Photo Courtesy of Noel Franklin.

By Micheal Rios, Tulalip News

Recently, the Seattle Art Museum presented PechaKucha Seattle volume 63, titled Indigenous Futures. PechaKuchas are informal and fun gatherings where creative people get together and present their ideas, works, thoughts – just about anything, really – in fun, relaxed spaces that foster an environment of learning and understanding. It would be easy to think PechaKuchas are all about the presenters and their presentation, but there is something deeper and a more important subtext to each of these events. They are all about togetherness, about coming together as a community to reveal and celebrate the richness and dimension contained within each one of us. They are about fostering a community through encouragement, friendship and celebration.

The origins of PechaKucha Nights stem from Tokyo, Japan and have since gone global; they are now happening in over 700 cities around the world. What made PechaKucha Night Seattle volume 63 so special was that it was comprised of all Native artists, writers, producers, performers, and activists presenting on their areas of expertise and exploring the realm of Native ingenuity in all its forms, hence the name Indigenous Futures.

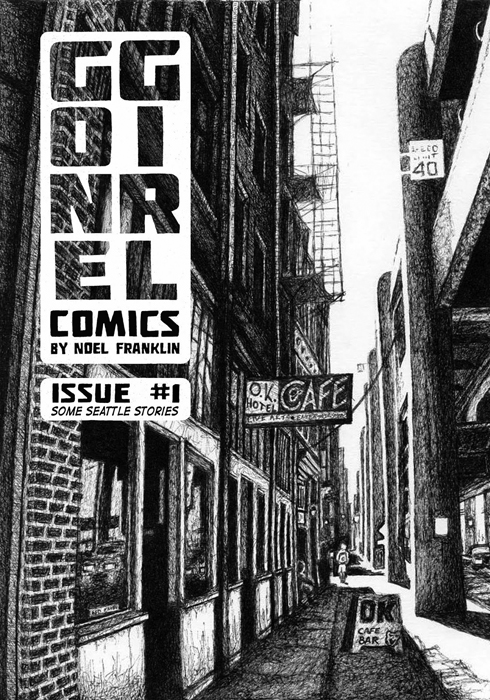

“If we are going to talk about Indigenous Culture, then we have to talk about representing ourselves. It is important for Native Americans to take over that part of representation. I do that through my comics.”

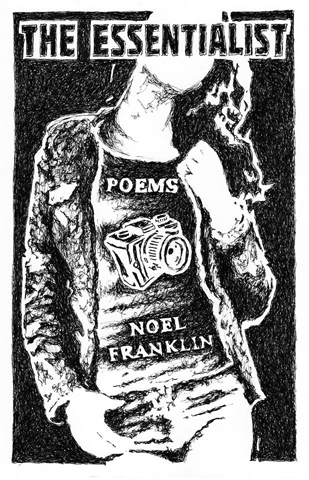

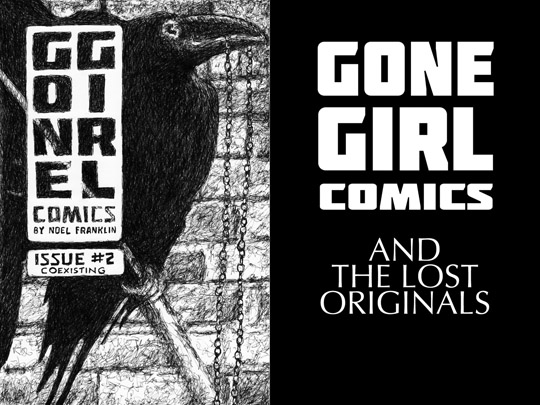

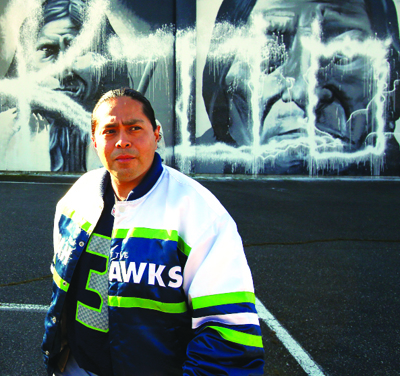

Noel Franklin is many things; a cartoonist, a print maker, a poet, a fundraiser and an activist. She worked with the United Indians of All Tribes Foundations, a foundation to serve as a focal point for the renewal and regeneration of Native Americans in the Greater Seattle area and beyond, to include the Northwest Native Canoe Center in the Lake Union Park masterplan. The Canoe Center will be an active cultural center where hands-on experiences teach visitors about Native American life while supporting the ongoing vibrancy of canoe culture traditions for present and future generations.

Noel’s comics have been published in more than five countries, and she is the first female artist to win the Emerald City Comic Con ‘I Heart Comics Art’ award. Noel’s current day job is at Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center.

