By Jeanne Steffener, Tulalip Tribes Higher Education

Public libraries are strongly valued by Americans because they provide access to a range of materials and resources, promote literacy and improve the over quality of life in a community. In an economic impact-analysis that was recently conducted by Indiana University, public libraries reported a return of $2.38 to the community for every dollar of investment. In another similar study in San Francisco, it was found that $3.34 was the return for each dollar invested.

Over the years, communities have tried to measure the value that libraries provide through their collections (books, dvd’s, ebooks, magazines, etc.), programming, internet access, services to job seekers and businesses and other demonstrated economic return. Actually, the numbers do not really capture the total picture and it is very difficult to apply a specific dollar amount to the incalculable social good that libraries provide to a community.

We do know that a majority of Americans use their public library and in survey after survey we learn that approximately 71% of Americans think that libraries spend their money wisely. In fact, in a recent Pew Research Center survey a vast majority of Americans over 16 years of age said that public libraries play an important role in their community:

- 95% of Americans ages 16 and older said that materials and resources available at public libraries play an important role in giving everyone a chance to succeed.

- 95% said that public libraries are important because they promote literacy and a love of reading.

- 94% said that having a public library improves the quality of life in a community

- 81% said that public libraries provide many services people would have a hard time finding anywhere else.

Some of services that Americans strongly value in their public libraries include access to books and media; having a quiet, safe place to spend time, read or study; and access to librarians who are most willing to help people find the information they need. Libraries are particularly valued by those who are unemployed, retired, searching for a job, those living with disabilities, internet users who lack home internet services, students and moms with young children.

In a recent article in the Everett Herald, we learned about Joshua Safran who found out as a child that the Stanwood Library was more than a place to check out books. It was a refuge from the chaos of his life and an escape into books and the Dewey Decimal System1 that the librarians introduced to him. He is now a nationally recognized author, attorney and advocate for victims of domestic violence. In June of this year, he came back to the Stanwood Library, his childhood sanctuary to talk about his memoir “Free Spirit: Growing Up on the Road and Off the Grid”. http://www.heraldnet.com/article/20150627/ NEWS01 /150629263/Victims

This compelling story is an example of the impact our local public libraries imprint on our lives and communities in a strong, measureable way which cannot be equated to dollars and cents.

No Library card? Register for one at any library or online at www.sno-isle.org/getacard.

Get instant 24/7 access to most of Sno-Isle Libraries eResources.

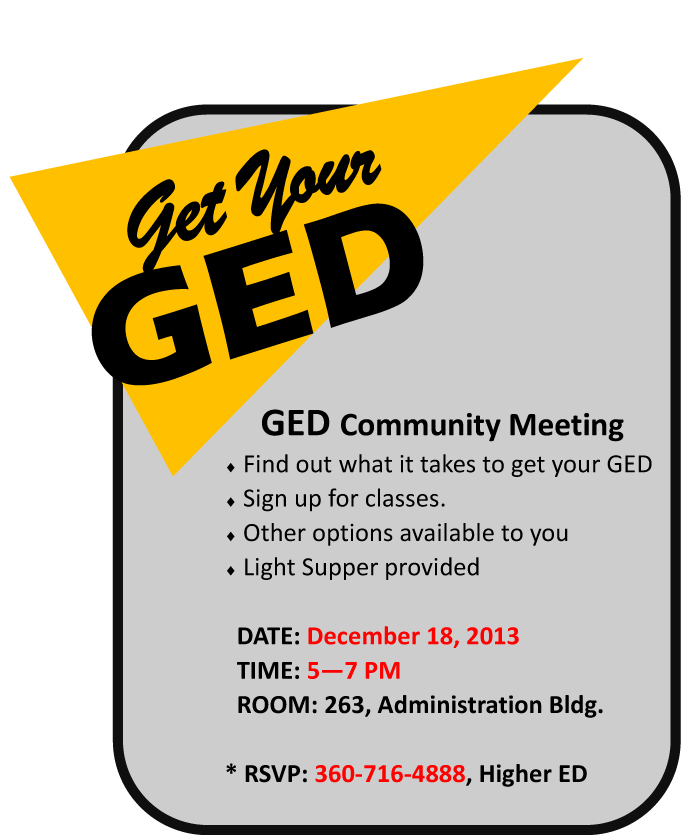

In August, we are having the Sno-Isle Libraries program Finding Customers with A to Z Databases. September’s offering is Twitter for Beginners. You can also check out monthly programming information on the Higher ED Webpage, on Tulalip TV and through information mailed to your home. You can call us at 360-716-4888 or email us at highered@tulaliptribes-nsn.gov for additional information.

1 Dewey Decimal System is a numerical classification system which allows new books to be added to a library in their appropriate location based on subject. The classification’s notation makes use of three-digit Arabic numerals for main classes, with fractional decimals allowing expansion for further detail. The number makes it possible to find any book and return it to its proper place on the library shelves.