By Kalvin Valdillez, Tulalip News

At the intersection of 1st Avenue and University Street in downtown Seattle is a large sculpture of a craftsman utilizing a hammer outside of the Seattle Art Museum (SAM). For decades, the museum has been the home to a collection of diverse artwork celebrating the many cultures from around the world, including several installations and exhibits that highlight traditional Indigenous artwork such as carvings and paintings. This spring, the SAM decided to host a major exhibit that was first curated and featured at the Denver Art Museum and showcases the works of Choctaw and Cherokee Artist Jeffrey Gibson who, much like the craftsman sculpture, used a hammer to attract the masses and break into the art world, albeit metaphorically.

“Like A Hammer as a title has always been conceptually and philosophically the idea of a hammer being used as a tool of deconstruction and reconstruction,” Jeffrey stated in a video displayed within the exhibit. “In particular, like a DIY ethic. It’s this simple tool that a single person can alter something with.”

Located on the top floor showroom of SAM, the Like A Hammer exhibit invites visitors to explore Jeffery’s mind and vivid imagination as his creations serve as a reflection of who he is, all while paying tribute to the history of the art, material and words that inspire his artwork, drawing ideas from his culture, modern music and personal life.

The exhibit features over sixty-five unique pieces from Jeffery’s collection, all of which were created after 2011 following a huge revelation that found him deconstructing and reconstructing many areas of his life. In a lecture at the New York Studio School, Jeffery explained that he nearly gave up his passion after his material was rejected by several art museums and studios. He was so upset that one day he took all of his paintings to his local laundromat and put them through three back-to-back wash cycles.

After hearing this news, Jeffery’s friend recommended him to a counselor for anger management. The counselor in turn suggested physical activity as a way to take out his aggression, so he joined a nearby gym and it was here where he had his first breakthrough.

“I sat down [with my counselor] for my first session and all these issues around race, class, gender and homophobia came out very easily,” he said. “What we began talking about was this disjoint between the mind and the body. Ultimately, he recommended that I worked with a physical trainer and the physical trainer is the first one who introduced me to the bag. When working out aggression on the punching bag, my trainer would ask me to name what I was punching – to name who I was angry at, what were my obstacles. And somehow this naming and projecting, and then literal hitting, was meant to unify what was happening up here [in my head] with what was happening in the body.”

“I sat down [with my counselor] for my first session and all these issues around race, class, gender and homophobia came out very easily,” he said. “What we began talking about was this disjoint between the mind and the body. Ultimately, he recommended that I worked with a physical trainer and the physical trainer is the first one who introduced me to the bag. When working out aggression on the punching bag, my trainer would ask me to name what I was punching – to name who I was angry at, what were my obstacles. And somehow this naming and projecting, and then literal hitting, was meant to unify what was happening up here [in my head] with what was happening in the body.”

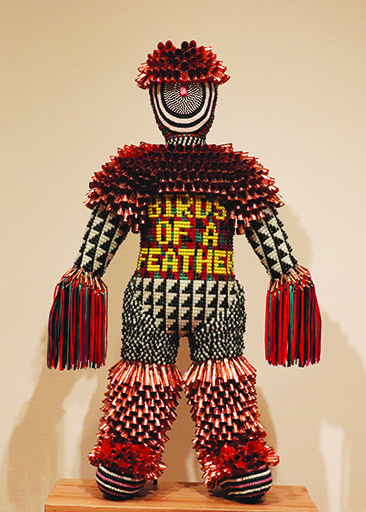

The beaded Everlast punching bag is perhaps Jeffery’s most notable work to date. Approximately fifteen colorful bags are displayed throughout the exhibit, all featuring traditional beadwork with contemporary designs. On several punching bags, Jeffery incorporates the lyrics of his favorite songs into his beadwork such as ‘If I Ruled the World’ by Nas and Lauryn Hill as well as ‘I Put a Spell On You’ by Nina Simone. In addition to lyrics and beadwork, Jeffrey also included various elements of ceremonial regalia like jingles, sinew and fringe.

