By Wade Sheldon, Tulalip News

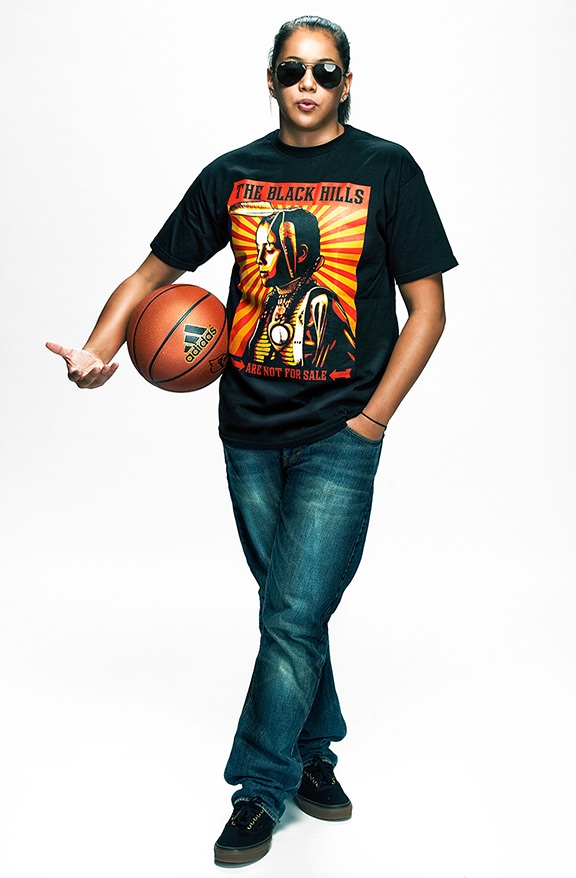

Growing up on the rez, basketball is more than just a game—it’s woven into our culture. From broken-down hoops in backyards to the pristine hardwood of tribal gymnasiums, rez rats are always ready. You’ll spot them with shorts on under their pants, prepared for a pickup game or to jump in for a tournament. Always in the gym, with a ball in hand, dribbling away the troubles of the world, they live for the game and its escape.

If that sounds familiar, Netfix’s Rez Ball might make for the perfect watch for you and your family, especially if you have a few rez rats under your roof. The story follows a high school basketball team from Chuska, New Mexico, as they try to come together after the tragic loss of one of their teammates. The team faces adversity on and off the court, navigating the challenges of rez life through hardship, unity, and their shared love for the game, all while striving for victory.

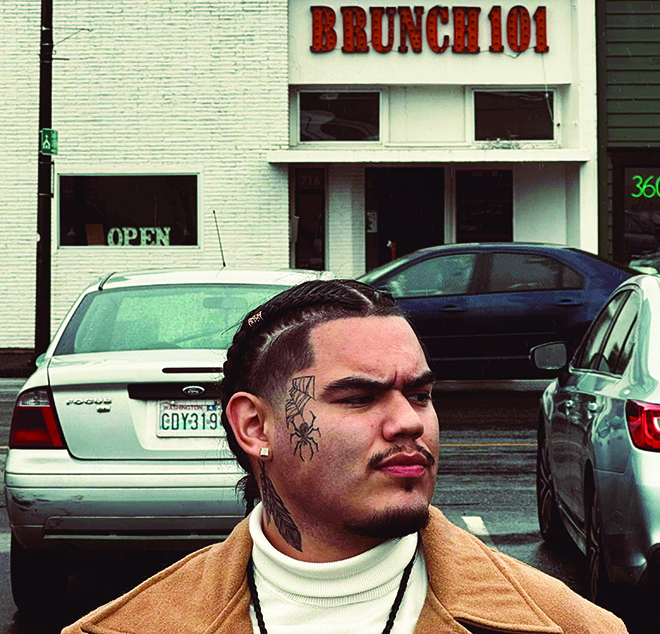

Recently, Tulalip News sat down with one of the stars of Rez Ball, the Pacific Northwest’s own Damian Henry Castellane, who plays Ruckas Largo. Castellane, enrolled in the Puyallup Tribe but raised on the Squaxin Island Reservation in Washington’s Mason County, shared insights into his journey to becoming part of the film.

When asked about his connection to basketball, Damian shared, “I started playing reservation basketball at about five years old. I’ve only played in tournaments and never played school ball. For us rez kids, basketball is all we have. It’s the only way we know to escape our home and school lives. Growing up, my uncles were excellent basketball players, and I was always encouraged to pick up where they left off, so I just had to take it there.”

