The ancestral connections of tribal coastal communities to the ocean’s natural resources stretch back thousands of years. But growing acidification is changing oceanic conditions, putting the cultural and economic reliance of coastal tribes—a critical definition of who they are—at risk.

It’s a big challenge to tribes in the Pacific Northwest, said Billy Frank Jr. (Suquamish) back in 2010, addressing the 20 tribes that make up the Northwest Indian Fisheries Commission.

“It’s scary,” he said in a video posted at the fisheries commission website. “The State of Washington hasn’t been managing it. The federal government hasn’t been managing it. We’ve got to bring the science people in to tell them what we’re talking about.”

What they were talking about are the decreases in pH and lower calcium carbonate saturation in surface waters, which together is called ocean acidification, as defined by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). Some 30 percent of the carbon, or CO2, released into the atmosphere by human activities has dissolved straight into the sea. There it forms the carbolic acid that depletes ocean waters of the calcium that shellfish, coral and small creatures need to make their calcium carbonate shells and skeletons.

Its impacts are felt by Native and non-Native communities in Washington State that rely on oysters and shellfish. Disastrous production failures in oyster beds caused by low pH-seawater blindsided the oyster industry in 2010, prompting a comprehensive 2012 investigation by Washington State. Earlier this month Governor Jay Inslee took the issue to the media in order to jump-start climate change action in his state, The New York Times reported on August 3.

The Quinault Indian Nation on Washington’s coast is part of one of the most productive natural areas in the world and is especially involved in the ocean acidification issue. The rivers in Quinault support runs of salmon that have in turn supported generations of Quinault people. The villages of Taholah and Queets are located at the mouth of two of those great rivers. The Pacific Ocean they flow into is the source of halibut, crab, razor clams and many other species that are part of the Quinault heritage.

“Since the summer of 2006, Quinault has documented thousands of dead fish and crab coming ashore in the late summer months, specifically onto the beaches near Taholah,” Quinault Marine Resources scientist Joe Schumacker told Indian Country Today Media Network. “Our science team has worked with NOAA scientists to confirm that these events are a result of critically low oxygen levels in this ocean area.“

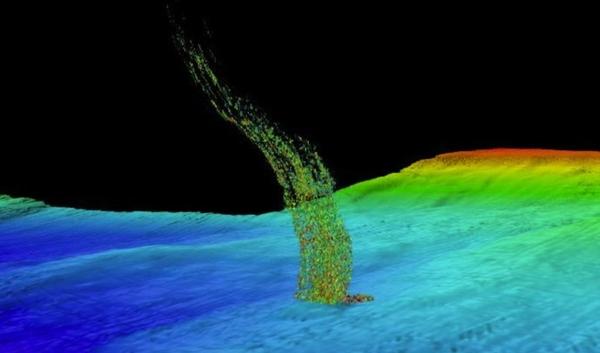

The great productivity of this northwest coast is driven by natural upwelling, in which summer winds drive deep ocean waters, rich in nutrients, to the surface, Schumacker explained. This cycle has been happening forever on the Washington coast, and the ecosystem depends on it.

But now, “due to recent changes in summer wind and current patterns possibly due to climate change, these deep waters, devoid of oxygen, are sometimes not getting mixed with air at the surface,” Schumacker said. “The deep water now comes ashore, taking over the entire water column as it does, and we find beaches littered with dead fish—and some still living—in shallow pools on the beaches, literally gasping for oxygen. Normally reclusive fish such as lingcod and greenling will be trapped in inches of water trying to get what little oxygen they can to stay alive.”

The Quinault, working with University of Washington and NOAA scientists determined these hypoxia events were also related to ocean acidification.

“Now Quinault faces the potential for not just hypoxia impacts coming each summer, but also those same waters bring low-pH acidic waters to our coast,” Schumacker said. “Upwelling is the very foundation of our coastal ecosystem, and it now carries a legacy of pollution that may be causing profound changes unknown to us as of yet. The Quinault Department of Fisheries has been seeking funding to better study and monitor these potential ecosystem impacts to allow us to prepare for an unknown future.”

Schumacker noted that tribes are in a prime position to observe and react to these changes.

