A German museum dedicated to much-loved Wild West adventure author Karl May has gotten caught in a row with Native Americans over human remains in its display. The tribes have called for their return – to no avail.

Source: Deutsche Welle

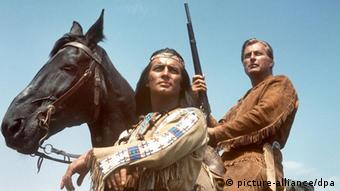

Germany’s fascination with the Wild West is largely down to one man – Karl May, the celebrated adventure author whose stories of Winnetou and Old Shatterhand fed the dreams of countless German children from the late 19th century on. The highpoint of his fame arrived in the 1960s with the still fondly-remembered movie adaptations.

Now the Karl May Museum in Radebeul outside Dresden has been caught in a row with two Native American tribes over a set of scalps in its display cases. Cecil Pavlat, cultural repatriation specialist of the Ojibwe Nation – to which one of the scalps is said to belong – wrote a letter to the museum earlier this month about the offense caused by the “insensitive display” of these “ancestral remains” – and asking for their return.

“It’s a part of that human being,” Pavlat told DW. “It’d be no different to cutting a hand off, or an arm and displaying that – it’s just not culturally appropriate or even acceptable by most ethnic groups, whether they’re Native American or not.”

Pavlat also sees the display itself as part of an age-old misrepresentation of Native Americans. “That’s the way we view it, as ancestral remains, even speaking the word ‘scalps’ – it creeps me out,” he said. “Some say that this was a practice created by our people. History tells us that this has been practiced throughout history in other places, including Europe.”

Tough negotiations

The museum got most of its collection of scalps from Karl May fanatic Ernst Tobis, an eccentric traveller and sometime acrobat who went by the pseudonym Patty Frank. The Austrian bequeathed his huge collection of Native American artifacts to the museum in 1926.

So far the museum has been cagey about responding to the requests, which go back further than Pavlat’s letter. Mark Worth, an American living in Berlin, was outraged when he first saw the scalps on display and brought the display to the attention of Karen Little Coyote of the Arapaho-Cheyenne Tribes in Oklahoma. She wrote a letter to the museum last fall. After correspondence with the US embassy, a cultural attaché from the Leipzig consulate went to the museum and, according to an e-mail she sent to Little Coyote later, handed over a copy of the letter in person.

Yet the US embassy, for its part, has largely left the matter to the tribes to deal with, recommending that the tribes contact the museum directly, and adding, in an e-mailed statement to DW, “The Consulate in Leipzig shared the information in the letter with the Karl May Museum earlier this year during the course of a meeting that touched upon a variety of other matters.”

Museum director Claudia Kaulfuss at first refused to acknowledge that any “official request” had arrived, but told DW: “In principle we are ready to talk, but first we want to understand what is wanted. We have four scalps on display, and it’s not even clear which tribes they belong to. We have two from white people, two from Indians – one of them is more or less just a plait of hair, and whether any really belongs to an Ojibwe Indian we don’t know.”

But the history of the Karl May Museum, published on the Karl May Foundation website describes in dramatic detail how Tobis bought the first of his scalps in 1904 – “the most sought-after collector’s item.” On a night-time trip to an Indian reservation, Tobis held “tough negotiations” with Dakota chief Swift Hawk, “who had won the scalp in a fight with an Ojibwe,” and bought the “trophy” for two bottles of whisky, a bottle of apricot brandy, and $1,100.

A piece of history

“We’re just showing a piece of history,” Kaulfuss told DW. “It’s an ethnological exhibition. We don’t want to falsify the history of the Indians in America.”

“Of course we’d enter into dialogue,” she added. “But we’d also want to put forward our side. We’re a museum in Germany, subject to German law, and we’d like to explain why we want to show a piece of history, and that we aren’t pillorying anything with it. But they can’t just expect us to hand something over without talking to anyone about it first, because then more people might come and soon our museum would be empty.”

Tugs-of-war between museums and indigenous cultures have become an issue in recent decades all over the world. The US passed the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA) in 1990, which forced federal institutions to return all “cultural items” to the relevant tribes. There was, moreover, a significant precedent only this month, when the University of Freiburg returned some 14 skulls to Namibia.

Worth thinks that human remains should hold a special position in such negotiations. “We should start with pieces of human beings. If we can’t agree that parts of human beings should go back to their families and communities, where are we?” he told DW. “That should be a minimum standard of dignity in this world.”

For some, it’s more disconcerting that the Karl May Museum is based around the work of an author who wrote the bulk of his fiction before he ever visited the US. As Worth put it: “It is fitting that the Karl May Museum – whose limited knowledge and false impressions of Native Americans have their foundation in fictional characters invented by someone who had spent limited time with Native Americans – is now claiming to know the best resting place for remains of Native Americans.”