The conversation then turned to how Castellane landed his role in Rez Ball. He recounted, “I like to tell this story because it encourages people to take risks. My good friend Thomas sent me a casting call he found on Facebook for a Netflix movie produced by LeBron James. I laughed and thought, ‘They’re not going to pick me; I’m from Squaxin.’ But he insisted I give it a shot. I submitted my name, and they called me for a video audition. They liked my look — the tattoos, the hair — and asked me to read for the role. I set my phone up, had my girlfriend read the other lines, and sent it in. They loved my humor and invited me to audition in person in Albuquerque. There were 5,000 auditions for Rez Ball, and I felt honored to be picked from such a large pool. I performed well in both the basketball and acting sides of the audition. Two days later, they called to offer me the role of Ruckas Largo and asked me to fly out in four days. I stayed for two months, and the rest is history.”

When asked what it meant for him to be part of the film, Damian said, “It meant everything because I feel like I was doing it for Indian Country. Basketball is so meaningful and powerful to me. What better film to be a part of than Rez Ball? I can’t express enough how grateful I am for this opportunity.”

Castellane also spoke about how his community has responded to his success. “What’s funny is that on the Squaxin Reservation, people still treat me like the same person I was before. They don’t see me as a Netflix star, which I love. I can walk into the tribal store, and it feels like home. However, when I go outside my reservation, such as to the Puyallup area, I can’t go into stores or casinos without being recognized. It’s picture after picture in those places, but I appreciate that my reservation treats me like I’m still just me.”

In today’s era, shows like FX’s award-winning Reservation Dogs offer hope to Indigenous youth. Many of us grew up without seeing anyone who looked like us in movies. All we had were films like Dances with Wolves and Smoke Signals. But now, shows like Reservation Dogs have paved the way for Native representation in Hollywood. “Now we see people who act and look just like us,” Castellane said. “I believe Native cinema is opening doors for many young Indigenous individuals, and I’m proud to be a part of it.”

Damian shared his childhood dream of acting: “Since I was a kid, I would tell my mom, ‘I’m going to be on TV one day, Mom. I’m going to go to Hollywood!’ She always supported me, saying, ‘I believe you, son.’ Growing up, I’d tell my friends I wanted to be in movies or become one of the biggest rappers of all time, and they would laugh at me, saying things like, ‘Yeah, right. Pick a different dream.’ So finally achieving this dream by being in the film has been the best experience ever. I’m a humble person, and I’m just proud of myself.”

One of Castellane’s favorite memories from filming was a lighthearted moment involving sheep herding. “During the scene where we were herding sheep, it was real—we were actually pushing those sheep to the pen. There was this one timid sheep that was hyper. A background character named Cooper is in the movie, and that sheep managed to juke him out, causing him to fall. I hoped that would make it into the film, but it didn’t. It was a funny moment that everyone on set still talks about.”

Regarding the heavier themes in the movie, including struggles with suicide and addiction, Damian said, “I can relate a lot. In Indian Country, issues like drug abuse, alcohol abuse, and suicide are significant concerns. If you haven’t experienced it personally, you’ve likely seen it firsthand through family, friends, or in your community. For example, when I was 13, my aunt Jamie committed suicide. The film addresses suicide—like the character Nataani taking his life—which brought back memories for me. I also connected with Jimmy, who tells his mom he’ll get her beer money. I had a neighbor growing up who struggled with alcohol, so that resonated with me.”

As the interview concluded, Castellane urged, “I encourage everyone to watch the film. If you need to, watch it again because it’s truly an amazing movie. The whole cast and crew of Rez Ball would appreciate your support as we aim to win awards with this film.”

As for his future, Damian teased exciting projects ahead. “Whether in music or acting, I want to take everything as far as possible. I have a big acting gig coming up that I can’t discuss yet, but it’s exciting. I also recently dropped an album titled AJ’s World, dedicated to my little brother, who passed away on March 9. You can find it on all platforms—Apple Music, Spotify, iHeartRadio, YouTube, and more.”

Damian Henry Castellane’s path from reservation basketball courts to the big screen is a quiet reminder of the power of pursuing one’s passion. You can catch his work in Rez Ball, which is now streaming on Netflix.

November 7, 2013

November 7, 2013