Officially, Memorial Day is a day on which war dead are honored. Unofficially, it’s a universal day of remembrance for all who have passed on. Many Americans will visit cemeteries over this holiday weekend in order to offer prayers, respect and honor to the graves of warriors and non-warriors alike.

Americans take great care in honoring their dead with fine monuments marking their lives and impact they have made on the world. To express anything other than respect for these sites would be considered downright un-American. The ancestors of Native peoples, however, are frequently not afforded this most basic level of humanity. Our dead often rest in mounds or sites that are marked with far more subtle methods than stone markers.

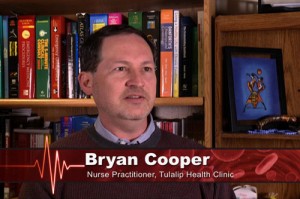

“There are cemeteries in Europe that are as old as our Native burial mounds here in the U.S. The only difference is that they have headstones with last names that can still be found in the immediate community,” said Kim Wesler, former director of the Wickliffe Mounds site in Kentucky.

The Ohio River Water Walk is the third Nibi walk lead by a group of Anishinabe grandmothers who pray for the water and raise awareness about the pollution that plagues this element that is essential to life. They began the walk in Pittsburgh on April 22, Earth Day, and are concluding their journey on Memorial Day near Wickliffe Mounds, a gesture that sends a poignant, potent message in both time and place.

RELATED: How Strong Ojibwe Women Made Mother’s Day Special by Fighting for the Waters

Once a notorious example of racial disregard for Native burial sites, Wickliffe Mounds now stands as a tribute to what can be accomplished by tribal and mainstream collaboration in reclaiming the sacred.

The Nibi Walkers traveled 981 miles from the source to the mouth of the Ohio River, the most polluted river in America in efforts to reconnect people with the sacred element essential to life. Completing the journey at Wickliffe Mounds has an added bonus of underscoring the treasured graves of Native ancestors that have too often been disrespected and desecrated by mainstream America.

On this Memorial Day in Kentucky, commemorations will include ceremony not only for the war dead of the U.S., but for the many warrior and non-warrior Native ancestors, perhaps killed in defense of their homelands.

Sharon Day, Ojibwe, leader of the walk noted that the Ohio River valley is home to many sacred sites and burial mounds. “It is sad to see such a sacred area treated so badly by pollution and disregard for the ancestors who lie here,” she said.

Looting of Native graves by amateur and professional collectors in search of artifacts was not an uncommon practice in this region. According to historians with the Ancient Trail of Ohio, hundreds of mounds in Ohio alone have also been destroyed by farming and development.

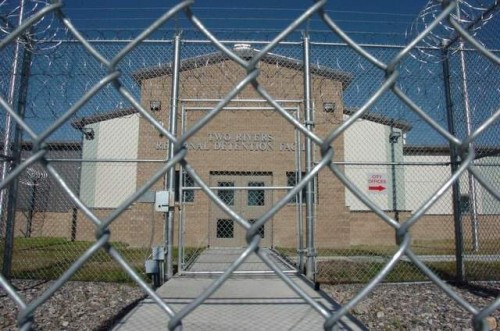

For generations, Wickliffe Mounds exemplified disrespect for Native sacred places and burial sites.

The modern story of Wickliffe Mounds began in 1932 when Fain King, the owner of the site opened a number of burial mounds on his property, unearthing the bones of hundreds of men, women and children from the Mississippian culture. According to the Kentucky Parks Service, they were likely buried around 1200 A.D. in the large settlement located on a bluff overlooking the confluence of the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers. King created a roadside tourist attraction from his find. He dubbed it “The Ancient Buried City,” where he offered paying customers a close up view of the remains. After removing the tops of the mounds, he built walkways over the graves where ancestors lay interred with pottery and other items. One of the opened mounds offered for public view contained the remains of many infants. The operation continued until 1983 when it was given to the Murray State University of Kentucky. Murray State operated the site until 2004 when Kentucky State Parks took over, making Wickliffe Mounds the 11th Kentucky state historical site.

Wesler, archaeologist and current director of the Remote Sensing Center at Murray State, was charged by the university with taking over the site in 1983. Although he had little knowledge at the time of the cultural concerns of Native peoples regarding treatment of remains, he knew immediately that the bones needed to be taken off display. “I got a crash course in Native American cultural awareness,” he recalled.

