Source: Northwest Indian Fisheries Commission

The Stillaguamish and Tulalip tribes have partnered with the state Department of Natural Resources and three private timber companies to map forestlands in the Stillaguamish and Skykomish basins.

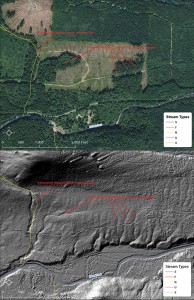

LIDAR, which stands for Light Distance and Ranging, uses an airborne laser to survey topography.

“The laser pulses from the plane are reflected back to record billions of points of light that measure elevation,” said Derek Marks, Timber/Fish/Wildlife biologist for Tulalip.

Elevation data was collected on working forestlands and a large area of Mount Baker-Snoqualmie National Forest. The result is a high-resolution model that enables natural resources managers to identify resources and potential risks, such as landslides.

“We can save many hours with high-resolution models,” Marks said. “We don’t have to walk the hillside; a forester would have to traverse the area to know where the streams are.”

The new LIDAR surveys covered an area that previously had not been mapped, where the forest canopy covers streams. The models will guide environmental permit reviews for logging and road proposals.

“We’re also reflying the entire North Fork Stillaguamish corridor to compare the data with LIDAR from 2003, to see what’s changed in a 10-year period,” said Scott Rockwell, Timber/Fish/Wildlife biologist for Stillaguamish. Those surveys will cover tribal restoration projects on the North Fork.

“It streamlines management and risk assessment for private industry and state lands,” Rockwell said. “It allows tribes to prioritize and scope restoration projects where we can see obvious habitat potential.”

The surveys were coordinated by the Puget Sound LIDAR Consortium, an informal group of federal and local agencies that acts as a clearinghouse for the high-resolution topographic models, making the data available to the public.