Rushmore, Sprague said, “They [the staff at Rushmore under Baker] were very into integrated culture. We had a graduate studies credit program through Black Hills State University, where I was an instructor. They had staff for the Lakota side of history and culture, and Gerard was there to speak. There was a balancing. We had a really good working relationship during Gerard’s era.”

Baker is reportedly now working in Pine Ridge to establish a new park in the Badlands. Quoted in Esquire Magazine, Baker said, “When I got offered the job [at Rushmore], I called the elders up and asked their advice. I was expecting to hear, ‘Don’t work there. You’ll be a turncoat!’ But instead what I heard was just the opposite, ‘What a place to begin the healing process!’”

Since the monument has been closed due to the government shutdown, there is no information about whether or not the programs instituted under Baker have continued.