Native people are the most loving people in the world. And it makes sense—so many of us have seen this movie before.

We got our own problems, right? Still, ever since the Michael Brown tragedy in Ferguson, Missouri, I’ve received hundreds of Facebook messages and emails—Native people understanding the connection between black folks’ interaction with law enforcement and Native folks’ interaction with law enforcement. The Natives who’ve contacted me seem to know, “We’re not saying all police officers are bad. Heck, most are ok.” But those Natives know that when things do go haywire and a police officer does do something bad to someone, it’s usually someone brown. And when that brown-skinned person is killed or hurt badly, it’s usually for something small. Insignificant. Something that doesn’t deserve deadly force. Like allegedly stealing cigars.

That’s rough. But to quote Bill Murrary in Stripes, “That’s the fact, Jack!”

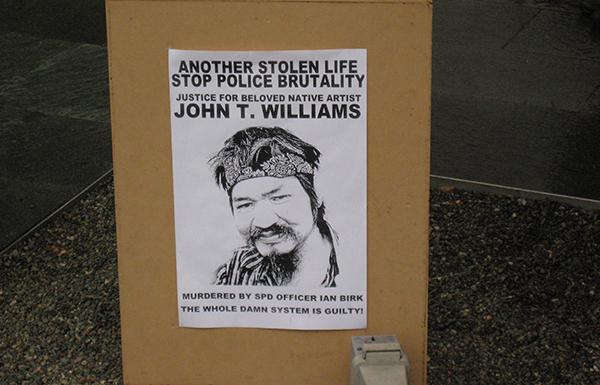

RELATED: The Shooting Death of John T. Williams

Those Natives told me—if I get a chance to write about this—to express that they understand the family’s profound sense of loss and grief. They were very clear when telling me that they stand with the people of Ferguson. They recognize this—this looks familiar. Maybe that’s why so many Native people are standing with the frustrated and grieving folks of Ferguson. Maybe that’s why so many are up in arms about this recent unnecessary death of yet another brown person.

Many of Natives have seen this movie before. This looks a lot like John T. Williams—the beautiful and brilliant Native carver, shot while breaking no laws by Seattle Police Officer Ian Burke. We recognize how the inquest tried to paint John T. as aggressive, as drunk—the same way that the Ferguson Police Department “leaked” information that Michael Brown may have had weed in his system.

So what? Who doesn’t have weed in their system?? Weed doesn’t make you aggressive—it makes you hungry and lazy. But the police department is attempting to make Brown look like a “thug”—which we all know is code for “ni**er.” We recognize this doublespeak, the smokescreen.

But I digress.

This movie looks a lot like the recent Becky Sotherland incident, tasing over and over and over an unconscious Native man in Pine Ridge. Or AJ Longsolider, 18 years old and died in a jail cell, sick yet no one from the state would help him.

This looks like Black Wall Street—there are plenty of Natives in Tulsa; we remember how Blacks caught hell for doing well. This looks like Oscar Grant—brutal. Unnecessary. Tragic.

Look, there are plenty of good police officers. I mean, I come from a “Don’t talk to the cops” family, but I also know that there are many who do their jobs every day respectfully and lovingly. This is not a condemnation of law enforcement—not at all. But it IS an observation about some law enforcement. I KNOW there are amazing police officers who engage in good and healthy practices—heck, just the other day, a member of the Suquamish Tribal Police took time out of his day to give instruction to my nephew that literally might save his life. That’s community policing. That’s beautiful. That’s the opposite of police brutality.

But when police brutality happens in this country, it happens to black and brown-skinned people entirely too much. Now I’m not saying I want it to happen to white people more—all I’m saying is that there are a WHOLE bunch of white folks who were convicted of ugly, violent crimes, and they were around and healthy to stand trial. And then there are a WHOLE bunch of black and brown people who weren’t alleged to have committed any crimes, or at worst a misdemeanor (like that pack of cigars), and those black and brown people aren’t alive anymore.

Seems inconsistent.

RIP John T. Williams. RIP Michael Brown. God bless all the victims of police brutality, of all colors.

Gyasi Ross

Blackfeet Nation/Suquamish Territories

Dad/Author/Attorney

www.cutbankcreekpress.com

Twitter: @BigIndianGyasi

Read more at http://indiancountrytodaymedianetwork.com/2014/08/22/police-brutality-against-black-and-brown-people-were-together-156533