MSD adopts Since Time Immemorial curriculum during regular board meeting

By Brandi N. Montreuil, Tulalip News

MARYSVILLE – The work to correct history began long before the Marysville School Board met on December 8, to vote on adopting accurate tribal history and culture via the Since Time Immemorial curriculum into their district schools. The idea was first introduced by then newly elected Rep., John McCoy (D-Tulalip), in HB 1495 on January 26, 2005. The bill proposed requiring school districts to offer tribal history and culture along with Washington State and United States history curriculum. It passed 78-18 in the House on March 9, 2005. However, since then school districts have lagged in offering accurate tribal history on the 29 federally recognized tribes located in Washington state. On December 8, MSD decided to unanimously pass adopting the Since Time Immemorial curriculum as part of required curriculum in all their schools.

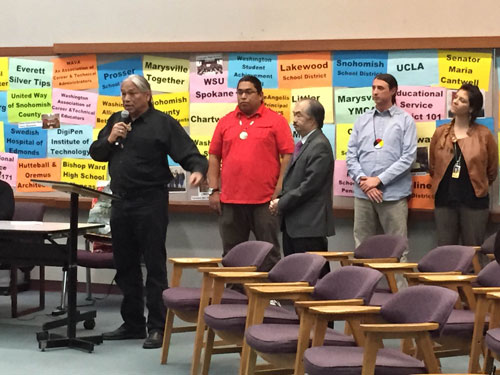

“This is awesome. This is a big district and to have a school board adopt it means a lot to us at the Native Office of Education, us as Indian people, and the people who created it. This is a great thing, because they are saying how important it is to start teaching about our history and our culture,” said Denny Hurtado, the outgoing Director of Washington Office of Native Education, following the vote.

STI is the result of partnership between the State of Washington Office of Superintendent of Public Instruction, private and public agencies and several of the 29 federal recognized tribes in Washington state. The curriculum provides a basic framework of Indian history and understanding of sovereignty for grades k-12. Aligned with the Common Core standards for English, language and art, STI lessons can be adapted by teachers to reflect the specific histories of tribes in their local area.

Teachers Shana Brown from the Seattle School District who is of Yakima dependency, Jerry Price, a middle school teacher with the Yelm School District and Elese Washines, an educator in the Yakima Nation Tribal schools, developed the curriculum under the leadership of Hurtado. STI was designed not just for non-Native students, but also for Native students. Its purpose, explained Hurtado to MSD board members, is to breakdown Native American stereotypes and misconceptions and to build bridges between tribal communities and non-Native communities.

“All they [students] know about us is what they learned in school, which is very little, and what you see on TV, which is not true, and what you read about during Columbus Day and Halloween,” Hurtado said before the vote. “I didn’t want this curriculum to seem like it was just an Indian thing. This was a true partnership to develop something good for our school to use. The purpose is to build bridges between our community and your community. That is a big point for us Indian people, because we have a lot of mistrust of the education system because our first experience of education was the military boarding schools.”

Over 1,000 teachers have received STI training by the Washington State Office of Native Education and 30 percent of school districts in Washington are using STI curriculum in some shape or form. Montana, Oregon and Alaska have also adopted STI curriculum in their school districts, and currently the Seattle School Board is looking into implementing it into their schools.

Matt Remle, a Lakota Native from the Standing Rock Reservation and Native American Liaison with MSD, who was present for the voting, said the change was long overdue. Fellow liaison, Eliza Davis, Tulalip tribal member, said the history of her own Tribe was lacking during her high school education.

“I graduated from Marysville-Pilchuck High School. I remember in Washington State history we watched the movie “Appaloosa.” That is what I remember of Washington State history. I don’t remember learning a whole lot about our Indian people or about Tulalip Tribes. I support the curriculum 100 percent. It is so important for our kids, all of our kids, and the whole community to understand the true history of all Washington Tribes, and also the history of Tulalip, Marysville, and what Tulalip does for this community as a whole. I think adopting this curriculum is the right direction.”

“I am excited for this day. I am excited about this and I am ready to approve this. We should have had this a long time ago,” said MSD board member Chris Nation right before the unanimous vote.

For more information on STI, please visit the website www.indian-ed.org.

Brandi N. Montreuil: 360-913-5402; bmontreuil@tulalipnews.com