Peninsula Daily News and The Associated Press

Peninsula Daily News and The Associated Press

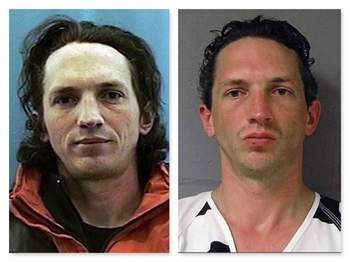

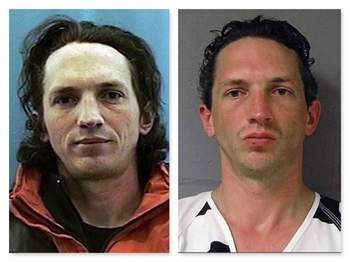

PORT ANGELES — FBI agents have linked 11 killings to admitted serial killer Israel Keyes, including five murders from 2001 to 2006 while he lived in Neah Bay.

Keyes told agents he weighed down at least one body with anchors and dumped it from a boat into 100 feet of water in Lake Crescent, 18 miles west of Port Angeles.

The FBI on Monday released a timeline of travels and crimes by Keyes, a handyman and owner of an Alaska construction company who committed suicide in his Anchorage, Alaska, jail cell in December 2012 while awaiting trial for the kidnapping and murder of an 18-year-old barista.

Before his death, police said he admitted to at least seven other slayings, from Vermont to Washington state, hunting down victims in remote locations such as parks, campgrounds or hiking trails.

In a statement issued Monday afternoon, the FBI office in Anchorage said agents now have added three more to that grim tally, based on his statements, and said the timeline sheds some new light on a mysterious case that left a trail of unsolved killings around the country.

FBI spokesman Eric Gonzalez said the goal of releasing the information is to seek input from the public, to identify victims who remain unknown and to provide some closure to their families.

“We’ve exhausted all our investigative leads,” Gonzalez said.

Anyone who might have information about Keyes or possible victims is asked to call the FBI at 800-CALL-FBI (800-225-5324).

The FBI said Keyes lived in Neah Bay in 2001 after he was discharged from the Army.

While he was living there, Keyes committed his first homicide, according to the timeline.

The victim’s identity is not known, and neither is the location of the murder. Without giving any specifics, Gonzalez said the FBI did not know whether this murder occurred in Washington state.

The FBI documents said Keyes frequented prostitutes during his travels and killed an unidentified couple in Washington state sometime between July 2001 and 2005.

Keyes also told investigators he committed two separate murders between 2005 and 2006, disposing of at least one of the bodies from a boat in 12-mile-long Lake Crescent.

“Keyes stated at least one of the bodies was disposed of in Crescent Lake in Washington, and he used anchors to submerge the body,” the FBI said.

“Keyes reported the body was submerged in more than 100 feet of water.”

Keyes reportedly lived and worked in Neah Bay from 2001 to 2007, employed by the Makah tribe there for repair work and construction, before moving to Alaska.

When he killed himself in jail, the 34-year-old Keyes was awaiting a federal trial in the rape and strangulation murder of 18-year-old Samantha Koenig, who was abducted February 2012 from the Anchorage coffee stand where she worked.

Keyes confessed to killing Koenig and at least seven others around the country, including Bill and Lorraine Currier of Essex, Vt., in 2011.

Keyes also told investigators in Alaska that he killed four people in Washington, but names and details were lacking, according to an FBI news release.

He said he killed two people in separate incidents sometime in 2005 or 2006, and then “murdered a couple” in the state between 2001 and 2005.

The FBI said Monday that Keyes is believed to actually have killed 11 people, all strangers.

Keyes told investigators his victims were male and female, and that the murders occurred in fewer than 10 states, but he did not reveal all locations.

Koenig and the Curriers were the only victims named by Keyes because he knew authorities had tied him to their deaths.

Keyes told investigators only one other victim’s body besides Koenig’s was ever recovered, but that victim’s death was ruled as accidental.

The bodies of the Curriers were never found.

The FBI said Keyes admitted frequenting prostitutes, but it’s unknown whether Keyes met any of his victims this way.

Keyes said he robbed several banks to fund his travels along with money he made as a general contractor, and investigators have corroborated his role in two holdups, according to the FBI.

Keyes also told authorities he broke into as many as 30 homes throughout the country, and he talked about covering up a homicide through arson.

The timeline begins in summer of 1997 or 1998, when Keyes abducted a teenage girl while she and friends were tubing on the Deschutes River, he told investigators.

The FBI said Keyes was living in Maupin, Ore., at the time, and the abduction is believed to have occurred near that area.

Keyes moved to Anchorage in 2007 but continued to travel extensively outside the state.

After killing Koenig, Keyes flew to New Orleans, where he went on a cruise.

He left Koenig’s body in a shed outside his Anchorage home for two weeks, according to the FBI.

After the cruise, Keyes drove to Texas.

The FBI said that during this time, Keyes may have been responsible for a homicide in Texas or a nearby state — a crime Keyes denied.

Keyes was arrested in Lufkin, Texas, about six weeks after Koenig’s disappearance. He had sought a ransom and used Koenig’s debit card.

Three weeks after the arrest, Koenig’s dismembered body was found in a frozen lake north of Anchorage.

The FBI said Keyes also traveled internationally, but it’s unknown if he killed anyone outside the U.S.

He is known to have been in Belize, Canada and Mexico.

Remote areas

Keyes frequented remote areas such as campgrounds, trailheads and cemeteries to pick victims, according to the FBI.

While the specifics of his murders are largely unknown, the FBI hopes that by elaborating on Keyes’ whereabouts and the nature of his crimes, anyone with information might come forward to provide details on who Keyes’ victims may have been.

“In a series of interviews with law enforcement, Keyes described significant planning and preparation for his murders, reflecting a meticulous and organized approach to his crimes,” the FBI wrote in a release accompanying the timeline.

“It’s a more comprehensive timeline,” Gonzalez said of the updated breakdown of Keyes’ whereabouts.

“It’s based on investigations and on speaking with Keyes. It’s the best timeline that we have. We’re really just opening it up and putting it all out there at this point.”

Keyes killed himself by slitting one of his wrists and strangling himself with bedding, police said. He left behind an extensive four-page note that expressed no remorse nor offered any clues to other slayings.

He studied other serial killers but “was very careful to say he had not patterned himself after any other serial killer,” Anchorage Police Detective Monique Doll said last December.

Investigators said he had “a meticulous and organized approach to his crimes,” stashing weapons, cash and items used to dispose of bodies in several locations to prepare for future crimes.

Authorities have dug up two of those caches — one in Eagle River, Alaska, outside Anchorage, and one near a reservoir in the Adirondack Mountains of New York.