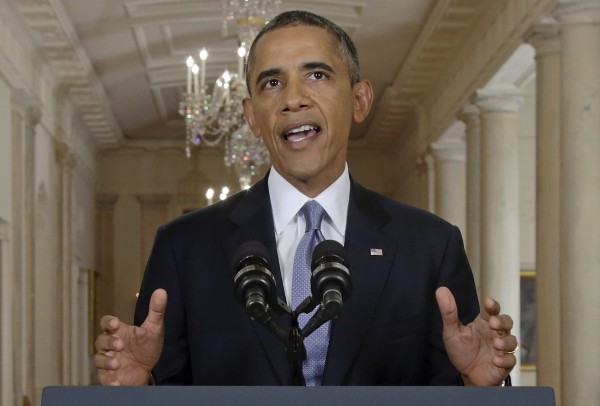

President Barack Obama addresses the nation about the situation in Syria from the East Room at the White House in Washington on Tuesday night.

By David Nakamura and Zachary A. Goldfarb, The Washington Post

WASHINGTON — President Barack Obama said Tuesday that he will seize one last diplomatic opening to avoid military strikes on Syria but made a forceful case for why the United States must retaliate for that nation’s alleged use of chemical weapons if the effort fails.

In a nationally televised address, Obama cautiously welcomed a Russian proposal that the government of Syrian President Bashar Assad give up its stockpile of chemical weapons, signaling that he would drop his call for a military assault on the regime if Assad complies.

But with little guarantee that diplomacy would prevail, Obama argued that the nation must be prepared to strike Syria. Facing a skeptical public and Congress, the war-weary president said the United States carries the burden of using its military power to punish regimes that would flout long-held conventions banning the use of biological, chemical and nuclear weapons.

“If we fail to act, the Assad regime will see no reason to stop using chemical weapons,” Obama said. “The purpose of a strike would be to deter Assad from using chemical weapons and make clear to the world we will not tolerate their use.” But he added that he has “a deeply held preference for peaceful solutions” as he pledged to work with international partners to negotiate with Russia over a United Nations resolution on a Syria solution.

The speech was a plea from a president who, defying public opinion, has pushed the United States toward using force in Syria — and staked his and the nation’s credibility on whether he can get Congress to support him. But it also followed two days of intense political and diplomatic negotiations on Capitol Hill and abroad that appear to have shifted his calculus for how quickly to move forward with direct intervention.

Obama pledged that before pursuing military options, his administration would explore a surprise offer from Russia on Monday to persuade Assad to surrender his chemical weapons to United Nations inspectors.

The president had visited Congress in the afternoon, asking senators in both parties to delay a vote on a resolution that would authorize him to order strikes on Syrian government targets in retaliation for the alleged chemical attack on Aug. 21 that reportedly killed more than 1,400 Syrians near Damascus.

A White House official said Obama spent an hour apiece with the Democratic and Republican caucuses, reviewing evidence of the attack and reiterating his decision to pursue a “limited, targeted” military strike that would not involve U.S. troops on the ground in Syria.

But the president also told lawmakers that he would “spend the days ahead pursuing this diplomatic option with the Russians and our allies at the United Nations,” said the official, who spoke on the condition of anonymity to discuss private deliberations.

The proposal appeared to be gaining traction Tuesday, as Syria embraced it and China and Iran voiced support. But a telephone conversation between French Foreign Minister Laurent Fabius and his Russian counterpart, Sergei Lavrov, revealed a deep divide over their visions of the U.N. Security Council’s role and particularly over the prospect of military action to ensure that an agreement would be honored.

There also were doubts about how Syria’s stockpiles could be transferred to international monitors amid a protracted civil war that has killed more than 100,000 people.

The call took place after France said it would draft a Security Council resolution to put the Russian proposal into effect.

The Russian offer could serve as a potential escape hatch for a president who has at times appeared reluctant to pursue military force, even after saying he believed it was the right course to reinforce a “red line” against chemical weapons. Obama has struggled to build an international coalition for such action.

And with congressional and public support for a U.S. strike dwindling rapidly over the past week, Obama’s request to delay the Senate vote bought him time to try to convince the public that the White House is pursuing a viable and coherent strategy despite a muddled message since the alleged chemical attack.

“Bottom line is we’re all going to try to work together,” said Sen. Charles Schumer, D-N.Y., after the lunch with Obama. “There is hope, but not yet trust in what the Russians are doing. But I think there’s a general view, whether people are for it or against it, there’s an overwhelming view that it would be preferable if international law and the family of nations could strip Syria of the chemical weapons. And there’s a large view we should let that process play out for a little while.”

Sen. Bob Corker of Tennessee, a key GOP proponent of a military strike in Syria, emphasized that the option of U.S. force remained viable, but he added that “it’s probably good for us just to take a pause.”

At the same time, administration officials made clear that they will not accept the Russian offer at face value or engage in protracted negotiations that indefinitely delay its response to Assad. Russia has consistently blocked U.N. action against Syria, its geopolitical ally, frustrating the Obama administration and leading the president to announce that he would pursue military strikes independent of that international body.

Secretary of State John Kerry said Tuesday that the United States would demand a Security Council resolution authorizing a strike if Syria refused to turn over its chemical stockpile, a provision the Russians promptly rejected.

Kerry told a House committee that the proposal “is the ideal way” to take chemical weapons away from Assad’s forces.

Russian President Vladimir Putin countered that the disarmament plan could succeed only if the United States and its allies renounced the use of force against Syria.

Kerry will travel to Europe this week to discuss the proposal with Lavrov, a senior administration official said later Tuesday. The meeting will be held Thursday in Geneva, where the United States and Russia hope to convene a separate peace conference on Syria, the official said.

“We need a full resolution from the Security Council,” Kerry said Tuesday during an online forum held by Google. “There have to be consequences if games are played.”

The stakes were high for Obama’s address to the nation. He has delivered just nine White House speeches in prime time, according to CBS Radio correspondent Mark Knoller, who keeps tallies on presidential appearances. Obama chose the grand East Room over the more intimate Oval Office, which is the traditional location for commanders in chief to talk to the country about war.

Experts said it made sense for Obama to delay the congressional vote because his hand would be strengthened even if the Russia proposal fails.

“It gets him out of his disastrous political mess,” said Rosa Brooks, a former Pentagon official. Obama will be able to say he made every effort to avoid a military conflict, making it “a lot easier for him to make the case for force.”

But other analysts were more circumspect, fearing that stalling on the part of Russia and Syria could give Assad time to hide his stockpile.

“The most dangerous downside,” said Jon Alterman, a former State Department official now at the Center for Strategic & International Studies, “is you get absorbed in endless processes which take you back to the status quo ante and you neither removed the weapons and you lost the momentum when there was support for action.”

– – –

Washington Post staff writers Paul Kane and Ed O’Keefe contributed to this report.