“My father’s family is Eastern Band Cherokee and my mother’s family is from Scotland,” explains Noel. “My father joined the military like many male Native Americans, not too many options out there when you don’t have an education. I got to enjoy the poverty and intergenerational PTSD that so many of us are familiar with. As a youth I moved around so much because of the military that I was unable to really know my grandparents who spoke the Cherokee language and really lived their culture.”

Because of her father’s military career, Noel was constantly on the move from city to city. She was unable to make roots in any one location and felt isolated from her Native heritage. Her internal angst and loneliness would manifest itself on her canvas of choice, varying from paper for drawing and painting to stone-cold metal used for art welding.

“I art welded my way to a fine arts degree from Western Washington University,” says Noel. “Back then, in 1994, I didn’t think I knew who I was, but when I look back at my art I was painting and welding figures of crows, beetles and trees. I was talking to nature even though I didn’t know how to talk to nature. How did I know how to be Native when I was denied the ability? I continued to make art that reflected my pain of not knowing my own history and also the violence that came by growing up in a family that had multiple generations of post-traumatic stress disorder. However, I started learning about my Native culture and celebrating it as I learned.”

As she dedicated herself to learning about her Native heritage and the culture she was denied as a youth, Noel began to see the world differently. She looked at the world of art and representation through the eyes of a Native woman. She became self-conscious of a key theme that is prominent in the Native American resurgence; the misinterpretations of Native values and identity that act as continued colonization over Native peoples.

“So why do I now represent my culture through comics? Do you remember Peter Pan? I used to think I liked that movie, but as I grew older and learned of my heritage something changed,” recalls Noel. “I watched Peter Pan as an adult and was beyond offended at the ‘What Made the Red Man Red’ scene. I had to rethink a lot of things. If we are going to talk about Indigenous Culture, then we have to talk about representing ourselves. It is important for Native Americans to take over that part of representation. I do that through my comics.”

Noel attributes her unique style, building dark and light shapes from densely knotted lines, to her experience with stone lithography. She also feels that gutters between panels keep the viewer from total immersion in the world she invents in her stories. In addition to creating Gone Girl Comics, she is a regular contributor to inkart.org and has multiple journal and anthology publications. Presently, Noel is working towards creating her first graphic novel.

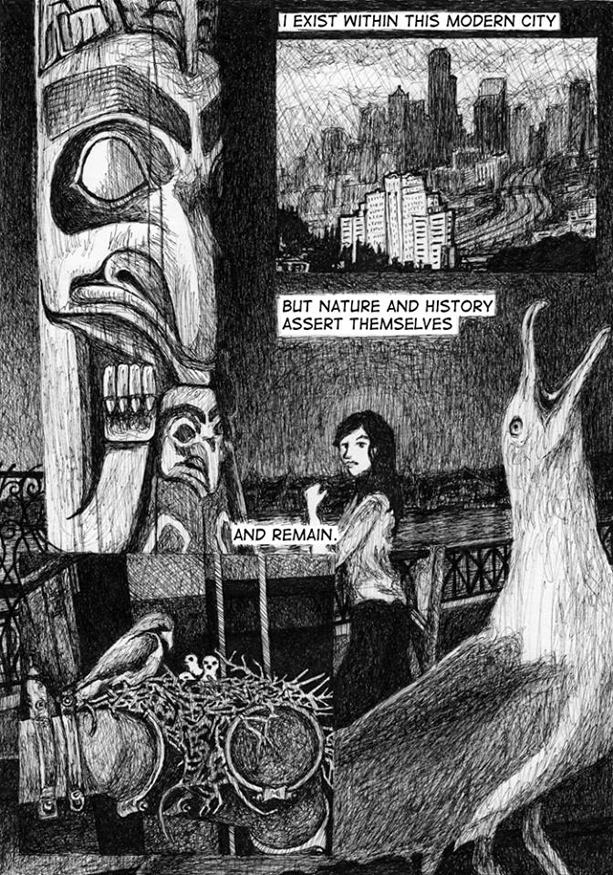

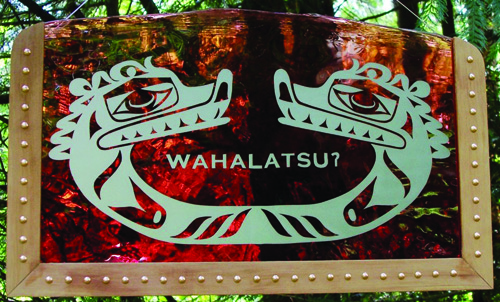

“Page four of a story called Seagulls Screaming is about how Native American culture is present and visible in Seattle,” said Noel. “Native American culture is not going anywhere. You might recognize the totem pole from Victor Steinbrueck Park, located just on the outside of Pike Place Market.

“If I can leave you with anything at all it’s this: we can shape the physical Seattle, but until we shape our own lives by owning our own representation and telling our own stories, which will strengthen not only ourselves but others, we’re going to end up with ‘Why Is the Red Man Red’ for the rest of our lives. I don’t know about you, but I’m not interested in that at all.”