By Tony Rizzo, The Kansas City Star

The tradition of Native American art is as rich and varied as the many tribes of North America.

And many collectors and aficionados willingly pay premium prices for it.

But that also makes buyers susceptible to counterfeiters — people willing to risk violating the federal law that prohibits non-Indian artists from marketing their creations as the handiwork of an Indian.

According to federal prosecutors, an Odessa, Mo., man did just that by falsely portraying himself as a Cherokee artist while selling his artwork online.

Federal prosecutors in Kansas City recently charged Terry Lee Whetstone, 62, with misrepresentation of Indian-produced goods and products, a misdemeanor that is punishable by up to a year imprisonment.

Neither Whetstone nor his lawyer responded to requests for comment, and he is not a member of the federally recognized Cherokee Nation, according to records of the Oklahoma-based tribe.

But he is an enrolled member of the Northern Cherokee Nation, according to Chief Kenn Grey Elk.

And while that nation is not federally recognized, it is officially recognized by the state of Missouri, according to Grey Elk.

That, according to Grey Elk, would qualify Whetstone as an Indian under federal law.

Federal prosecutors declined to comment about the charges beyond the information contained in court documents.

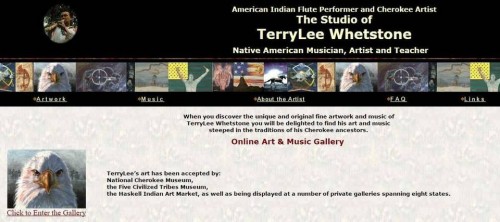

Whetstone’s website no longer functions. But for more than a decade, it cited his Cherokee heritage in advertising his music, painting, sculptures and jewelry.

He was raised in suburban Kansas City, according to his online biography, and performed flute music at numerous events around Kansas City. For years, his website claimed that his artwork could be found in many galleries and private collections — and even at The Smithsonian museum gift shop in Washington, D.C.

Federal prosecutors in Kansas City said they could not recall a similar case being filed in recent memory under the Indian Arts and Crafts Act of 1990.

But the phenomenon is enough of a problem nationwide that a special board under the auspices of the U.S. Department of the Interior has monitored the art world since 1935 to ensure that art marketed as Indian is authentic.

“While the beauty, quality, and collectability of authentic Indian art and craftwork make each piece a unique reflection of our American heritage, it is important that buyers be aware that fraudulent Indian art and craftwork competes daily with authentic Indian art and craftwork in the nationwide marketplace,” the Indian Arts and Crafts Board states on its website.

Federal law does not prevent non-Indians from producing Indian-style artwork. But only a member of an officially recognized Indian tribe, or a person certified as an Indian artist by a tribe, is allowed to market products as Indian-produced.

The law covers a variety of traditional and contemporary arts and crafts.

According to the Indian Arts and Crafts Board, items frequently copied by non-Indians include jewelry, pottery, baskets, carvings, rugs, Kachina dolls and clothing.

“These counterfeits undermine the market for authentic Indian art and craftwork and severely undercut Indian economies, self-determination, cultural heritage and the future of an original American treasure,” according to the Indian Arts and Crafts Board.

For legitimate Native American artists, the law is an important way to protect their cultural identity and livelihoods.

Counterfeiters “are appropriating a culture that’s not theirs,” said George Levi, an Oklahoma artist of Cheyenne-Arapaho descent.

Levi likened the crime to people who profit from counterfeiting the work of big-name fashion designers. Every piece of artwork sold as authentic by a non-Indian takes money away from a legitimate Indian artist, he said.

“They’re just trying to make a buck off of us,” Levi said.

The court documents filed in Whetstone’s case do not specify what type of artwork he sold.

But cached versions of the website listed in court documents featured his Indian-themed paintings and music. The site also showed pictures of Whetstone playing a flute and described him as a “self-taught, talented American Indian flute performer and multi-faceted artist.”

It said that he “reflects the history of his Cherokee heritage in his music and art.”

Last year, he received an award from the Indie Music Channel. In an award ceremony YouTube video, he identifies himself as “mixed-blood Cherokee.”

Whetstone listed his race as white on a 1997 Jackson County marriage license application that gave the option of marking white, black, American Indian or other.

For purposes of complying with the Indian art law, the artist must be an enrolled member of a tribe officially recognized by the federal government or a state. It is unclear whether Grey Elk’s assertion that Whetstone is a member with the Northern Cherokee Nation will have any impact on the federal case.

A person can be certified as a nonmember artist if they are “of Indian lineage of one or more members of a particular tribe,” and they have written authorization from the tribe’s governing body.

The Cherokee Nation carefully authenticates the tribal status of all artists whose work is displayed in galleries and gift shops, said Donna Tinnin, community tourism manager for the tribe.

Ensuring artwork’s authenticity is important for educating people about the specific traditions and history of each tribe, Tinnin said.

“Each tribe has their own story and their own styles of artwork,” she said.

Johnny Learned, president of the American Indian Center of the Great Plains, said he was glad to see the federal government taking action.

Learned said he finds it “interesting” that more people seemed to claim to be Indians as economic opportunities such as casinos expanded for Native Americans.

“I think there should be even more stringent rules that prohibit that,” he said.

Read more here: http://www.kansascity.com/news/local/crime/article25737253.html#storylink=cpy