Katie Campbell, KCTS9

PORT ANGELES, Wash. — Anne Shaffer sits on the sandy shoreline of the Elwha River and looks around in amazement. Just two years ago, this area would have been under about 20 feet of water.

So far about 3 million cubic yards of sediment — enough to fill about 300,000 dump trucks — has been released from the giant bathtubs of sediment that formed behind the two hydroelectric dams upstream. And that’s only 16 percent of what’s expected to be delivered downstream in the next five years.

All of that sediment is already reshaping the mouth of the Elwha, which empties into the Strait of Juan de Fuca on the northern shore of Washington’s Olympic Peninsula.

The depth at the mouth of the river has changed by about 50 feet. Long, charcoal-colored sandy beaches have formed where there once only smooth, platter-sized cobblestones.

Watch video report:

“This place is like Christmas,” says Shaffer, a marine biologist and the executive director of the Coastal Watershed Institute. “Everyday you come out here and its something new.”

Shaffer is leading a team of researchers who are studying the Elwha’s nearshore area, where the river’s freshwater meets the saltwater tides. Shaffer explains that until recently this area was starved of sediment, and now a whole new ecosystem is forming. Her team is trying to find out what tiny creatures are moving in.

They’re searching for evidence that species like sand lance and surf smelt are using this area as spawning grounds. These tiny fish are a common food sources for juvenile salmon.

Sand lance (top) and surf smelt (bottom) by David Ayers/USGS.

Sand lance (top) and surf smelt (bottom) by David Ayers/USGS.

Sand lance, she explained, require a very fine grain sediment in order to lay their eggs.

“We now are surrounded by the exact grain size that sand lance need to spawn,” she says.

The team scoops up bags of sand to test in the lab. So far they haven’t found evidence of sand lance spawning in this new habitat, Shaffer says. But they have found that surf smelt are spawning in areas where sandy substrate has built up.

During recent fish census surveys of the Elwha’s estuary, Shaffer’s team counted baby chum salmon in numbers they haven’t seen in years, if ever, Shaffer said. And they’ve also found a number of eulachon, a type of smelt that was once an abundant food source for coastal tribes. The eulachon is now listed as threatened under the Endangered Species Act.

“As soon as this habitat is available, these fish are using it,” Shaffer says. “None of us anticipated how quickly it would occur. I’d never seen a eulachon in the estuary before, but in the last three months, every time we survey, we see them.”

The drone of a single-engine plane causes Shaffer to look up and shield her eyes.

“I bet that’s Tom,” she says with a smile.

A Bird’s Eye View

Port Angeles pilot and photographer Tom Roorda has had one of the most unique perspectives during the last two and a half years while the dams have been slowly dismantled. He started taking land-survey photos of the Elwha eight years ago. Back then his photos were used to help the federal Bureau of Reclamation prepare for dam removal.

Today his jaw-dropping aerial photos capture the giant plume of sediment flowing out of the mouth of the Elwha.

“Until I started taking these pictures, no one had any idea how much sediment was coming down or how far it extended out into the strait,” Roorda said.

The flush of sediment has moved the mouth of the Elwha north by about 300 feet, creating a long skinny spit that extends into the Strait of Juan de Fuca. The area that used to serve as the Elwha’s estuary has been inundated with freshwater and a new estuary is forming downstream.

“As soon as it starts to rain that sediment gets washed down into the river and we get these big gulps of sediment coming down,” Roorda said.

This winter’s rains have continued to flush sediment downstream, so much so that the river’s flow is currently 10 times higher than normal. While all that sediment is ideal for building nearshore habitat, some worry the water will be too murky for salmon. Sediment can clog and irritate their gills and make it difficult to find food.

But Shaffer for one, isn’t concerned.

“Salmon are brilliant,” she said. “They have evolved over millenia. If they’re given a chance to acclimate to it, they will.”

The First Leap?

Today the entire length of Elwha looks like a free-flowing river. That’s because recent storms have submerged the remaining 25 or so feet of the Glines Canyon Dam.

Glines Canyon Dam, March 10, 2014, Olympic National Park

Glines Canyon Dam, March 10, 2014, Olympic National Park

From webcam images, it’s difficult to even identify the slope of what remains of the 210-foot spillway. This is causing some to wonder how much longer it will be before the first fish leap over the concrete barrier that remains.

It may take weeks or months, but when the first leap happens, it’s not likely to be a salmon.

“Steelhead are quite the athletes. A steelhead can leap up to 12 feet in a single jump,” said John McMillan, a NOAA biologist who is tracking fish recovery on the Elwha.

McMillan is betting on steelhead — trout that, like salmon, are born in freshwater streams before migrate to marine waters. He says he’s seen steelhead ascend a 35-foot cascading waterfall by taking a series of long leaps.

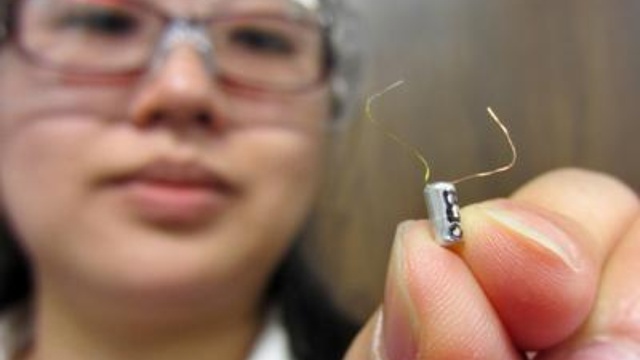

Researchers are using imaging sonar to track the different fish returning to the Elwha, and they’ve found that some steelhead have already returned to the lower Elwha, McMillan said. The bulk of the run, however, is expected to take place from April to early July, he said.

Dam deconstruction will pause May 1 to minimize disruption to the steelhead spawning season.

Removal of the Lower Elwha Dam finished in March 2012. The last of the rubble of the Glines Canyon dam is expected to be gone by September 2014.