Jack and Susan Lake, who support the water bill, at their potato farm on the Flathead Reservation. Mr. Lake’s family moved there from Idaho in 1934.

By Jack Healy, The New York Times, April 21, 2013

RONAN, Mont. — In a place where the lives and histories of Indian tribes and white settlers intertwine like mingling mountain streams, a bitter battle has erupted on this land over the rivers running through it.

A water war is roiling the Flathead Indian Reservation here in western Montana, and it stretches from farms, ranches and mountains to the highest levels of state government, cracking open old divisions between the tribes and descendants of homesteaders who were part of a government-led land rush into Indian country a century ago.

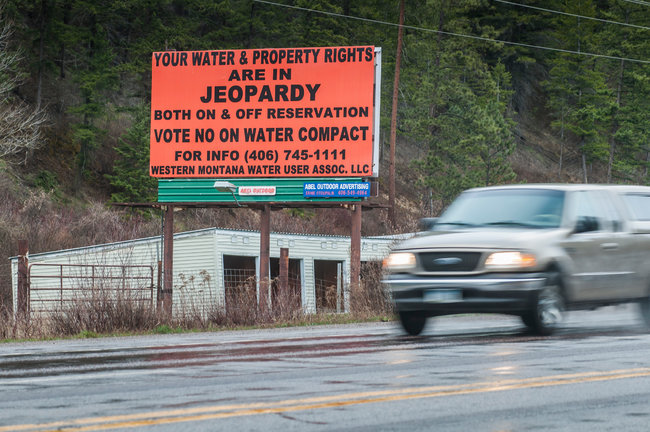

A billboard at an entrance to the Flathead Reservation in western Montana, where a bitter dispute has divided the residents.

“Generations of misunderstanding have come to a head,” said Robert McDonald, the communications director for the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes. “It’s starting to tear the fabric of our community apart.”

Dependable water supplies mean the difference between dead fields and a full harvest throughout the arid West, and the Flathead is no exception. Snowmelt flows down from the ragged peaks to irrigate fields of potatoes and wheat. It feeds thirsty cantaloupes and honeydew melons. Cutthroat trout splash in the rivers. Elk drink from the streams.

So when the government and the reservation’s tribal leaders devised an agreement that would specify who was entitled to the water, and how much they could take from the reservoirs and ditches, there was bound to be some discord. But few people expected this.

There have been accusations of racism and sweetheart deals, secret meetings and influence-peddling in Helena, the state capital. Lawsuits have been threatened. Competing Web sites have sprung up. Some farmers have refused to sell oats to those on the other side of the argument.

For months, local newspapers have published letters from people who support the water deal — known as a compact — and from opponents who see it as a power play by the tribes to seize a scarce and precious resource from largely non-Indian farmers and water users.

The proposed compact is 1,400 pages long, a decade in the making and bewilderingly complex. Essentially, it helps to lay out the water rights of the tribe and water users like farmers and ranchers. It provides $55 million in state money to upgrade the reservation’s water systems. And it settles questions about water claims that go back to 1855, when the government guaranteed the tribes wide-reaching fishing rights across much of western Montana.

The tribes say they have given up claims to millions of gallons of water to reach the deal. They say it is the only way to avoid expensive legal battles that could tie up the state’s western water resources in court for decades to come.

But the deal has rankled farmers and ranchers on the reservation, who fear they could lose half the water they need to grow wheat and hay and to water their cattle. Under the compact, each year farmers and ranchers would get 456,400 gallons of water for every acre they irrigate. Tribal officials say that is more than enough, but farmers say the sandy soil is just too thirsty. They fear they will be left dry.

“They’ve literally thrown us under the bus, and we’ve had to fight this thing ourselves,” said Jerry Laskody, who has joined a group of farmers and ranchers in opposing any deal. The group has held meetings and taken out advertisements to spread the word.

As visitors drive onto the reservation, a bright orange billboard declares, “Your Water & Property Rights Are in Jeopardy.” The pact has also angered some conservative residents around the valley, who accuse the tribe and Montana officials of colluding in what they characterize as legalized theft.

“There’s a lot of coercion, a lot of threats,” said Michael Gale, who retired here looking for beauty, and has spent hundreds of hours attending meetings, writing letters and poring over documents in the hope of killing the compact. “Like they always say: Whiskey’s for drinking. Water’s for fighting.”

At the heart of the dispute is a question that has haunted the United States’ relations with indigenous people for centuries and provoked countless killings, dislocations, treaties and court battles: Who has a claim to the land and its resources?

It is an emotional issue, especially here.

In the early 1900s, the federal government opened up millions of acres on the Flathead and other reservations to white homesteaders, a decision that echoes today across the Great Plains and the West. Tribal members were allotted specific parcels, and the rest was put up for sale. Homesteaders came in droves, to stake farms, open sawmills and grocery stores, plant wheat and build roads.

Within a decade, settlers outnumbered tribal members on the Flathead. Today, resorts and million-dollar homes line the shores of Flathead Lake, the reservation’s largest body of water. Of the reservation’s more than 28,000 residents, about 7,000 are American Indians, according to census data.

“We are minorities on our homeland,” said Mr. McDonald, the communications director.

Over the years, tribal members married homesteaders’ children. Families blended. Children from Salish and Kootenai families attended the same schools as those who had moved in from Missoula or Washington State. Residents say that today, the bonds and friendships are wide and deep.

Until they are not. A report by the Montana Human Rights Network once described the reservation as home to “the most aggressive anti-Indian activity in Montana” because of its patchwork settlement. Conflicts have flared over tribal control of a major dam on Flathead Lake, and over whether tribal police officers should be able to arrest or detain non-Indians on the reservation. In the late 1980s, a dispute over hunting and fishing regulations led to screaming matches and death threats.

“They painted their fence posts orange and let it be known they’d shoot you if you walked on their land,” said Joe McDonald, who for nearly three decades was the president of Salish Kootenai College here on the reservation.

This time, the fight appears bound for court. After years of public meetings and deliberation, the full compact finally arrived in the Montana State Capitol this spring. It was supported by the state’s first-term governor, Steve Bullock, a Democrat, as well as by some Republican lawmakers from the area. But with farmers showing up to denounce the compact measure, the Republican-led Legislature killed the bill.

For Susan and Jack Lake, that decision cast a shadow over their potatoes. Mr. Lake’s family moved here from Idaho in 1934. Today, the family farms 1,000 acres, 85 percent of it irrigated. They grow seed potatoes that are ultimately used to make chips and instant mashed potatoes.

The Lakes agonized over the water deal, but eventually decided to support it. They worried about losing water, but said that going to court against a tribe with older, stronger claims to the reservation’s water supplies felt like a suicide mission.

Sometimes, Ms. Lake said, it just felt absurd: so many years of tangled fights over something so simple and pure.

“It’s beautiful,” she said. “You turn it on and make things grow.”