Four of the dirtiest plants, which sit on Native American soil, were expecting more lenient goals under the Clean Power Plan, but the EPA shifted gears.

By Naveena Sadasivam, Insideclimate News

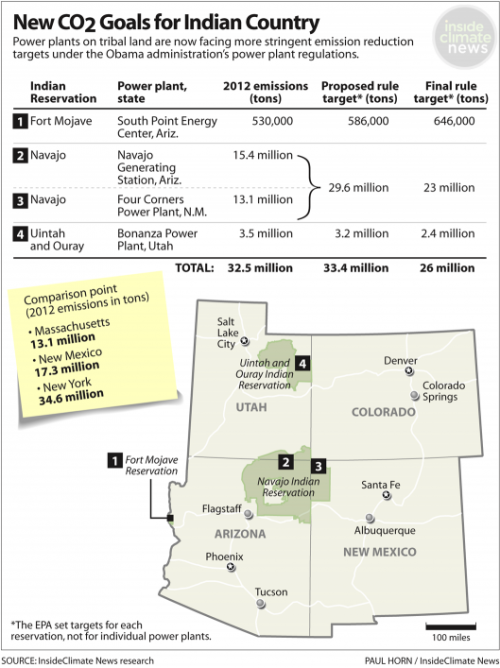

Four Western power plants that emit more carbon dioxide than the 20 fossil-fuel-fired plants in Massachusetts thought they would be getting a break under the Obama administration’s new carbon regulations––until the final rule ended up treating them just like all the other plants in the country.

The plants are located on Native American reservations, and under an earlier proposal, they were required to reduce emissions by less than 5 percent. But the final version of the rule, released earlier this month, has set a reduction target of about 20 percent.

A majority of the reductions are to come from two mammoth coal plants on the Navajo reservation in Arizona and New Mexico—the Navajo Generating Station and the Four Corners Power Plant. They provide power to half a million homes and have been pinpointed by the Environmental Protection Agency as a major source of pollution––and a cause for reduced visibility in the Grand Canyon.

These two plants alone emit more than 28 million tons of carbon dioxide each year, triple the emissions from facilities in Washington state, fueling a vicious cycle of drought and worsening climate change. The two other power plants are on the Fort Mojave Reservation in Arizona and the Uintah and Ouray Indian Reservation in Utah.

Environmental groups have charged that the Navajo plants are responsible for premature deaths, hundreds of asthma attacks and hundreds of millions of dollars of annual health costs. The plants, which are owned by public utilities and the federal government, export a majority of the power out of the reservation to serve homes and businesses as far away as Las Vegas and help deliver Arizona’s share of the Colorado River water to Tucson and Phoenix. Meanwhile, a third of Navajo Nation residents remain without electricity in their homes.

Tribal leaders contend that power plants on Indian land deserve special consideration.

“The Navajo Nation is a uniquely disadvantaged people and their unique situation justified some accommodation,” Ben Shelly, president of the Navajo Nation, wrote in a letter to the EPA. He contends that the region’s underdeveloped economy, high unemployment rates and reliance on coal are the result of policies enacted by the federal government over several decades. If the coal plants decrease power production to meet emissions targets, Navajos will lose jobs and its government will receive less revenue, he said.

Many local groups, however, disagree.

“I don’t think we need special treatment,” said Colleen Cooley of the grassroots nonprofit Diné CARE. “We should be held to the same standards as the rest of the country.” (Diné means “the people” in Navajo, and CARE is an abbreviation for Citizens Against Ruining our Environment.)

Cooley’s Diné CARE and other grassroots groups say the Navajo leaders are not serving the best interest of the community. The Navajo lands have been mined for coal and uranium for decades, Cooley said, resulting in contamination of water sources and air pollution. She said it’s time to shift to new, less damaging power sources such as wind and solar.

The Obama administration’s carbon regulations for power plants aim to reduce emissions nationwide 32 percent by 2030 from 2005 levels. In its final version of the rule, the EPA set uniform standards for all fossil-fueled power plants in the country. A coal plant on tribal land is now expected to achieve the same emissions reductions as a coal plant in Kentucky or New York, a move that the EPA sees as more equitable. The result is that coal plants on tribal lands—and in coal heavy states such as Kentucky and West Virginia—are facing much more stringent targets than they expected.

The EPA has taken special efforts to ensure that the power plant rules don’t disproportionately affect minorities, including indigenous people. Because dirty power plants often exist in low-income communities, the EPA has laid out tools to assess how changes to the operation of the plants will affect emission levels in neighborhoods nearby. The EPA will also be assessing compliance plans to ensure the regulations do not increase air pollution in those communities.

The tribes do not have an ownership stake in any of the facilities, but they are allowed to coordinate a plan to reduce emissions while minimizing the impact on their economies. Tribes that want to submit a compliance plan must first apply for treatment as a state. If the EPA doesn’t approve, or the tribes decide not to submit a plan, the EPA will impose one.