By Steve Tetreault and Henry Brean, Las Vegas Review-Journal

WASHINGTON – Two bills introduced Tuesday in the U.S. Senate would grant more than 26,000 acres of federal land to the Moapa Band of Paiutes outside Las Vegas and expand reservations of seven Northern Nevada Indian tribes.

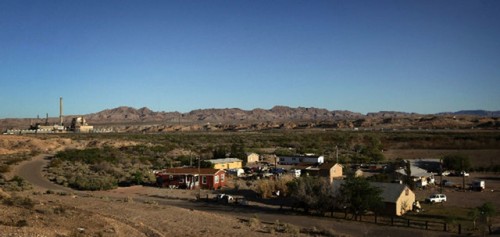

One of the bills by Sen. Harry Reid, D-Nev., would expand the 75,000-acre Paiute reservation by about a quarter by putting into trust 26,565 acres currently controlled by the Bureau of Land Management and Bureau of Reclamation. The Moapa tribe consists of 329 people, 200 of whom live on the reservation 30 miles north of Las Vegas.

The second bill would grant almost 93,000 acres to tribes in Humboldt, Elko and Washoe counties, and to the Pyramid Lake Paiutes, whose reservation includes land in Washoe, Storey and Lyon counties.

“Land is lifeblood to Native Americans, and this bill provides space for housing, economic development, traditional uses and cultural protection,” Reid said in a statement.“I take the many obligations that the United States has to tribal nations seriously.”

Reid has a long relationship with Nevada tribes, and has helped them settle land and water disputes over the years. He is also trying to pressure Washington Redskins owner Dan Snyder to changing the team name considered racist and offensive by many American Indians. On Monday, Reid rejected team president Bruce Allen’s invitation to attend a game this fall. Allen said he hoped the experience would persuade the Nevada senator the team name is an expression of “solidarity” with Native Americans.

ECONOMIC FACTORS

Moapa Paiute tribal chairwoman Aletha Tom said Tuesday the additional land “means a great deal.”

“It’s a good idea for our tribe, for our cultural preservation and economic development,” she said.

In recent years, the Moapa Band of Paiutes has pursued development of renewable energy on its land, moving to fulfill a Reid ambition to make Nevada a major player in solar and wind energy generation.

In May, federal officials cleared the way for a new 200-megawatt photo-voltaic array to be built on tribal land with the backing of NV Energy. The facility on 850 acres is expected to generate enough electricity for about 60,000 homes.

In March, the tribe broke ground on a 250-megawatt plant billed as the first utility-scale solar project approved on tribal land. The project could generate electricity to feed 93,000 homes by the end of 2015. The City of Los Angeles has agreed to buy power from the 1,000-acre array for 25 years under a deal worth about $1.6 billion.

Tom said the project is on land the tribe obtained in 1980, when the reservation was last expanded. If Reid’s legislation is successful, the tribe will pursue solar power development on its new land as well, she said.

In the 1870s, the Moapa Paiute reservation spread over two and a half million acres, including much of what today is Moapa Valley, Bunkerville, Logandale, Glendale, Overton and Gold Butte. But most of it was stripped away by Congress.

In 1980 President Jimmy Carter restored 75,000 acres, roughly 117 square miles.

In recent years, Reid has publicly sided with the tribe in its fight against NV Energy over an aging coal-burning power plant next to the reservation. Tribe members blame smoke and blowing dust from the Reid Gardner Generating Station for making them sick and polluting their land. In 2012, Reid described the plant as a “dirty relic” and called on NV Energy to close it.

The utility responded last year by announcing plans to shut down three of the four units at the 50-year-old power plant by the end of this year and shutter it completely in 2017.

Barbara Boyle of the Sierra Club helped the tribe fight the power plant. She said the reservation expansion should help both the tribe and the environment.

“After working with them on this fight, I believe that transferring more of their ancestral lands back to the Moapa Band is just, and will ensure that the land benefits the environment as well as the health of the people and their economy,” Boyle said in a statement from the national conservation group.

Rep. Steven Horsford, D-Nev., whose district includes the Moapa Paiute reservation, said he supports the expansion.

Sen. Dean Heller, R-Nev., is cosponsor of the bill benefiting Northern Nevada tribes, which he sees as a path to economic opportunity for them. But he is still studying the Moapa Paiute bill and seeking input from the tribe, according to spokeswoman Chandler Smith.

