By Eisa Ulen, Indian Country Today Media Network

Mainstream Americans continue to battle over the availability of Plan B. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) determined that the emergency contraception, sometimes known as the morning after pill, must be sold over the counter (OTC) to any woman age 15 and older who asks for it. A strong contingent of Americans, including activists, health care providers and at least one federal judge, have criticized the FDA, saying that Plan B should be available to any woman of any age who asks for it over the counter. The FDA has countered that younger women of child-bearing age cannot safely use Plan B without the assistance of a healthcare provider. As this public debate rages on, too few media outlets have reported on the barriers Native women of all ages have had trying to access Plan B. Until recently, even Native women well past their teen years have been unable to obtain Plan B as an OTC at Indian Health Service (IHS) Units throughout Indian country.

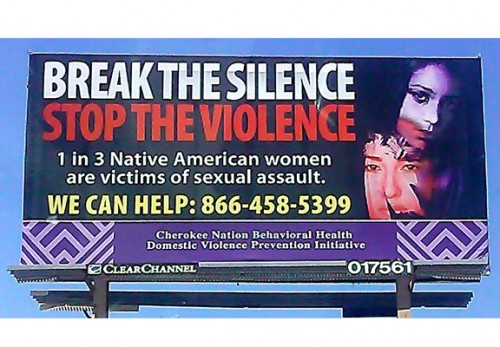

Plan B is the emergency contraceptive routinely given to women after rape has occurred. Because 1 in 3 Native women will be the victim of a sexual assault in her lifetime, the Native American Women’s Health Education Resource Center (NAWHERC) has worked to secure Native women’s legal right to Plan B, so that women on reservations can access this emergency contraceptive in the crucial first 24 hours after sexual contact has occurred, when the pill is most effective in preventing conception of the egg and sperm.

While the battle to make Plan B available over the counter to Native women at IHS units continues, progress has been made through the activism of NAWHERC. South Dakota-based Charon Asetoyer, CEO of the Native American Community Board, runs NAWHERC. In February of 2012, Asetoyer and Pamela Kingfisher published the NAWHERC Roundtable Report on the Accessibility of Plan B as an OTC within the Indian Health Service. This document exposed the inconsistencies between Native women’s legal right to Plan B, and the failure of IHS to provide this emergency contraception on demand and over the counter.

Indeed, given the fact that Native women experience rape at levels that are comparable to the rates of women living in war zones, NAWHERC identified the failure of IHS to make Plan B accessible over the counter as more than a legal issue. NAWHERC identified this failure to adequately protect Native women from conceiving a child following sexual assault as a human rights issue.

Much like the mainstream public debate regarding the availability of Plan B to younger American women, IHS has forced Native women of all ages to see a health care provider before they can access Plan B. Not only is this time- and cost-prohibitive for many women in Indian country, it too often demoralizes the woman seeking care. Asetoyer says she has heard of health care providers who, “in some cases, chastise a woman, blame her” for requesting a prescription for Plan B. No woman should have to answer questions about her use of birth control in order to access emergency contraception. As Asetoyer says, “that is extremely dehumanizing.”

Alexa Kolbi-Molinas, staff attorney for the American Civil Liberties Union Reproductive Freedom Project, says, “Certainly, the devastatingly high rate of sexual assault among Native women makes access to emergency contraception all the more critical, but even if that were not the case the inability of Native women to obtain emergency contraception at IHS facilities would be a violation of their basic civil and human rights: Every woman should have the opportunity to prevent an unplanned pregnancy and to decide whether and when is the right time, for her, to become pregnant. Moreover, the United States government is under a distinct legal obligation to ensure that Native women have access to comprehensive health care.”

While the Roundtable Report was published last year, Asetoyer says that as far back as 2005 her organization started “working and organizing women” around the subjugation of Native women who attempt to access Plan B. “IHS was extremely resistant” to the efforts of NAWHERC to liberate Native women from this dehumanization, Asetoyer says. “They just do not like standardization of any kind.”

Despite that resistance, standardization is coming. The 2009 omnibus bill mandated standardization of Sexual Assault Nurse Examiners (SANE nurses) within IHS. According to Asetoyer, $3 .5 million was allocated for the rigorous training required to be certified as a SANE nurse. These health care providers not only improve health outcomes for victims of sexual assault, they also aid law enforcement in prosecuting rapists. In addition, Asetoyer says the 2010 Tribal Law and Order Act signed by President Obama standardized sexual assault policies and protocols within IHS.

However, more needed to be done. IHS was still not making Plan B available over the counter. Asetoyer says she and her colleagues “realized we had to continue to work” on the availability of Plan B within IHS. NAWHERC contacted leaders in the community of reproductive justice advocacy and asked if they would upload the Roundtable Report and share it electronically with their followers on one day in March 2012 that would be called Push the Button Day. NAWHERC contacted the Boston Women’s Health Book Collective, the National Women’s Health Network, the National Black Women’s Health Project, the National Organization for Women, the Women of Color Network, and the Center for Reproductive Rights, among others. “They said yes,” Asetoyer says, and Push the Button Day was launched. Word about the realities of Native women “got out there, and it got out there fast, and it got out there not only in Indian Country but in the mainstream,” Asetoyer says. “People were shocked. They were appalled.”