“The tribes of the west coast of the U.S. are literally on the front line of ocean acidification impacts,” he said. “Oyster growers from Washington and Oregon have documented year after year of lost crops as tiny oyster larvae die from low pH water. What is going on in the ecosystem adjacent to Quinault? What other small organisms are being impacted, and how is our ecosystem reacting? We have a responsibility to know so we can plan for an uncertain future.”

Scientists from NOAA and Oregon State University studied ocean waters off California, Oregon and Washington shorelines in August 2011, and found the first evidence that increasing acidity was dissolving the shells of a key species of minuscule floating snails called pterapods that lie at the base of the food chain.

Their study, published in the April 4, 2014, edition of the British scientific journal Proceedings of the Royal Society B, found that 53 percent of pterapods “are already dissolving,” said NOAA’s Feely.

“Pteropods are only a canary in this coal mine,” the Quinault’s Schumacker said. “They are a critical component of salmon diets, but what other creatures in the ecosystem are being affected?”

It’s a concern too, for the Yurok Tribe on the northern California coast. Micah Gibson, director of the Yurok Tribe Environmental Program, told ICTMN, “We’ve done some research, but no monitoring yet.”

The Passamaquoddy Tribal Environmental Department in Maine is monitoring ocean acidification, according to a letter the tribe sent to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). They reported that the pH of Passamaquoddy, Cobscook Bays and the Bay of Fundy was around 8.03 during the 1990s and had dropped to 7.92.

The lower the pH value, the more acidic the environment. If, or when, the Passamaquoddy letter stated, the level in bays falls to 7.90, shellfish—including clams, scallops and lobster, all economic mainstays—will die.

In Alaska, coastal waters are particularly vulnerable because colder water absorbs more carbon dioxide, and the Arctic’s unique ocean circulation patterns bring naturally acidic deep ocean waters to the surface, according to recent research funded by National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) awaiting publication in the journal Progress in Oceanography.

Ocean acidification spells even more trouble for the Inuit subsistence way of life.

“New NOAA-led research shows that subsistence fisheries vital to Native Alaskans and America’s commercial fisheries are at-risk from ocean acidification,” NOAA said in the report. “Emerging because the sea is absorbing increasing amounts of carbon dioxide, ocean acidification is driving fundamental chemical changes in the coastal waters of Alaska’s vulnerable southeast and southwest communities.”

The pH of the ocean’s surface waters had held stable at 8.2 for more than 600,000 years, but in the last two centuries the global average pH of the surface ocean has decreased by 0.11, dropping to 8.1. That may not sound like a lot, but as of now the oceans are 30 percent more acidic than they were at the start of the Industrial Revolution 250 years ago, according to NOAA.

If humans continue emitting CO2 at the level they are today, scientists predict that by the end of this century the ocean’s surface waters could be nearly 150 percent more acidic, resulting in a pH the oceans haven’t experienced for more than 20 million years.

The ocean acts as a carbon sink, greatly reducing the climate change impact of CO2 in the atmosphere. When scientists factor in our increasingly acidic oceans their studies show that global temperatures are set to rise rapidly, according to a study of ocean warming published last year in the journal Geophysical Research Letters.

These frightening scenarios illustrate the point made by Frank in his talk on ocean acidification: Humanity must meet this challenge. So too must Inslee’s persistence in trying to place a high priority on climate change in Washington DC.

RELATED: Obama’s Climate Change Report Lays Out Dire Scenario, Highlights Effects on Natives

We are moving into the Anthropocene Age, a new geological epoch in which humanity is influencing every aspect of the Earth on a scale akin to the great forces of nature, according to the journal Environmental Science & Technology. The Anthropocene challenges American Indians, but if traditional knowledge could foresee the tremendous challenges posed by ocean acidification, Indigenous knowledge can surely find solutions to the impacts of climate change, starting with how we use energy, and how much carbon we emit.

“Have a little courage, and get out of some boxes,” the environmentalist and writer Winona LaDuke told ICTMN. “Put in renewable energy and re-localize our economies, from food to housing, health and energy.”

Read more at http://indiancountrytodaymedianetwork.com/2014/08/14/oceans-rising-acidification-dissolves-shellfish-coastal-tribes-depend-156395?page=0%2C1