Over the past month, the Mayday community space in Bushwick, Brooklyn, has been a buzzing organizational hub in the lead-up to the highly anticipated People’s Climate Mobilization taking place September 20-21 in New York City in advance of the U.N. special session devoted to climate change. But along with providing space and support for the march — including round-the-clock art-making of every conceivable sort — Mayday has also been the incubator for a large scale act of creative civil disobedience planned for lower Manhattan’s Financial District on the morning of Monday, September 22. Entitled Flood Wall Street, the centerpiece of the action is a massive sit-in intended to at once compliment, punctuate and radicalize the politics of the march itself.

Since the basics of the action were released early this month, social media buzz has turned into fever-pitch momentum, with high-profile figures like Naomi Klein, Chris Hedges, and Rebecca Solnit committing themselves to participate in various ways. Also involved is the Climate Justice Alliance, which first put out the call for disruptive direct action over the summer. As energy mounts and commitments roll in from individuals and groups, there is a palpable feeling among organizers that the Monday action has the potential to be an historic watershed, both in its projected scale and the boldness of its message: “Stop capitalism! End the climate crisis!” Potential participants are invited to sign an online “Pledge to #FloodWallStreet” in order to indicate what kind of role they will be able to play in the action.

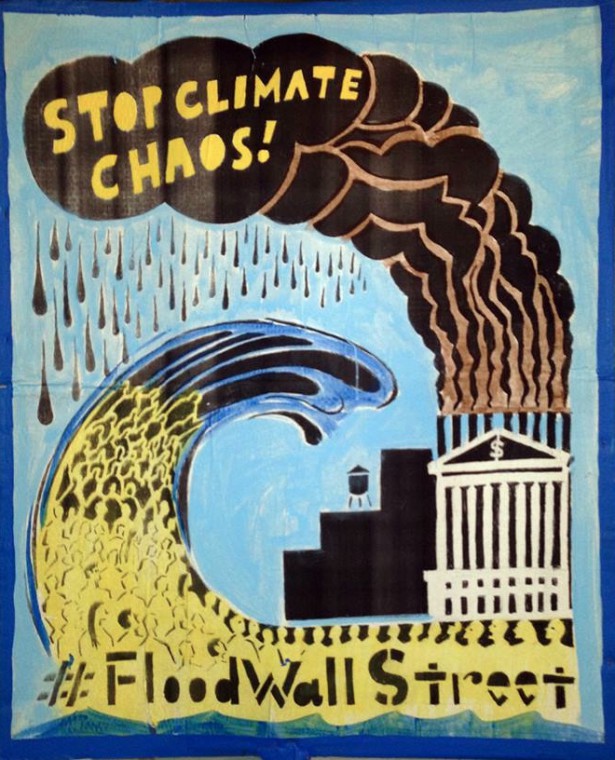

The symbolic logic of Flood Wall Street is evoked in a beautiful hand-crafted graphic by legendary illustrator Seth Tobocman emblazoned on dozens of signs, flags and banners fabricated during an enormous art-build at Mayday on Sunday: In the image, poisonous effluents ascend into the sky from an archetypical stock exchange building, forming ominous storm clouds emblazoned with the phrase “climate chaos.” The clouds, in turn, rain back into the sea, which surges back toward the land with a tidal wave of human bodies readable as both victims of apocalyptic disaster and agents of a popular storm surging toward the source of the emissions. At once a mythic vision and a simplified diagram of ecological feedback, the image is accompanied by the hashtag #FloodWallStreet.A poster made by Seth Tobocman.

The stakes of staging an action in the Financial District on September 22 become clear when understood against the backdrop of the People’s Climate Mobilization and some of the tensions surrounding it. This so-called “weekend to bend the course of history” has two primary components, the energies of which Flood Wall Street organizers hope to both draw upon and intensify in their action.

