By Micheal Rios, Tulalip News

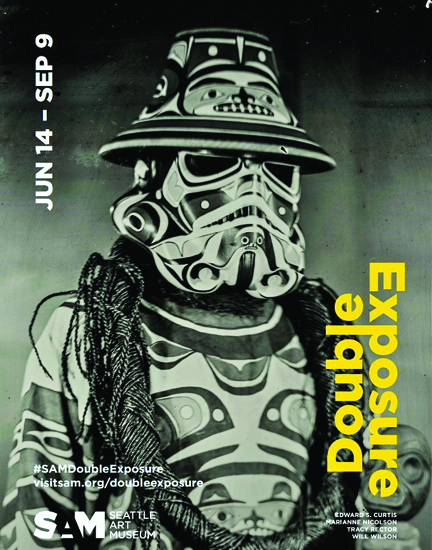

The Seattle Art Museum (SAM) presents Double Exposure: Edward S. Curtis, Marianne Nicolson, Tracy Rector, Will Wilson (on display from June 14 – September 9). Featuring iconic early 20th-century photographs by photographer Edward S. Curtis alongside contemporary works – including photography, video, and installations – by Indigenous artists Marianne Nicolson, Tracy Rector, and Will Wilson. Their powerful portrayals of Native identity offer a compelling counter narrative to the stereotypes present in Curtis’s images.

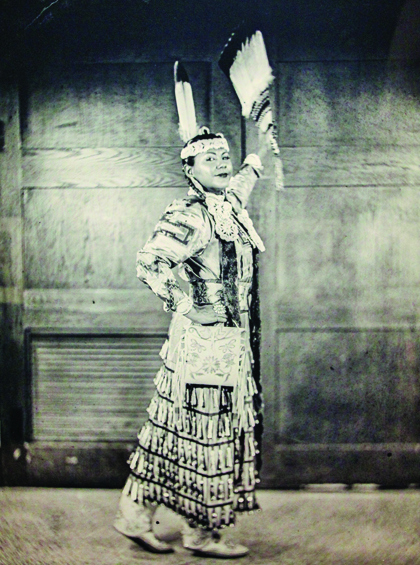

Edward S. Curtis is one of the most well-known photographers of Native people and the American West. Double Exposure features over 150 of his photographs. Threaded throughout the galleries of his works are multimedia installations by Marianne Nicolson, Tracy Rector, and Will Wilson. Their work provides a crucial framework for a critical reassessment and understanding of Curtis’s representations of Native peoples, while shedding light on the complex responses Natives and others have to those representations today.*

“The historical significance of Curtis’s project is well-established,” says Barbara Brotherton, SAM’s Curator of Native American Art. “In many cases, his photographs and texts provide important records of Native culture. However, it’s time for a reevaluation of his work. His methodology perpetuated the problematic myth of Native people as a ‘vanishing race.’ This exhibition reflects a collaboration among SAM, the artists, and an advisory committee comprising Native leaders to make a space for a reckoning with Curtis’s legacy.”

“The historical significance of Curtis’s project is well-established,” says Barbara Brotherton, SAM’s Curator of Native American Art. “In many cases, his photographs and texts provide important records of Native culture. However, it’s time for a reevaluation of his work. His methodology perpetuated the problematic myth of Native people as a ‘vanishing race.’ This exhibition reflects a collaboration among SAM, the artists, and an advisory committee comprising Native leaders to make a space for a reckoning with Curtis’s legacy.”

Three contemporary Indigenous artists in Double Exposure challenge assumptions about Native art and illustrate how Native communities continue to creatively define their identity and cultures for themselves. First Nation artist Marianne Nicolson created an immersive sculptural light installation that casts moving shadows to address the impact of the 1964 Columbia River Treaty on Native communities.

Seminole and Choctaw filmmaker/artists Tracy Rector empowers Indigenous communities by capturing the activism, defiance, and reclaimed traditions of Native tribes through her new video work of short stories derived from environmental awareness and life experiences of Natives today.

“All of my work is centered in Indigenous story: for, by, and about Indigenous people,” says Rector, whose video will welcome viewers inside a “Native-activated space” surrounded by related art.

Will Wilson’s large-scale tintype portraits feature Native lawmakers, artists, educators, and community members from the Seattle area. Artist Tracy Rector, Senator John McCoy, and others will speak through “talking” tintypes created using augmented reality. Wilson, a Navajo/Diné photographer, aims to counter stereotypes that Curtis’s work propagated.

“I want to supplant Curtis’s ‘settler’ gaze and the remarkable body of ethnographic material he compiled with a contemporary vision of Native North America,” states Wilson.

Double Exposure is a chance to see art of Native Americans in all its complexity through each of these artists’ perspectives on culture and identity.*

In honor of Double Exposure’s opening, the Seattle Art Museum invited any individuals with tribal affiliations to be the first visitors to view the exhibit. Dubbed ‘the Indigenous Peoples opening’, held the evening of June 11, representatives from many Coast Salish tribes gathered at SAM for the free event which included admission to the exhibit, performances by the Suquamish canoe family, and songs shared by Lummi violinist Swil Kanim.

“This Indigenous-only celebration was inspired by Miranda Belarde-Lewis (Tlingit/Zuni),” explains artist Tracy Rector. “She suggested the idea of decolonizing curation and what it means to indigenize museum spaces. Having a Native-centered exhibit opening is a way we could be in community experiencing artwork together.”

*source: Seattle Art Museum press releases, exhibition literature

Image credits: Kalamath Lake Marshes, 1923, Edward S. Curtis, goldstone. Mussel Gatherer, 1900, Edward S. Curtis, photogravure. John McCoy (Tulalip) – Talking Tintype, 2018, Will Wilson, exhibition print. Madrienne Salgado (Muckleshoot) – Talking Tintype, 2018, Will Wilson, exhibition print.