foreignpolicy.com

VANCOUVER, Canada — On Canada’s western coast, where rain-forested mountains dip into gray-blue seas, the political anger is ready to explode. The indigenous people, whose ancestors have fished, hunted, and thrived here since the last ice age, are furious about an energy policy dreamed up in Ottawa that they fear could permanently damage their land and destroy their way of life.”Opponents can mock our love of our home as sentimental, but it won’t change what we feel,” the award-winning indigenous novelist Eden Robinson wrote recently in the Globe and Mail. “[T]he mood in our base is simmering fury.”

Robinson lives in Kitamaat Village, a small community some 400 miles north of Vancouver, near where the Kitimat River meets salt water. Its 700 indigenous inhabitants belong to the Haisla nation, one of 630 such recognized “First Nations” across Canada, which has called this coastal region home for thousands of years, going back to long before European settlers first arrived in the 18th century.

Lately the Haisla have had to reckon with a new unwelcome visitor: Calgary-based Enbridge, one of the world’s largest fossil fuel transporters. If the Northern Gateway project the company has been proposing for the past decade goes forward, a pipeline pumping 525,000 barrels per day of heavy crude from Alberta’s oil sands would end within walking distance of Robinson’s home. Tensions in her community are so high, she wrote, that “people will spit at you if they think you support Enbridge.”

It’s likely they will also spit at someone they think supports Canadian Prime Minister Stephen Harper. In June, his Conservative government approved the $7.3 billion Gateway project, which would ship oil across the Rocky Mountains to the Port of Kitimat, load it onto supertankers, and sell it for a premium to Asian markets. To reach the Pacific, supertankers must first navigate the winding Douglas Channel. In 2006, a provincial ferry crashed and sank in the channel, and people living in the nearby Gitga’at Nation village of Hartley Bay fear that history will repeat itself — but on a scale of environmental and cultural damage hard to fathom. They recently stretched a 2.8-mile crocheted rope in protest of Gateway across the Douglas Channel.

“Each stitch is shaped like a teardrop,” said blockade organizer Lynne Hill, “because this is a very emotional thing for us.”

“Each stitch is shaped like a teardrop,” said blockade organizer Lynne Hill, “because this is a very emotional thing for us.”

For Harper, Gateway promises a $300 billion GDP boost and the prestige of achieving his most important foreign-policy goal, to remake Canada into a global “energy superpower.” But to many First Nations living along the pipeline’s 731-mile-long route, Gateway symbolizes “everything that people don’t want,” Robinson said.

They intend to fight the pipeline in court by arguing for legal authority over land they’ve lived on for millennia and never surrendered to the federal government. A landmark decision from Canada’s Supreme Court on June 26 may have brought groups like the Haisla one step closer to achieving that authority.

Tension between indigenous people and the pipeline project are nothing new. In 2006, Enbridge sent surveyors, chain saws in hand, into the ancient forest near Kitamaat Village to scout sites for an oil terminal. They felled 14 trees that bore living evidence of First Nations history: deep notches made by the Haisla hundreds, or perhaps even thousands, of years earlier. “We compared it to a thief breaking into your house and destroying one of your prized possessions,” Haisla Councilor Russell Ross Jr. told me in 2012.

The relationship between the Haisla First Nation and Enbridge only got worse. Five years after the tree-cutting incident, the company offered a $100,000 settlement, which was “almost an insult” in the opinion of Chief Councilor Ellis Ross, as he stated in a letter to Enbridge’s president. Even worse was Enbridge’s additional offer to make amends with a “cleansing feast.” If such a ceremony was practiced widely in Haisla culture, Ross wasn’t aware of it.

“I have never witnessed Haisla Nation Council initiate a cleansing feast and I doubt I ever will,” he wrote to the firm. “I would appreciate it if your company’s shallow understanding of our culture is kept out of our discussions.”

All along the Gateway route, Enbridge was making similar cultural flubs. These gaffes, along with a negotiating style Robinson described as heavy on “talking points” and light on listening, had by 2011 caused 130 First Nations across British Columbia and Alberta to oppose the project, many of them not even directly impacted by it. “If Enbridge has poked the hornet’s nest of aboriginal unrest,” Robinson wrote, “then the federal Conservatives, Stephen Harper’s government, has spent the last few years whacking it like a pinata.”

The whacks began coming after Harper’s Conservatives won their first-ever majority rule in 2011. Since then, his Conservative Party has made it easier to get oil and gas projects approved, has cut environmental protections, and has proposed contentious changes to indigenous education. “It’s felt like the Conservatives have just been hammering us with legislation,” Robinson said. Tension with the Conservatives are so widely felt among First Nations that in late 2012 there emerged a protest movement called Idle No More, whose sit-ins, rallies, and hunger strikes brought national attention to the cause of indigenous sovereignty.

This May, a United Nations envoy deemed native distrust of Harper a “continuing crisis.” On Gateway, Harper has done little to ease the problem. After the U.S. rejection in early 2012 of TransCanada’s Keystone XL, a pipeline that was supposed to link Alberta’s oil sands to Texas, the prime minister “expressed his profound disappointment” to U.S. President Barack Obama, Harper’s office said in a statement. A week later, at the World Economic Forum, Harper vowed to export oil to Asia instead. Projects like Gateway were now a “national priority,” he declared.