On the first day of the People’s Climate Mobilization, a distributed “climate convergence” — intended to develop grassroots education and cultivate movement networks — will take place at various sites around the city. This convergence is designed to set the stage for the Climate March on September 21, which is expected to draw over a hundred thousand people from around the country into a massive demonstration through midtown Manhattan. The march is a big-tent affair, with a lofty if generic “demand for action, not words,” addressed at once to the assembled leaders at the United Nations and to “the people who are standing up in our communities, to organize, to build power, to confront the power of fossil fuels, and to shift power to a just, safe, peaceful world.”

For all this talk of action, though, the march itself is designed as a traditional street protest, permitted by the New York Police Department with a predetermined route, marshals and barricades. As Chris Hedges pointed out in an inflammatory take-down of the “last gasp of climate liberals” earlier this month, the big organizations funding the march are determined to play it safe, ideologically and tactically. However, the march will provide a platform for groups like the Climate Justice Alliance that place economic and racial justice at the forefront of their organizing, linking the climate crisis to issues of displacement, housing, food sovereignty and solidarity economies. Further, as an aesthetic event, the march promises to be beautifully kaleidoscopic and poetically inspiring thanks to the artistic organizing efforts of the Sporatorium project headquartered at Mayday.

Finally, as with any large march, the possibility of autonomous actions, diversity of tactics, and unforeseen confrontations is high. All this said, however, the backbone logic of the march is one of appealing to the accountability of elected leaders, with a political horizon defined largely in terms of campaigns like fossil-fuel divestment and socially-equitable green jobs programs.

For the purposes of building a wide-ranging populist coalition aiming to bring thousands into the streets to place climate change at the center of the political landscape, these basic principles make a kind of lowest-common-denominator sense. But for many activists in a city that has over the course of the past three years undergone both the upheaval of Occupy Wall Street and the disaster of Hurricane Sandy, the People’s Climate March is, by itself, lacking the teeth necessary to confront the deeper nature of the emergency. “The climate crisis is not just a narrow ‘environmental’ problem of resources or jobs in need of better management,” Flood Wall Street organizer Sandra Nurse said. “It is the supreme symptom of a political and economic system that is bankrupt to its core.”

According to Nurse, the action will project “an explicitly anti-capitalist message” that can take advantage of whatever space is created by Sunday’s march. The setting for the two events is telling: While the one on Sunday is a permitted march through midtown Manhattan, Flood Wall Street is intended to be a disruptive direct action right at the front door of the climate criminals themselves.

At 9 a.m. on Monday, participants are invited to begin gathering at Battery Park just down from the iconic Wall Street bull. People are invited to wear blue and to bring blue materials of all sorts to enhance the visual narrative of a “flood” — including the possibility of a single gigantic blue banner visible from the sky. The brief programming during the gathering-period will involve food, music courtesy of Rude Mechanical Orchestra, and speakers from frontline communities, kicked off by 13-year-old artist-prodigy Ta’Kaiya Blaney of Sliammon First Nation and numerous members of the Climate Justice Alliance from around the world. Also scheduled to speak are high-profile writers like Naomi Klein, Rebecca Solnit and Chris Hedges. Following that will be a mass training session led by direct action specialists Lisa Fithian and Monica Hunken that will combine physical exercises with choreographed ritual intended to symbolically highlight the action-logic of the “flood” in advance of inundating the Financial District with bodies.

For obvious reasons, tactical details about the sit-in are under wraps, but an explicit call has indeed been made for it to occur at 12 p.m. What ultimately transpires is of course a wildcard, but the guiding intention is to stay put and to hold space.

“With the right numbers, the action has the potential to be a game-changer,” organizer Zak Solomon said. “Of all the times for folks to risk arrest, this is a historic occasion to do so with a massive base of support and visibility.” However, Solomon added, “Obviously not everyone is in a position to take an arrest. While no action is ever completely without risk, Flood Wall Street is designed to be inclusive, and to facilitate the participation and support of non-arrestable people, too. The key thing is to have a critical mass of bodies in the Financial District at a moment in which the whole world will be watching New York.

