Hundreds gather for 4th Annual Unis’tot’en Action Camp against pipelines in ‘BC’

By Aaron Lakoff, Vancouver Media Co-op

From July 10th to 14th, roughly 200 Indigenous and non-Indigenous people gathered in unceded Wet’suwet’en territory in central British Columbia for the 4th Annual Unis’tot’en Action Camp. The Unis’tot’en clan of the Wet’suwet’en First Nation have maintained a blockade on the only bridge leading into their territory since July 2010 in an attempt to keep seven proposed oil and gas pipelines off their traditional lands. The pipelines would carry shale gas obtained through fracking, or bitumen oil from the Alberta tar sands, to the Pacific coast, where it would be exported on mega-tankers towards Asian markets

The action camp brings supporters of the Unis’tot’en to the blockade site in order to learn about the struggle, to network, and to bring action ideas back to their own communities.

Toghestiy, Hereditary Chief of the Likhts’amisyu Clan of the Wet’suwet’en nation, said he was very happy with the high proportion of Indigenous participants at this year’s camp compared to previous years.

“I would say about 40% of the population of the action camp was Indigenous, and they were Indigenous from different parts of Turtle Island,” Toghestiy told the Vancouver Media Co-op (VMC). “So it was amazing to have all these grassroots Indigenous people come together in solidarity with one another. We created an alliance, and it was a pretty beautiful experience. It will help us fulfill our responsibility [to the land] into the future.”

While most participants at the camp hailed from Vancouver and Victoria, people also travelled from as far away as California, New Mexico, and Toronto to lend their support. Amber Nitchman travelled up to the Unis’tot’en Action Camp from Lancaster, Pennsylvania.

“I want to support Indigenous rights and sovereignty everywhere, especially those who are opposing extractive industries,” Nitchman told the VMC while on a night-time security shift at the blockade site. At home, she is involved with anti-coal mining campaigns. “Some of the pipelines [here] are for the same industry, and it’s the land and water being destroyed in both places for profit, and destroying what little is left that people are able to live on in a sustainable way.”

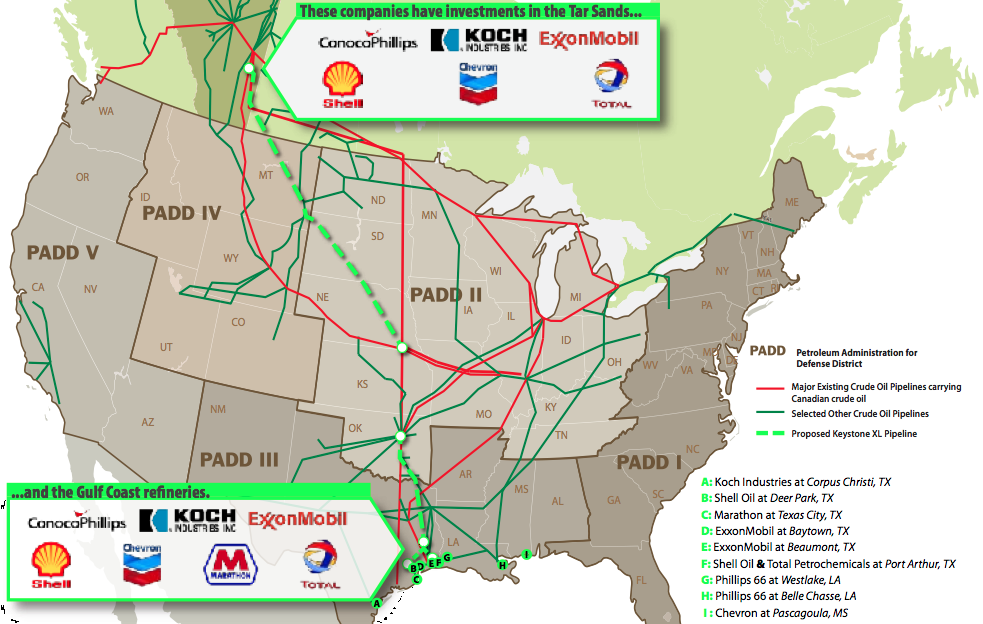

Wet’suwet’en territory is located about 1000 km north of Vancouver. It lies on what has been described as Canada’s “carbon corridor,” a geographically strategic region where major oil companies such as Chevron and Exxon are seeking to connect the Alberta tar sands to the Pacific coast for export. The Unis’tot’en claim that these pipelines, requiring clear cutting and prone to leaks and spills, would threaten watersheds, forests, rivers, and salmon spawning channels—source of their primary staple food.

Some of proposed pipelines on Wet’suwet’en territory are intended to carry natural gas from hydraulic fracturing (or “fracking”) sites near Fort Nelson, BC, close to the border of the Northwest Territories. Wet’suwet’en activists are concerned not only for their own community, but also for communities at tar sands and fracking extraction sites.

“In those territories, those people are suffering from decimated water,” said Mel Bazil, a Wet’suwet’en and Gitxsan activist who has been helping out with the Unis’tot’en blockade. “They have no clean drinking water left in their territories. All of their right to clean drinking water is delivered to them by truck. They allowed their responsibility to clean drinking water that already exists in their territories to be diminished, and in place of that, now they have the right of clean water being delivered to them.”

Water is central to this struggle. The pristine Morice River flows through Wet’suwet’en territory, and is still clean enough to drink and fish from. For contrast, local people often reference Michigan’s Kalamazoo River, devastated by the largest inland oil spill in U.S. history when an Enbridge tar sands pipeline burst in 2010.

