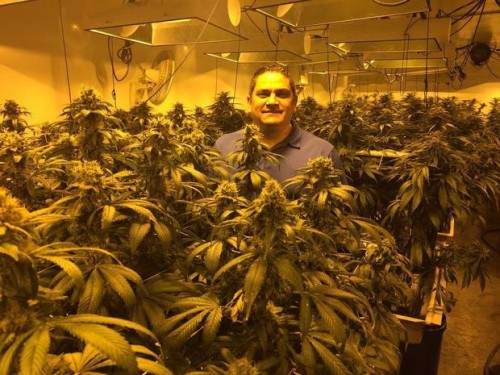

PHOTO COURTESY OF TONY REIDER — Handout

BY ROB HOTAKAINEN, Sun Herald

WASHINGTON — Tourists soon may be able to go to a South Dakota Indian reservation, buy a cigarette-sized marijuana joint for $10 to $15 and try their luck at the nearby casino.

In December, the Flandreau Santee Siouxexpect to become the first tribe in the nation to grow and sell pot for recreational use, cashing in on the Obama administration’s offer to let all 566 federally recognized tribes enter the marijuana industry.

“The fact that we are first doesn’t scare us,” said tribal president Anthony “Tony” Reider, 38, who’s led the tribe for nearly five years. “The Department of Justice gave us the go-ahead, similar to what they did with the states, so we’re comfortable going with it.”

The tribe plans to sell 60 strains of marijuana. Reider is hoping for a flock of visitors, predicting that sales could bring in as much as $2 million per month.

“Obviously, when you launch a business, you’re hoping to sell all the product and have a shortage, like Colorado did when they first opened,” he said.

Other tribes have been much more hesitant.

“Look at Washington state, where marijuana’s completely legal as a matter of state law everywhere, and you still have tribes adhering to their prohibition policies,” said Robert Odawi Porter, former president of the Seneca Nation of New York.

It comes as no surprise to Washington state Democratic Rep. Denny Heck, who says he works on tribal issues every day.

“Not once has anybody ever brought up that they wanted to go down this track,” he said.

Heck speculated on one possible reason: “We’re all aware of the painful history of alcoholism in Indian Country.”

Tribes won the approval to sell pot in December, when the Justice Department said it would advise U.S. attorneys not to prosecute if tribes do a good job policing themselves and make sure that marijuana doesn’t leave tribal lands.

But federal prosecutors maintain the discretion to intervene, a worrisome prospect for many.

“This administration is very pro-tribes, very supportive. What if the next one isn’t?” asked W. Ron Allen, chairman of the Jamestown S’Klallam Tribe in Washington state.

He said many of the state’s 29 tribes also want assurances from federal officials that they won’t lose millions of dollars in grants and contracts if they sell a drug banned by Congress.

“We’re not getting definitive answers back,” Allen said. “There’s a number of tribes that are very aggressively looking into it and trying to sort through all the legal issues. The rest of us are just kind of on the sidelines watching.”

Many tribal officials took note earlier this month when federal authorities seized 12,000 marijuana plants and more than 100 pounds of processed marijuana on tribal land in Modoc County, Calif.

Federal authorities said they raided the operation because the tribes planned to sell the pot on non-reservation land.

“That’s a warning shot to Indian County that this isn’t carte blanche to do whatever you want, even in a place like California,” said Blake Trueblood, director of business development for the National Center for American Indian Enterprise Development, based in Arizona.

Trueblood said marijuana could give tribes an economic boost, much like gaming. He said tribes will have the best opportunities in states such as Florida and New York, where demand for pot is high but the drug has not been legalized for recreational use by state voters.

“Ultimately, I think you’ll see legal marijuana in every state,” Trueblood said. “I think that’s fairly inevitable, even in very conservative places like Florida.”

Reider said his tribe plans to sell both medical and recreational marijuana. Minors will be allowed to consume pot if they have a recommendation from a doctor. Under a tribal ordinance passed in June, adults 21 and over will be able to buy one gram of marijuana at a time for recreational use, no more than twice a day.

“We really don’t want the stuff getting out to the street,” Reider said. “So we’re going to have like a bar setting where they’ll be able to consume small amounts while on the property.”

Kevin Sabet, president of the anti-legalization group Smart Approaches to Marijuana, said the California raid shows that it’s still “an extremely risky venture” for any tribe to start selling marijuana. And he said pot sales would fuel more addiction.

“If we think alcohol has had a negative effect on young people on tribal lands, we ain’t seen nothing yet,” Sabet said.

As part of his homework, Reider said, he traveled to Colorado, the first state to sell recreational pot last year. He said he does not smoke marijuana but has concluded that it’s safer than alcohol, citing the behavior he witnessed at the Cannabis Cup, a marijuana celebration held in Denver in April.

“It was a peaceful environment,” he said. “Everybody was overly friendly, overly talkative to each other and respectful of each other. Where if you go to a concert where there’s a lot of alcohol, you typically see fights and arguments.”

Reider said the tribe plans to begin growing 6,000 marijuana plants in October and is renovating a bowling alley to house a new consumption lounge that will include four private rooms. He said the tribe may consider allowing marijuana consumption in its casino in the future.

Reider acknowledged that it’s “kind of an awkward feeling” to start selling pot, but he figures the tribe is well-equipped.

“When we started looking into it, it’s comical at first, but then you realize it’s an amazing business,” he said. “It’s highly regulated, and we’re used to the regulation from operating our casino. We’ve got security and surveillance.”

Reider said profits from pot sales will be used to help tribal members. He said that could include the construction of a facility for those addicted to alcohol, prescription drugs or methamphetamine.

“We don’t have a recovery treatment center on the reservation right now,” Reider said. “Potentially we could look to fund one of those operations, and not just for marijuana addiction.”