by Micheal Rios, Tulalip News

During the weeks of July 17-28, the Greg Williams court was home to the 20th Annual Lushootseed Day Camp. The camp was open to children age five to twelve who wanted to learn about their culture and Lushootseed language through art, songs, games, weaving and storytelling. Each year the Lushootseed Department teams up with the Cultural Resources Department, along with a select number of vital community volunteers, to hold two one-week camps. Each camp has openings for up to 50 participants, but, just as with years past, the camp’s first week total of 37 kids was easily eclipsed by the 70+ kids who attended the second week.

A new format brought a renewed sense of excitement and vigor to both the teachers and youth who participated. In previous years, all youth performed in one large play, which marks the end of camp. This year, the youth were divvied up into five smaller groups. Each group were taught a unique, traditional Lushootseed short story, and then performed that story in the form of a play at the camp’s closing ceremony. The stories taught were Lady Louse, Bear and Ant, Coyote and Rock, Mink and Tetyika, and Nobility at Utsaladdy.

Throughout the duration of camp, the children participated in eight different daily activities. The following list is what each group accomplished throughout the week:

photo/Micheal Rios

Art – painting, making candle holders and storybook drawings.

Games – played various outside games to bolster team building.

Songs – learned and practiced songs both traditional and created.

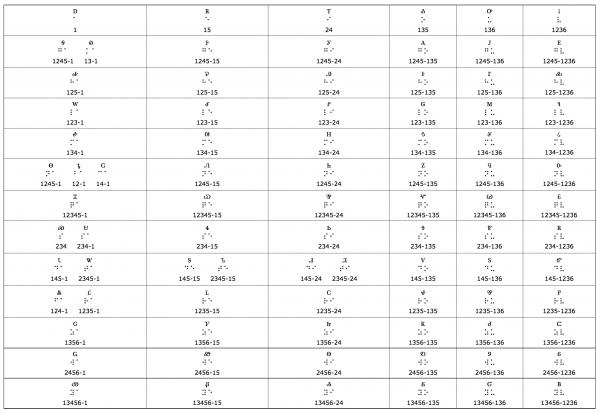

Language – learned key Lushootseed words that were in their play, various Lushootseed phrases and Lushootseed word games.

Play – learned, practiced and performed the plays Lady Louse, Bear and Ant, Coyote and Rock, Mink and Tetyika, and Nobility at Utsaladdy.

Technology – children learned and practiced Lushootseed materials related to the play using the Nintendo DSi handheld games created by Dave Sienko.

Traditional Teachings – learned various traditional stores and values.

Weaving – paper weaving, story mats, friendship bracelets, bookmarks and hand sewing.

“This year’s camp was dedicated to Edward ‘Hagen’ Sam for the songs, stories and teachings he has passed down,” explained Lushootseed language teacher and co-coordinator of the camp, Natosha Gobin, during the camp’s closing ceremony. “Through the recordings of stories and songs, Hagen continues to pass on many teachings that our department utilizes on a daily basis. Also, we give special acknowledgement to his son, William ‘Sonny’ Sam, for the gifts he gave to our department on behalf of his father.

Photo/Micheal Rios

Photo/Micheal Rios

“We would also like to honor Auntie Joy and Shelly Lacy for the vital work they did in the early years of Language Camp that have allowed us to continue hosting it as we celebrate the 20th year! They laid the foundation for camp and we raise our hands to them in gratitude for all they have done and continue to do for our youth and community.”

While the plays and closing ceremony for week one’s camp was held in the Greg Williams court, due to a loss in the community week two’s camp held their closing ceremony in the Kenny Moses Building. Regardless of the venue, both week one and two’s young play-performers made their debut to large community attendance, as family and friends came out in droves to show their support.

“We are so thankful to all the teachers, all the staff, and all the parents who volunteered to be a part of Language Camp and help our young ones learn our language. Our language is so important to us. It makes my heart happy that my children get to be here, that our children get to be here, to hear the words of our ancestors and to speak the words of our ancestors,” said ceremonial witness and former Board of Director, Deborah Parker. “Our kids continue to honor our ancestors by learning their songs and stories, then to perform them for us. I just hope and pray we continue to speak the words of our ancestors, to speak our Lushootseed language.”

When the plays had concluded and the ceremonial witnesses had shared a few words, there was a giveaway. The camp participants gave handmade crafts to their audience members, which preceded a light lunch of fried chicken, macaroni salad, baked beans and cupcakes.

Reflecting on this year’s 20th Annual Language Camp, Natosha Gobin beamed with pride, “No matter what goes on behind the scenes in planning and preparing for camp, it is always a success! We had over 100 youth attend camp and they all enjoyed each activity they participated in. I am extremely proud of my co-workers for their hard work and dedication to their activities. I believe that every year camp is offered, we continue to leave a lasting impression on our young participants, just as they do for us.”

For any questions, comments or to request Lushootseed language materials to use in the home, please contact the Lushootseed Department at 360-716-4499 or visit www.TulalipLushootseed.com

Photo/Micheal Rios

Photo/Micheal Rios

Contact Micheal Rios, mrios@tulaliptribes-nsn.gov