“I soon learned that when you define the past as family, you take it personally,” he remarked about those early conversations with tribal peoples whose ancestors are interred in the mounds.

The road to reburial was not easy in those early days for a traditionally trained archaeologist like Wesler. “The archaeological establishment was strictly anti-reburial in those days,” he recalls. One of his colleagues threatened to sue him if he went through with reburial efforts. He was threatened with legal action from a tribe upset about not being involved in consultations. Many community members also expressed anger over the reburial efforts and the decision to remove remains from public display. “The bones were on display for over 60 years. People grew up seeing them and wanted their children to see them. It was sort of a tradition here,” he said.

As he worked to make contacts and build relationships with the Native community, Wesler took the bones off display and replaced them with plastic replicas. The plastic bones served as placeholders, he said, as he struggled to strike a compromise among stakeholders.

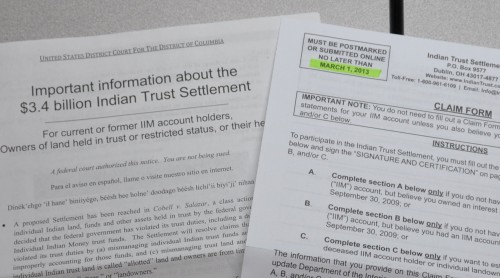

The plastic replicas and walkways over the gravesites remained until 2011 when the Chickasaw Nation assisted in reburying the remains. The Oklahoma Intertribal Council of the Five Civilized Tribes determined that since the Chickasaw were the closest living descendants of the Wickliffe ancestors they should lead reburial efforts.

RELATED: Honoring Ceremony Held for Reburied Ancestral Remains at Wickliffe Mounds in Kentucky

During the 2012 ceremony celebrating the reburial of over 400 ancestors from the mounds, Jefferson Keel, Lt. Governor of the Chickasaw Nation noted in his speech that in the past, Wickliffe was a place of desecration. Certainly no Native person would have wanted to visit such a place. Carla Hildebrand, manager of the site that is now owned and operated by the Kentucky State Parks Service, recalled Keel’s words.

“He spoke positively about the growing cooperative relationship between tribes and mainstream officials that allowed the reburial to happen. He said, ‘Now we can move forward,’” she recalled.

The story of Wickliffe Mounds is profound according to Hildebrand. She reports that numbers of Native groups such as the Nibi Walkers now stop in to pay their respects. “I’m happy that the mounds are getting the respect and attention due them,” she said.

“I’m grateful I got to keep those promises made to Native people along the way,” Wesler said.

The history of Wickliffe Mounds reflects a slowly maturing societal opinion regarding Native burial sites, noted Wesler.

Hildebrand noted that in recent years many people expressed discomfort about having the plastic bone replicas on display. “People’s sensibilities are maturing, we are seeing a change in attitudes. People from differing backgrounds would tell us they thought even the plastic replicas were disrespectful,” she said.

Unfortunately, however, modern farming, graveling and urban sprawl continue to take a toll on sacred sites, according to the Ancient Trail of Ohio website. Following are three examples in a long list of ongoing battles between developers and preservationists over protecting sacred sites.

Wal-Mart has a history of destroying sacred sites. They have built or attempted to build stores on burial mounds in Missouri, Tennessee, Georgia, California, and Hawaii. In 2004, Wal-Mart opened a store in Mexico City within view of the 2000-year-old pyramids of Teotihuacan despite protests by local residents.

The owner of Wingra Redi-Mix in Wisconsin wants to destroy a bird effigy mound on his property in order to get at copy million worth of gravel buried beneath. The mound, part of the Ward Mounds, have been called the “Heart of the homelands of the Ho-Chunk Nation.” Effigy mounds in Wisconsin were built as long ago as 700 BC.

Recently preservationists narrowly succeeded in saving the most important surviving Adena earthworks in the Ohio Valley from developers.

Sharon Day is pondering the significance of finishing her 981-mile journey along the Ohio River near Wickliffe Mounds. Seeing the destruction of the water, earth and sacred sites along the way brings home a message from a long ago Shawnee leader, Tecumseh, who called on people to unite and take action to protect the earth.

“….soon the trees will be cut down to fence in the land. Soon their broad roads will pass over the graves of your fathers and, the place of their rest will be blotted out forever. The annihilation of our race is at hand unless we unite in common cause.”