In addition to disseminating information on Push the Button Day, Asetoyer and Kingfisher appeared with Dr. Susan V. Karol, chief medical officer for Indian Health Service, on the radio show Native America Calling. During the broadcast, Asetoyer says, Karol stated that emergency contraception was accessible at IHS units on-demand and “behind the counter.” (This term describes where the emergency contraception is physically placed and means women must ask the pharmacist for it.) But, as reported in ICTMN, Native women weren’t able to access Plan B without a prescription at all. “We really caught IHS not even knowing what was going on in their own service units out in the field.” (Read: Despite High Incidence of Rape, Women Denied Right to Plan B)

Asetoyer says that the story of Native women’s inability to access Plan B over the counter at IHS units started to appear in other media within 24 hours after the Native America Calling radio show aired.

As a follow-up with IHS, NAWHERC contacted Dr. Karol with a letter and asked her when emergency contraception would be available over the counter. Asetoyer says that, on May 21, 2012, her office received a response letter stating that IHS was finalizing policy to make Plan B available “behind the counter” and as an over the counter medication.

Frustrated that Native women could not access emergency contraception over the counter, while many college students in the mainstream were able to purchase it in an on-campus kiosk, Asetoyer began considering other options to pressure IHS. Asetoyer communicated with Senator Barbara Boxer of California and Senator Tim Johnson of South Dakota. Senator Johnson contacted IHS, Asetoyer claims, and received a letter from the Indian Health Service that was similar to her own. Senator Boxer, Asetoyer says, has been “working very diligently on access to emergency contraception.”

When Seantor Boxer’s office was contacted and asked to provide an interview for this article, Boxer spokesperson Peter True issued this statement: “Senator Boxer supports efforts to ensure that women, including women who rely on the Indian Health Service, can get access to the healthcare they need, including emergency contraception. She will continue to work towards that goal.”

In her last letter of communication with IHS, Asetoyer says she explained that NAWHERC would have to seek legal remedies if IHS refused to make Plan B available over the counter. In February of this year, the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) requested access to the policies IHS claimed it was working on to make EC available as an OTC.

Filed on behalf of NAWHERC under the Freedom of Information Act, this request spurred the IHS to action. “All of a sudden,” Asetoyer says, “IHS starts providing emergency contraception as an over the counter.”

“We decided, together with NAWHERC, to file the Freedom of Information Act because the government had been saying for too long that they were ‘working on’ a solution to this problem,” Kobi-Molinas says, “but no one was seeing any results. The purpose of the FOIA is to put an end to this stonewalling and force the government to explain what, if anything, it has been doing to ensure Native women could access EC OTC at IHS facilities.”

Asetoyer says her office has surveyed service units since the Freedom of Information Act was filed and has determined that over 40 IHS units, “almost all,” now provide emergency contraception to women who ask for it over the counter. This victory, Asetoyer says, is “based on a directive they received from area offices.” Asetoyer claims that, in response to the Freedom of Information Act, IHS Director Dr. Yvette Roubideaux was personally making telephone calls to IHS offices in order to make Plan B available over the counter.

When asked to provide an interview for this article, the IHS provided this official statement: “Emergency contraception is available in IHS federally-run facilities.”

Kobi-Molina explains: “A Freedom of Information Act request is essentially a tool for government accountability and transparency. This Freedom of Information Act does not directly make emergency contraception available, but it shines a spotlight on what the government is (or is not) doing to deal with this problem, and that sort of information is invaluable to advocates—democracy doesn’t happen behind closed doors, so a Freedom of Information Act makes sure those doors stay open.”

Despite the victories achieved in making emergency contraception available over the counter, Asetoyer says verbal directives can be rescinded, and NAWHERC wants a permanent solution put in place through written IHS policies. NAWHERC also wants 100 percent compliance at all IHS service providers.

To help more Native women understand their legal rights regarding Plan B, as well as its function in a woman’s body, NAWHERC is engaged in what Asetoyer calls “training in the community.” She adds, “we want to continue the process of demystifying emergency contraception.” NAWHERC has developed an Emergency Contraception Tool Kit to let Native people know that it is contraception, not an abortive, and so does not terminate a pre-existing pregnancy.

“The Tool Kit is a pack of information that will explain emergency contra: What it is. How it works. Your right to it,” Asetoyer explains. With a pamphlet, poster, fact-sheet, and PSAs for local radio stations, this Tool Kit will enable NAWHERC to launch the next phase of the struggle to make Plan B available – the public information phase. While the Tool Kit is aimed at school counselors, shelter advocates, those who work with victims of assault, and other professionals who work with women and girls, it is also intended for moms and other women to share at the kitchen table.

Asetoyer believes her office is charged with the task of informing Native women in part because the IHS suffers from paternalism and “old practices, old attitudes” that are hard to change. Citing past IHS protocols, like the sterilization of women without their consent, and inserting Norplant and refusing to remove it on demand, Asetoyer says the IHS still has “that old mindset: They know what’s best for us.”

Asetoyer notes that these are institutional issues and says that some providers within IHS have wanted to give EC OTC, but decision makers within IHS have had older ideas. Asetoyer adds that all those years of not providing EC OTC have communicated to Native women, and men, that “we don’t have the capabilities to make these kinds of intelligent decisions for ourselves.” Providing EC OTC, Asetoyer says, means acknowledging that “women know what’s best for their own bodies, their own reproductive health.”

NAWHERC is charging forward with two aims: to spread the word about the availability of EC OTC within IHS and to make this new situation within IHS permanent. In addition to informing women, Asetoyer says “we need to get this into policy. The struggle is not over.”

Read more at https://indiancountrytodaymedianetwork.com/2013/05/13/freedom-information-act-used-push-ihs-offer-plan-b-over-counter-149323