By Chris Winters, The Herald

EVERETT — Oil train explosions might grab headlines, but there are a number of other issues surrounding the shipment of fossil fuels that are bringing a diverse group of local leaders together.

SELA, the Safe Energy Leadership Alliance, is providing a forum for local leaders to work together to protect their communities from the negative effects of rising shipments of oil and coal.

More than 150 public officials are listed as members, including mayors and city council members from many Pacific Northwest cities that lie on major rail lines, such as Edmonds, Mukilteo, Everett and Marysville.

SELA’s latest meeting, the sixth since the group was established, included several tribal leaders, uniting native and non-native leaders around a common interest.

“I think this is one of the first initiatives that brings us all together,” said Tulalip Tribes Chairman Mel Sheldon Jr., who attended the Feb. 4 meeting at Everett Community College.

King County Executive Dow Constantine organized SELA a year and a half ago, and the group’s influence now extends into Oregon, Idaho, Montana and British Columbia.

A regional organization is needed to counter the power that international oil, coal and railroad companies have, he said.

“Local elected officials acting individually won’t be able to have an impact on the global or national issues,” Constantine said.

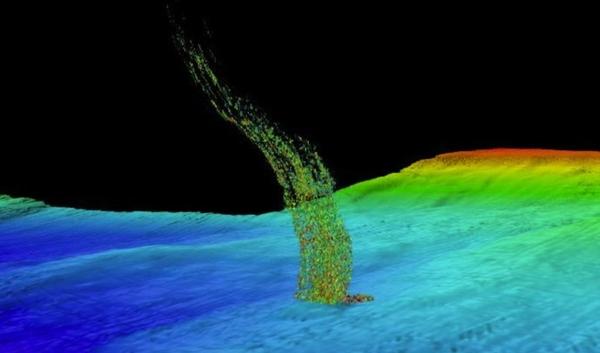

And yet, local communities bear the effects of those same industries, whether it’s the risk of oil spills or fires, coal dust blowing out of passing hoppers, or even traffic jams in cities such a Marysville with a high number of at-grade crossings.

For Tim Ballew, chairman of the Lummi Nation, the issue hit home when SSA Marine applied to build the new Gateway Pacific coal terminal at Cherry Point, close to the Lummi Reservation.

The Lummi were joined by several other tribes, including Tulalip and the Swinomish Indian Tribal Community, in opposing the project.

Ballew told the SELA attendees that effects of increased shipping on native fishing grounds as well as the development of the terminal in an area of spiritual and archaeological significance present a challenge to the tribe’s treaty rights.

“At the heart of the issue, with all of these negative impacts that will come to our community and compromise the integrity of the place we live in, the benefits won’t really go to the people,” Ballew said.

The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers is expected to issue a ruling soon on the project’s permit.

Keeping the focus on a single issue has allowed SELA to transcend partisan boundaries, too, Constantine said.

Tribes seek to protect their treaty rights, cities fear derailments and traffic blockages, and rural communities find that fossil fuels are taking up more rail capacity and squeezing out agricultural products.

One 2012 study by the Western Organization of Resource Councils predicted that rail traffic of wheat, corn and soybeans will have to compete with coal and oil for space on trains, resulting in longer delays in getting to market. There were 38.3 million tons of agricultural products shipped to Asia through Pacific Northwest terminals in 2010.

“Farming and ranching and orchards are tough enough businesses without piling on the added burden of getting goods to market,” Constantine said.

David Browneagle, vice chairman of the Spokane Tribe of Indians, pointed out that pollution ultimately doesn’t discriminate who it affects.

“Coal dust will go into all our lungs together,” Browneagle said. “It’s not going to come off the train and say ‘Hmm, that’s an Indian, so I’ll go in him.’ ”

He added his great-great grandfather tried and failed to prevent the railroads from arriving in Indian Country, but that it’s a good thing that this group was doing something now to push back.

Megan Smith, director of Climate and Energy Initiatives in Constantine’s office, has been tracking progress and the public comment windows of new terminal projects in the northwest, as well as coordinating those comments from a large number of local officials.

So far, SELA members have sponsored successful legislation in Olympia, in the form of tougher safety regulations on oil trains, as well as in Oregon, which has enacted a similar law, Smith said.

The work won’t stop at Cherry Point or with a few state laws. Another proposal, the Tesoro Savage oil terminal in Vancouver, Washington, will enter the environmental review stage possibly by the end of the year, said Beth Doglio, the campaign director of the environmental nonprofit Climate Solutions.

Tesoro Savage could become the largest terminal on the West Coast, Doglio said. The oil and coal boom is fueling interest in other projects all over the country.

“We are definitely a movement together that has been very strong, very clear in the message that this is not what we want in the state of Washington, Oregon, Idaho, Montana, and North Dakota,” Doglio said.

Tulalip Chairman Sheldon said SELA is helping different groups learn to work together and trust each other. That may lead to identifying other common interests.

“When you get leaders coming together with good issues, issues that bond us together, that to me really is the formula for success,” he said.