By Eugene Volkh | May 15, 2:14 p.m.

“Group libel” lawsuits claiming that a race, ethnic group, religion, and the like was libeled by knowing or reckless falsehoods about them aren’t allowed under modern American libel law. But the matter is different when the group is small enough; in the words of the Restatement (Second) of Torts,

One who publishes defamatory matter concerning a group or class of persons is subject to liability to an individual member of it if, but only if,

(a) the group or class is so small that the matter can reasonably be understood to refer to the member, or

(b) the circumstances of publication reasonably give rise to the conclusion that there is particular reference to the member….

Comment a. As a general rule no action lies for the publication of defamatory words concerning a large group or class of persons. Unless the group itself is an unincorporated association, as to which see § 562, it cannot maintain the action; and no individual member of the group can recover for such broad and general defamation. The words are not reasonably understood to have any personal application to any individual unless there are circumstances that give them such an application. The extreme example is the statement of David that “All men are liars,” which in a sense defames all mankind and yet could not reasonably be taken to have any personal reference to each member of the human race. On the same basis, the statement that “All lawyers are shysters,” or that all of a great many persons engaged in a particular trade or business or those of a particular race or creed are dishonest cannot ordinarily be taken to have personal reference to any of the class.

Illustrations:

1. A newspaper publishes the statement that the “Stivers clan” have been engaged for years in a feud in the course of which many murders have been committed. There are in the community a great many interrelated families named Stivers. Neither the entire group nor any member of it can recover for defamation.

2. A newspaper publishes the statement that the officials of a labor organization are engaged in subversive activities. There are 162 officials. Neither the entire group nor any one of them can recover for defamation.

b. When the group or class defamed is sufficiently small, the words may reasonably be understood to have personal reference and application to any member of it, so that he is defamed as an individual. In this case he can recover for defamation. Thus the statement that “That jury was bribed” may reasonably be understood to mean that each of the twelve jurymen has accepted a bribe. It is not possible to set definite limits as to the size of the group or class, but the cases in which recovery has been allowed usually have involved numbers of 25 or fewer.

Illustration:

3. A newspaper publishes a statement that the officers of a corporation have embezzled its funds. There are only four officers. Each of them can be found to be defamed.

The core issue is thus whether a statement about a group is seen as a statement “of and concerning” the particular plaintiff — the general view is that statements about large groups aren’t so seen (because listeners recognize that generalizations about a group often don’t apply to individual members), but statements about small groups might be so seen.

This is the very issue that came up in Wednesday’s federal trial court decision inDegroat v. Cooper (D.N.J. May 14, 2014). Eriq Gardner (Hollywood Reporter) has the background:

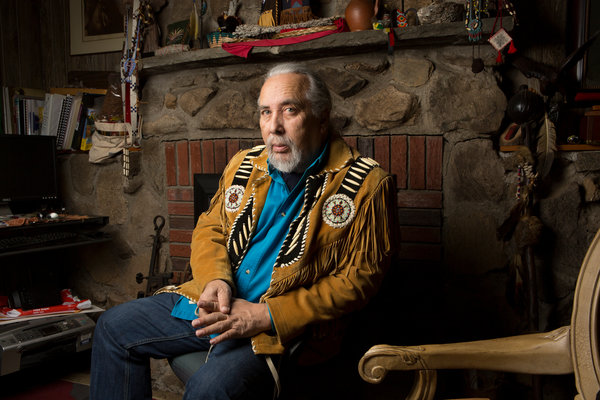

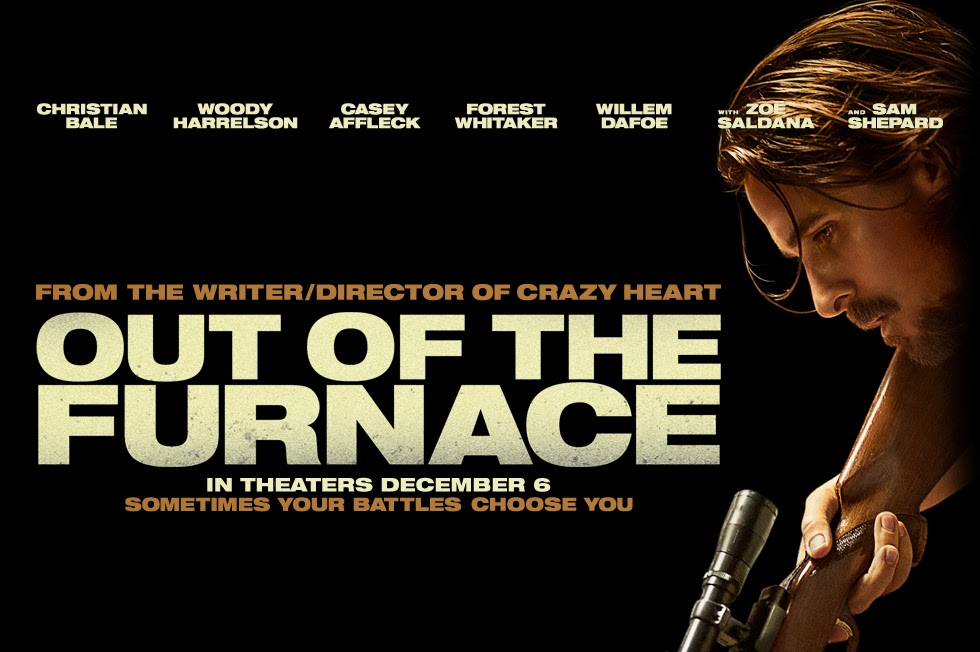

A New Jersey federal judge has dismissed a defamation lawsuit over Out of the Furnace filed last December by 17 members of the Ramapough Lunaape Nation, a Native American tribe located mostly in the mid-Atlantic region of the U.S.

The film starred Christian Bale tracking his younger brother, played by Casey Affleck, who has been lured into a ruthless crime ring led by the evil character of Harlan De Groat, played by Woody Harrelson. The group is identified as the Jackson Whites and described as a community of “inbreds.” …

Note that the movie didn’t just refer to the group, but to at least one common surname (De Groat) within the group. Still, the court held, this wasn’t enough to make the statements “of and concerning” the plaintiffs:

Plaintiffs plead only that some of them share the same surname, but not first name, as two of the characters in the movie. They also contend that they are Ramapoughs, as are the characters in the movie, and that many of them live in the same region as the Ramapoughs. These allegations do not suffice to show that the alleged defamatory statements are “of and concerning” these Plaintiffs. In fact, Plaintiffs concede in their brief that the statements they complain of do not refer to them: “It is acknowledged that these Plaintiffs are not, specifically, characters in the movie ….”

There is of course, another issue here: The film wasn’t a documentary, and reasonable viewers would perceive it as a work of fiction. And while sometimes a work that is obviously “roman à clef” — i.e., is perceived by the public as making claims about real events, though under a fictionalized veneer or with some fictional components — might be seen as libelous, that would be a pretty high bar to pass, given viewers’ understanding that movies that aren’t sold as documentaries are generally about storytelling, not about factual accuracy (even when they are to some extent based on real surroundings). Still, the court managed to largely avoid this issue by simply concluding that the movie couldn’t be seen as making factual claims of and concerning any particular individual, whether or not it would be seen as making factual claims about the large group.