OTHER RESERVATION LAND

The second Reid bill introduced Tuesday:

— Conveys 373 acres of BLM land to be held in trust for the Elko band of the Te-Moak Tribe of the Western Shoshone Indians.

— Grants 19,094 acres of BLM land to be held in trust for the Fort McDermitt Paiute and Shoshone Tribe.

— Transfers 82 acres of Forest Service land to be held in trust for the Duck Valley Shoshone Paiute Tribes.

— Conveys 941 acres of BLM land to be held in trust for the Summit Lake Paiute Tribe.

— Gives 13,434 acres of BLM land to be held in trust for the Reno-Sparks Indian Colony.

— Conveys 30,669 acres of BLM land to be held in trust for the Pyramid Lake Paiute Tribe.

— Releases the Red Spring Wilderness Study Area and conveys 28,162 acres of BLM land, including the released land, for the South Fork Band Council.

The bill also includes 275 acres for the city of Elko for a motocross park.

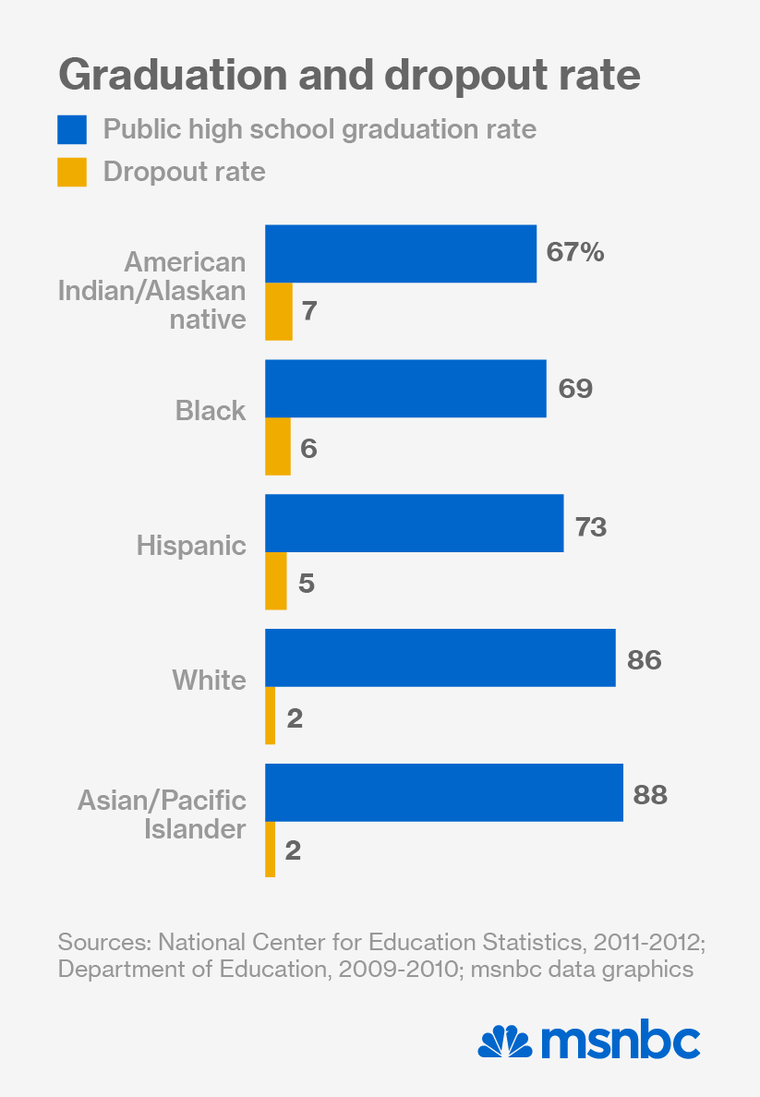

The BIE blames its failures on “an inconsistent commitment from political leadership,” institutional, budgetary and legal barriers as well as bureaucratic red tape among federal agencies. Those systemic issues have produced a disjointed system that has even clogged up the delivery of required materials, including textbooks.

The BIE blames its failures on “an inconsistent commitment from political leadership,” institutional, budgetary and legal barriers as well as bureaucratic red tape among federal agencies. Those systemic issues have produced a disjointed system that has even clogged up the delivery of required materials, including textbooks.