Speaking to this imperative of capitalizing on the global media presence expected in the city for that week, David Solnit, an artist and direct action veteran of the 1999 Seattle WTO protests, described Flood Wall Street as a “counter-spectacle” to the U.N. conference, one that will “intervene and disrupt the hollow public relations spectacle of Obama and the United Nations with the simple message: Corporate capitalism equals climate crisis.”

—

Flood Wall Street is an evocative metaphor for both ecological crisis and popular power. Yet it also has an uncanny resonance with the recent history of New York City. Indeed, a little more than two years ago, the Financial District was literally engulfed by floodwaters in a scenario that had otherwise seemed imaginable only in a Hollywood disaster fantasy. As evoked in a Flood Wall Street meme, the iconic Wall Street bull was in fact surrounded by seawater. Business was shuttered, power was knocked out, and the skyline went black — except for Goldman Sachs, which had its own private generator system. Strangely, then, the dream of “shutting down Wall Street,” frequently invoked by Occupy, was accomplished not through a massive blockade planned by humans, but rather by the unpredictable force of the global climate system. This era, which has been dubbed the Anthropocene, is one in which the elemental systems that life depends on — water, soil and the atmosphere itself — are fundamentally marked by the traces of human activity, organized according to the dictates of Wall Street.

Thus, while Hurricane Sandy was not a human action, neither can it be considered a “natural” event in any simple sense of the term — a philosophical and political conundrum explored by artist-organizers Not an Alternative in their recently-opened Natural History Museum project. In the words of Tidal magazine, Sandy was a “climate strike” in which, like Frankenstein’s monster, the unintended fruits of Wall Street’s drive for perpetual growth had come home to ripen. As diagrammed in Tobocman’s Flood Wall Street graphic, the carbon-saturated atmosphere doubled back upon those who had treated it as a dumping ground for what neoliberal economists describe as the “externalities” of capitalist progress. What had been treated as an externality — environmental destruction happening to the little people downstream from the centers of profit-making — was now internal to the system itself, with floodwaters literally pouring into the headquarters of the world’s leading financial institutions. The flooding of major urban centers does not bode well for the task of sustaining the global capitalist system, even if profits are certainly to be made along the way. It is clear to almost everyone that something has to change, but the question is by whom and for whom such changes will be made.

This is the question that looms over both the U.N. summit and the People’s Climate March itself. Koch brothers-style climate change denial remains rampant, and superficial corporate greenwashing is more pervasive than ever. But significant segments of the 1 percent are beginning to take climate change seriously, as both a source of risk to be mitigated and a source of profit-making to be mined, whether in the form of new insurance instruments, green luxury development schemes or energy-efficient technologies of all sorts. Indeed, a veritable rogues gallery of climate-profiteering CEOs will be gathering on the same afternoon as Flood Wall Street at the Morgan Library and Museum in midtown Manhattan for a strategic meet up of the Climate Group. Its mission is to foment “the clean revolution,” through what member Tony Blair describes as the group’s “unique ability to convene key business and government stakeholders, communicate the economic opportunities presented by bold climate action, and drive leadership.”

Obviously, the People’s Climate March generally presents a people-centered vision of economic development rather than the profiteering of the Climate Group, but the fundamental question posed by Sandra Nurse remains: “Will we take the climate crisis as an opportunity to reimagine the very meaning and structure of economic life itself, or devote our energies to the signing of treaties and the development of more efficient and humane forms of global capitalism?” As suggested by the popularity of books like Thomas Picketty’s Capital and Naomi Klein’s forthcoming This Changes Everything: Capitalism vs. the Climate, the triple blow of the 2008 crisis, Occupy and Hurricane Sandy in the past five years has helped make “capitalism” a viable object of public critique in the United States rather than the taken-for-granted horizon for all of social life.

The People’s Climate March is undoubtedly a historic occasion, but without the spur provided by direct action and a more comprehensive narrative concerning capitalism itself, it risks becoming a merely beautiful spectacle to match that of the United Nations, making us feel good about ourselves without pushing us beyond our comfort zones. Of course, Flood Wall Street runs this risk too, even if its tactics are planned to be more aggressive and its messaging more militant. For this reason, organizers within both the larger mobilization coalition and the Flood Wall Street team are already framing their work in terms of “after the march,” with the latter understood as a springboard for long-term climate justice organizing rather than a one-off day of action.