For Harper, the economics of the project provide good reason for its priority status. Enbridge estimates that, once completed, Gateway would boost Canada’s GDP by $300 billion over the next three decades. Ottawa alone stands to gain $36 billion in taxes and royalties. And there is the issue of Canada’s role in the world. One month after the World Economic Forum, in February 2012, Harper traveled to China, where an influential crowd of Chinese business executives that Canada is “an emerging energy superpower” eager to “sell our energy to people who want to buy our energy.”

While Harper delivered that pitch in Europe and Asia, his then-natural resources minister, Joe Oliver (now finance minister), was declaring war on Gateway opponents back at home. In an open letter, Oliver lashed out at the “environmental and other radical groups” that in their protests against the pipeline project “threaten to hijack our regulatory system to achieve their radical ideological agenda.”

It was a tactical stumble, wrote George Hoberg, a University of British Columbia professor who studies the Gateway standoff, that pushed “many moderates who were offended by the style of the attacks into strong opponents of the pipeline.” Oliver’s letter was mentioned again and again during two years of federal hearings on Gateway, for which 4,000 Canadians registered to speak.

By the time those hearings finished last December, Gateway had become one of the top political issues in Canada. Much credit for that is due to a sustained media campaign coordinated by British Columbia’s major green groups, which deliberately evoked memories of Exxon’s 1989 Valdez disaster. On the spill’s 20th anniversary in 2009, they declared a “No Tankers Day.”

“There will be a sacrifice we’re asked to make at some point, and the [ecological] damage will be permanent,” said Kai Nagata from the Dogwood Initiative, one of the leading groups in that campaign. “Nobody’s come up with a compelling argument about why we should accept those risks.”

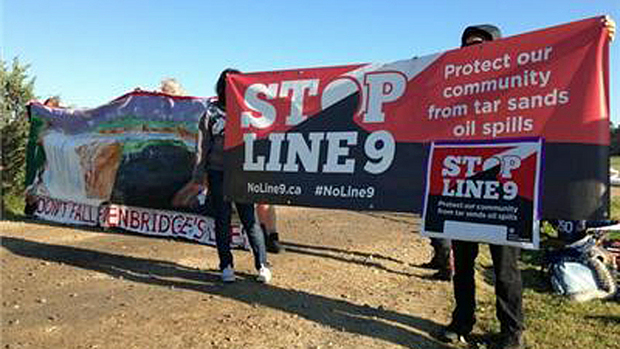

The continual focus on Gateway’s risks — to one of North America’s vastest wildernesses and to the indigenous people living within it — allowed green groups to broker alliances with First Nations all along the pipeline route. They appeared together at joint press conferences and waged a two-front opposition to Gateway so effective that, by this June, nearly 70 percent of people in British Columbia opposed immediate federal approval of the project, according to a Bloomberg-Nanos poll.

“The reason why Gateway has become such a political albatross for Stephen Harper,” Nagata explained, “is he’s managed to find a way to align the majority of British Columbians with the majority of First Nations.” Not to mention Vancouver’s mayor, British Columbia’s premier, and Harper’s political opponents in Ottawa, all of whom have spoken out against the project.

None of that opposition has deterred the federal Conservatives, though. In mid-June Harper’s government officially approved Gateway, deeming it “in the public interest.” Within hours of the announcement, a coalition of almost 30 First Nations and tribal councils in British Columbia were vowing to “immediately go to court to vigorously pursue all lawful means to stop the Enbridge project,” and promising that “we will defend our territories whatever the costs may be.”

Unlike in the United States, where indigenous peoples were conquered and then settled on reservations, few along Gateway’s proposed route have ever surrendered territory. What power they actually wield over that territory is legally disputed. Yet a Supreme Court decision on June 26 granting land title to the Tsilhqot’in First Nation gives greater legal standing to native groups with unresolved land claims.

The consequences of that decision, as well as the autonomy it ultimately provides to indigenous people, will be decided if groups like the Carrier Sekani Tribal Council, which represents eight First Nations across central British Columbia, challenge Gateway in court as unconstitutional. “What we’ll really be doing is testing our authority and our jurisdiction over the land,” said Terry Teegee, the council’s tribal chief. “It’s really hard to imagine this project going ahead.”

Enbridge is still confident. “We are prepared” for legal challenges, the company’s CEO, Al Monaco, said during a recent conference call, in which he contested the notion that people like Teegee speak on behalf of all First Nations. Monaco argued that 60 percent of indigenous people living along Gateway’s route in fact want to see it built (a claim called “ridiculous” by the Coastal First Nations group). Those court battles that First Nations do bring, in Monaco’s opinion, are likely to be resolved in Enbridge’s favor over the next 12 to 15 months. Gateway’s construction could begin shortly after. “This is not necessarily an endless process,” he said.

For indigenous people like Robinson, as well as the Unist’ot’en husband and wife now living in a wood cabin built intentionally along the pipeline’s path, the fight against Enbridge stands in for a larger cultural struggle. So long as companies and governments continue to view the rights of First Nations “as an impediment to getting what they want,” Robinson said, the struggle will surely continue.

Jennifer Castro/Flickr Creative Commons