By Micheal Rios, Tulalip News

Tulalip Youth Services celebrated “Say Hello Week” with an added focus of taking the stigma out of mental health awareness. The week included a variety of learning activities for the children and teenagers of the community. The biggest event was without a doubt the open house and grand opening of the C.R.E.A.T.E. Space on Friday, February 2.

From 10:00am-6:30pm on that Friday, the 2nd floor of the Youth Center was a destination for celebration and hands-on learning while becoming acquainted with the newly created space designed for inclusion, offering a place for community youth to go when they need to decompress.

C.R.E.A.T.E. Space stands for Calm Room & Expressive Art to Empower. It’s the result of a collaborative effort of the Methamphetamine Suicide Prevention Initiative through Behavioral Health and Youth Services. All community members and youth are invited to visit the space and learn more about its uses and how to remove the stigma and shame surrounding mental health issues.

“With the recent creation of the Tulalip Special Needs Parent Association by several key community members and Youth Services, we wanted to honor the great work that’s going on by making sure that we create activities and places that are wholly inclusive of all youth,” explained Monica Holmes, C.R.E.A.T.E. Space designer and Parapro for the M.S.P.I. Grant. “That meant taking a look at our facilities first and asking the question: Are we accessible in every sense of the word to our youth with special needs be they social, emotional, physical or mental?

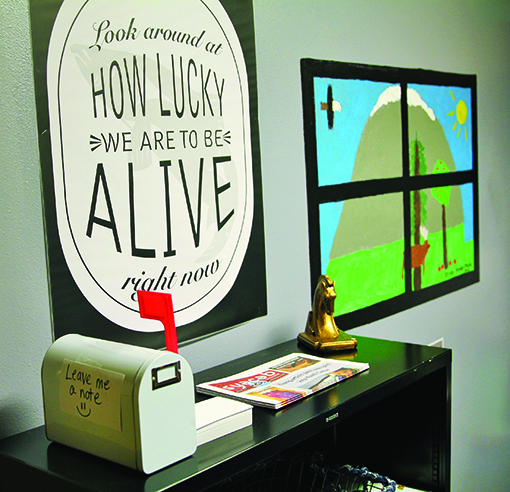

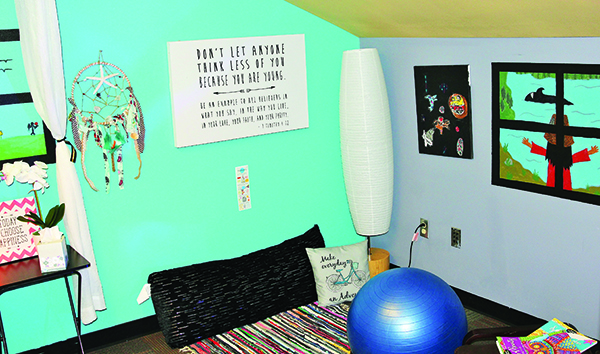

“The C.R.E.A.T.E. Space has two major components that were developed to meet those needs. The Calm Room is a sensory inclusive space with various elements that can be utilized to provide a sensory environment which promotes a sense of calm and well-being, while addressing the individual sensory input needs of our youth with sensory overload challenges. We’ve stocked it with items like play dough, Legos, fidgets, soft furnishings, lower lighting, colored mood lighting, essential oil infusers, nature sound machine, yoga mats and resistance bands that can deliver the right amount of sensory input and/or relax the nervous system that is agitated or overloaded by typical lights and sounds of most spaces.

“The Expressive Art studio is the second component to the C.R.E.A.T.E. Space which serves youth in a unique fashion. It doubles as an art studio and gathering spot for teens who want to hang out in a homey, quiet, comfortable location to interact in small groups or one-on-one with a staff member trained to use art and games as a means to express creativity and emotion in a safe space.”

For the grand opening event many Tulalip service departments were invited to setup their own information booths where they could interact with visitors to the Space. Community Health, Smoking Cessation, Problem Gambling, Chemical Dependency, and Behavioral Health were among those who accepted the invite. Partnerships are key in spreading awareness and resources to our community members. With all those services under one roof at the same time, they were able to let people know they have many choices and places to go for help with various addictions or issues. They also helped de-stigmatize the act of reaching out for help.

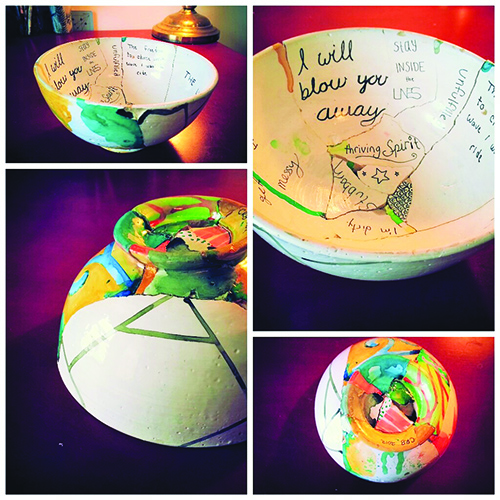

A variety of free expressive art classes were offered to visitors and attendees of the grand opening event. The one receiving the most youth attention and excitement was the Broken Bowl Project. The bowl represents us as an individual, we are vessels that hold many things. But sometimes we break and need to be put back together. Our brokenness changes us, makes us who we are. And so the painting on the outside of the bowl represents who we are on the outside, and the words on the inside of the bowl express all the hidden components that make us who we are.

“The lesson of the Broken Bowl Project is to embrace the brokenness, to add words and colors and fill the cracks and holes with beautiful reminders and positive messages about the things we have overcome or hope to be someday,” says Monica, who guided over fifteen youth undergoing the project. “But mostly we should be able to stand back and admire this new vessel we have become, not despite but inspite of all we have done, been or had happen to us.”

The C.R.E.A.T.E. Space is a place to decompress and also learn positive coping skills with an adult who has been trained to provide sensory appropriate options during times of high stress and overload. As the mother of four special needs children with sensory processing issues, Parapro Monica Holmes has spent years learning ideas from occupational therapists and creating spaces like this at her own home and in public settings for children.

Hours of C.R.E.A.T.E. Space are Monday – Friday from 3:30p.m. – 6:00p.m. Individual sessions can be made by appointment or small groups wanting a private setting can make a reservation. For more information please contact Monica Holmes at 360-631-3406 or mholmes@tulaliptribe-nsn.gov