Such organizing will take on numerous forms, ranging from the mitigation and adaptation policy tools called for by groups like 350.org to exciting experiments that link fossil-fuel divestment efforts to reinvestment in locally-based, self-organized green economy networks in places like Jackson, Miss., and the Far Rockaways section of Queens. The concept of dual power is relevant here: It means not only forging alliances with diverse groups and supporting demands on existing institutions, but also developing counter-institutions of “commoning” that can provide support for resistance, while testing out forms of non-capitalist life in the face of ongoing crises.

Of all places, the Far Rockaways has pride of place as a reference in upcoming mobilizations. When the climate went on strike against Wall Street during Hurricane Sandy, the entire city paid the price — first and foremost in low-income communities of color with the least access to services, provisions and infrastructure. The dialectical counterpoint to the images of Wall Street underwater are those of physical destruction and human suffering in such areas — the monumental ruins of the Rockaway boardwalk, streets transformed into beaches, homes moldering and uninhabitable, darkened housing projects filled with stranded families. But at the same time, the Rockaways also has a landscape of people-powered relief, reconstruction and resistance that developed in the void of the state. Think of the You Are Never Alone community center, the relief hubs housed in churches overflowing with donations and volunteers, projects like the campaign against the Rockaways natural gas pipeline (which itself has actions planned for the weekend of the People’s Climate Mobilization), and the local chapter of the nation-wide community organizing Wildfire project, which is working long-term to develop sustainable grassroots economies in the face of both further climate disaster and the rapidly accelerating gentrification/displacement process on the peninsula.

The precarious conditions and multifaceted struggles of a place like the Far Rockaways epitomize the challenge of climate justice. According to the Climate Justice Alliance, “The frontlines of the climate crisis are low-income people, communities of color and indigenous communities… We are also at the forefront of innovative community-led solutions that ensure a just transition off fossil fuels, and that support an economy good for both people and the planet.” This is a concept that will strongly inform many of the activities of the climate convergence on September 20, including a special session of Free University NYC called “Decolonize Climate Justice” that will take place at the historic El Jardin community garden on the Lower East Side.

The educational session is devoted to approaching climate crisis through the “experiential lessons” of inequalities based in race, class and migration-status — both in terms of environmental damage, as well as the internal cultures of climate organizing itself: “The face of climate justice activism is often white, Western, middle class and male… As a result, the issues raised by such activism frequently exclude the urgent perspectives and priorities of those most impacted by climate change.”

Informed less by environmentalism as a narrow arena of concern than with a broader vision of collective liberation, the call to “decolonize climate justice,” issued by Free University places climate crisis in a deep sense of historical memory stretching back to the colonial violence at the origins of capitalism itself. This historical vantage point stands as a humbling challenge, and question, for an action like Flood Wall Street: How to use a mediagenic mass arrest as something more than a one-off disruption concerned with just the climate, but instead as a groundbreaking event for a continuous struggle-to-come encompassing landscapes of resistance ranging from the Rockaways to Ferguson to Palestine?

As demonstrated throughout the period of Occupy, taking an arrest in political action can be a radicalizing and life-changing event. But in taking this risk, those with the privilege and support to do so must not lose sight of the systemic violence of incarceration to which low-income communities of color are subject — the very communities that bear the brunt of environmental injustice. Without this level of analysis, the solidarity required for true climate justice cannot be built, and environmentalism risks fading back into the unexamined white, middle class sphere that has long defined it.

As the date approaches, consider the invitation: Come for the climate march, stay for the flood. And if you join the flood, be careful not to get swept away in the beauty of a single action. In the words of Talib Agape Fuegoverde, “May a thousand floods of the people sweep the land in coming years, washing away the walls and borders that capitalism erects to keep our struggles apart.”