At the action camp, Unis’tot’en clan members declared Wet’suwet’en territory to be the epicentre for struggles against the tar sands. The Alberta tar sands are the largest industrial project on Earth and the tar sands mining procedure is hugely energy-intensive. Extraction at the tar sands releases at least three times the amount of carbon dioxide as regular crude oil extraction, and uses five barrels of fresh water to produce a single barrel of oil, according to the activist research group Oil Sands Truth.

“My people have been on these territories for thousands of years, until about 100 years ago when the government forced our people off these lands and put them in reservations,” said Freda Huson, the spokesperson for the Unis’tot’en camp, in an interview under the food supplies tent. “And probably just about four years ago, my generation has stood up and said, ‘No more.’

“There’s too much destruction happening out here, because we grew up on these lands, coming out here all the time. And every time we came out here we saw more and more destruction. So we sat down with our chiefs and said, ‘We can’t just sit by any more and let them keep destroying the lands.’ There will be nothing left for our children and grandchildren and great-grandchildren. We found out about the pipelines and which route they were planning to go.”

In May, the BC provincial government officially opposed one of the proposed pipeline projects on Wet’suwet’en territory, the Enbridge Northern Gateway. Premier Christy Clark cited environmental safety concerns. But Huson was skeptical.

“To me they’re just all talk. I don’t believe anything the government says,” retorted Huson. “They make all these empty promises, and they do exactly the opposite of what they say. Based on how Christy Clark has been talking pro-pipelines, that this is going to get them out of deficit, because we know for a fact that the BC government is in a huge deficit.”

Indigenous people from different nations across ‘Canada’ came to the Unis’tot’en camp to make links between struggles against oil and gas pipelines. One of them was Vanessa Grey, a 21-year old activist from the Aamjiwnaang First Nation reserve in southern Ontario.

Aamjiwnaang sits on the pathway of Enbridge’s Line 9 project, which will carry tar sands bitumen eastward towards Maine. Demonstrators have attempted to stop the project through a variety of direct actions, including a five-day occupation of an Enbridge pumping station near Hamilton, Ontario, this past June.

“I feel that there’s a lot here that someone like myself or the youth who have come here can really learn from,” said Grey, sitting in a forest clearing near the Morice River. “Where we come from, the land has already been destroyed and we already see the effects. Here, they are trying to save what’s left of it, and we’re able to see what could have been without the industry.”

During the five days of the camp, participants attended action planning sessions and workshops on a variety of subjects, including decolonization, movement building, and the Quebec student strike. Participants also had the chance to help construct a permaculture garden and pit-house directly on the route of the Enbridge Northern Gateway pipeline.

On July 20, just days after the action camp had ended and all of the participants had returned home, a helicopter carrying pipeline surveyors was discovered on Unis’tot’en territory, behind the blockade. The workers were quickly confronted by Chief Toghestiy and were forced to leave.

“We were busy that day working on salmon that day, and locating berry patches to start harvesting for winter. Then all of the sudden we heard a helicopter fly over,” Toghestiy told the VMC over the phone.

Helicopters flying overhead is a common occurrence around the Unis’tot’en territory, but something seemed wrong about this one to Toghestiy. “This one sounded like it was slowing down, and you could hear the rotors ‘whoop-whooping’ really loud. I thought to myself, ‘This helicopter might be landing.’” Toghestiy and a supporter of the camp who was on the scene immediately drove down the road in the direction of the helicopter, and discovered it had landed not far away.

According to Toghestiy, the workers were wearing hard-hats, reflector vests, and had clipboards with them. When confronted, they confirmed that they were pipeline workers, but didn’t know that they had infringed on an Indigenous blockade site. “I told them ‘bullshit! Your company knows [about the blockade]!” said Toghestiy as he recounted the situation.

After he yelled at them to leave, they quickly got back in the helicopter and the pilot restarted the motor and took off. “As they were flying away, the helicopter pilot assured me that they wouldn’t come back, and so did the workers.”

Toghestiy said the workers did not reveal which company they were with, but he observed that “they were standing in the … proposed new alternative route of the Pacific Trails pipeline project.”

The helicopter visit was not the first infringement by pipeline companies onto sovereign Wet’suwet’en territory. In November 2012, surveyors were also found behind the blockade lines, and were issued an eagle feather, which is a Wet’suwet’en symbol for trespassing.

Toghestiy said that expelling these unwelcome workers from unceded Indigenous lands also has a deeper meaning. “We’re stopping the continued delusion that the government is putting out there that they still have right to give out licenses or permits on lands that were never ceded by the Indigenous people. There is no bill of sale that has ever been produced that says they have the right to do that,” he said.

Huson added that if a helicopter is discovered again on her territory, the company’s actions will have more severe consequences. “I’m planning to draft a letter to the helicopter company and other companies working for Apache right now, saying, ‘You’ve received your final warning, and if any more choppers or equipment comes across the blockade again, we’ll confiscate whatever comes in, and workers will be walking out,’” she said in a stern but calm voice.

Indigenous delegates at the camp decided to hold a Day of Action against extractive industries on August 14, 2013, and fundraising is already underway to support the blockade throughout the winter. Meanwhile, Toghestiy and Huson expect even more people to come up for the action camp in the summer of 2014.

For more information about the August 14th Day of Action and next year’s action camp, visit: www.unistotencamp.com or their Facebook page.

Click here for full audio interviews and a photo essay from the camp.

Aaron Lakoff is a radio journalist, DJ, and community organizer living in Montreal, trying to map the constellations between reggae, soul, and a liberated world. This article was made possible with support from the Vancouver Media Co-op.