“The punching bag was a lifesaver for me in the sense that it was able to, as a format and materials, encompass the narrative for the first time. This idea of adornment and regalia defused the violence of a punching bag. Where it coincided is that these traditional people were wearing garments that they made, that identified them as different from the mainstream. They felt very proud, they carried their history with them and they had happiness and sadness. There was something about it that I thought was different from fashion, it is a garment that really signifies your identity and it’s a garment that indicates that you are working and moving through the world differently. It also commanded respect. Ultimately this all melded together into the bags. Once the bags started, I started looking at all sorts of different tribal aesthetics. The powwow is an intertribal event. It’s an event where the dancers, although they are relative to tradition, they are encouraged to innovate, they are encouraged to individuate themselves and there are lots of different modern innovations that happen.”

The lyrics and wordplay aren’t limited to the punching bags. In fact, Jeffery repurposed a number of traditional wool blankets into contemporary art that hang on the wall of the museum and garner a lot of attention from local art enthusiasts. Memorable lines from ‘Time (Clock of the Heart)’ by the Culture Club, ‘Fight the Power’ by Public Enemy as well as a quote by writer James A. Baldwin are spelled out in glass beads on the blankets. SAM also displayed a number of Jeffrey’s geometrical paintings which he constructed on rawhide as well as sculpted figurines that don traditional regalia, such as jingle dresses and shawls.

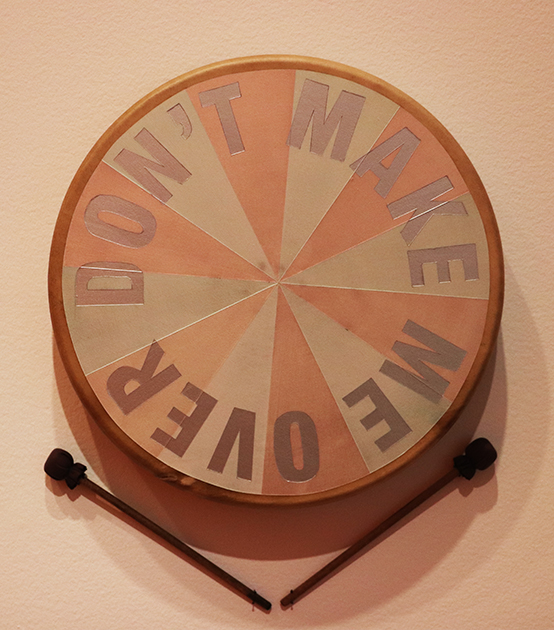

The exhibit ends in a room with rainbow curtains covered with bold letters that read ‘Don’t Make Me Over’ and ‘Accept Me for What I Am’. Projected on the wall is a video presentation by Jeffrey in which he is dressed in customized ceremonial garb and performing spoken word and song on a traditional hand drum.

Although, the Like A Hammer exhibit displays artwork that explores the identity of Jeffery Gibson as a proud queer Indigenous creative, his intention behind his work is the hope that others can identify with the art, whether through triumph or struggle, and find a sense of community as well as inspire the next generations to come to simply be themselves.

“Indigenous history and crafts provides this incredible infinite use of materials and content that I really feel privileged to have access to. When I decided to start making again, I was determined to make what I wanted to see. I started to use the word maker because it allowed me to go into everything from garments, to video, to sculptures; embrace textiles, and adornment and the decorative without feeling the boundary of what art is perceived to be. I look for words that I imagine a viewer can actually place themselves in. I move forward as an artist on the trust that we all share a similar experience. Ultimately everyone is at an intersection of multiple cultures, times, histories. The world is shifting and changing and if you’re engaged in the world, you are also shifting and changing.”

Like A Hammer is a must-see-in-person exhibit and is currently on display until May 12. For tickets and more info, please contact the Seattle Art Museum at (206) 625-8900 or visit www.SeattleArtMuseum.org.