Every day, aboriginal culture is borrowed, copied, dressed up or watered down. Is that art? Or is it stealing? Appropriation, it turns out, is all about the attitude.

By Samia Madwar

UpHere.ca June 1, 2014

Last fall, two exhibits opened in Montreal, both centred on aboriginal themes. Beat Nation, a multimedia presentation by aboriginal artists who’d mixed hip-hop culture with their own iconography, opened at the Museum of Modern Art on October 16. The next day—purely by unfortunate coincidence—the Museum of Fine Arts boutique unveiled Inukt, a new product line featuring aboriginally-flavoured clothing, accessories and homewares.

Beat Nation was an unapologetic, boundary-crossing exploration of tradition and modernity, and largely a critical success. Inukt was a confused, haphazard jumble, and a public relations disaster.

Like its mock, made-up name, few of Inukt’s products bear any resemblance to Inuit art. This April, the website advertised everything from T-shirts and tote bags to throw pillows and arm-chairs, adorned with portraits of random Plains Indian chiefs, bought from an online stock image gallery. Other T-shirts feature west-coast imagery—though the items themselves have Anishinaabe names. And then there are the “Eskimo doll” key-chains, miniature versions of embarrassing kitsch holdovers from a less sensitive time, their survivors now scattered across dusty thrift store shelves around the country. “The cultural mishmash here hurts my head,” wrote Chelsea Vowel, a Montreal-based Métis blogger.

Inukt’s designer, Nathalie Benarroch, is Canadian; a self-described fashionista who’d just returned to her home country after 23 years in Paris when she launched Inukt. “I saw this country with a totally new outlook than the one I had when I left,” she states on her website (inukt.com). “Canada is beautiful and has an overall good reputation, but it still lacked glamour … Hence came the idea to renew with the history, culture and codes of Canada, while reinterpreting them fashionably, giving them a contemporary edge and exposing choice artists and artisans that are the New Canada.”

Her attempt to glamourize, however well-intentioned, didn’t fly. In fact, it crash-landed pretty much out of the gate. Within hours of Inukt’s opening, Benarroch had received so much flak on her Twitter and Facebook accounts, many from First Nations critics, that she had to shut them down.

“Some people wrote whole tracts on [her social media accounts], explaining how exactly [Inukt’s products] encroached on their culture, and yet still Benarroch was uncomprehending,” says Isa Tousignant, the reporter who covered the controversy in the Montreal Gazette.

Five hours after Tousignant’s article was published, the museum boutique withdrew its Inukt products from sale. What went wrong? Lots, and Benarroch was only a small part of it.

The appropriation of aboriginal culture has been going on since first contact. In some ways, it’s part of living in a multi-cultural world; that’s why you don’t have to be Inuit to paddle a kayak, or First Nations to wear moccasins.

But there are limits. Sylvie Laroche, manager of Montreal’s Museum of Fine Arts boutique, claimed she didn’t see anything wrong with Inukt: “It’s tourist season now, and Europeans are nuts for this type of product,” she told The Gazette at the time.

“The free market idea doesn’t correspond to cultural responsibility in lots of ways,” says Tania Willard, curator of Beat Nation. “We can say people shouldn’t do that and it’s not respectful, but if people are buying it, that’s what’s going to happen.”

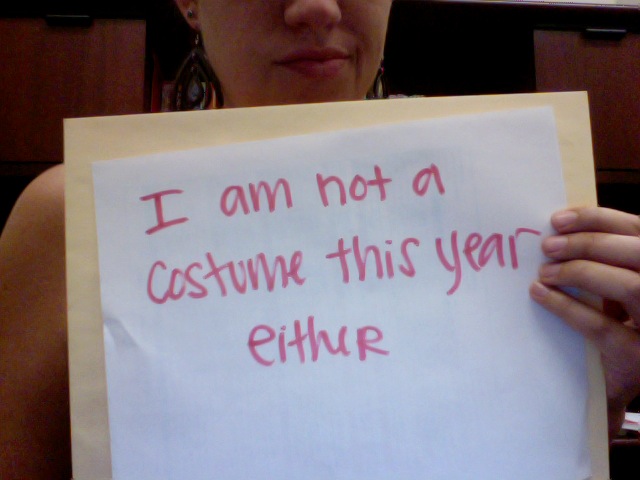

Inukt is hardly the worst offender. The headdress, a spiritual, sacred symbol for Plains Indians cultures, is one of the most controversial cultural objects out there. Headdresses are earned, not bought; eagle feathers are symbols of honour, and aboriginal activists in the U.S. compare warbonnets to army veterans’ medals. So when “hipster headdresses” became trendy, or when H&M Canada released a line of faux headdresses (featuring pink, green and purple feathers) last year, it was a problem. When Victoria’s Secret had lingerie models in headdresses in 2012, it was a problem. This past March, when cheerleaders at the University of Regina posted a photo to Instagram that revealed the team dressed as “cowgirls” and “Indians,” it was misappropriation, verging on racism.

Today, these transgressions don’t slip by without an uproar. “We have gone through the atrocities to survive and ensure our way of life continues,” Navajo Nation spokesman Erny Zah said in an interview following the Victoria’s Secret fiasco. “Any mockery, whether it’s Halloween, Victoria’s Secret—they are spitting on us. They are spitting on our culture, and it’s upsetting.” For the record, H&M withdrew their line with apologies. The cheerleaders were reprimanded and sent to cultural sensitivity classes. Victoria’s Secret also issued an apology, stating, “We absolutely had no intention to offend anyone.” Maybe so, but that naiveté is part of the issue. And Inukt is no exception.

“Canada uses aboriginal culture to sell itself or exotify itself,” says Tania Willard. “[Benarroch] said she was celebrating Canadian culture. And Canadian culture is in some ways an appropriation of aboriginal culture, and that’s a problematic history, and one that, today, we’re trying to right.” It’s not that non-native people shouldn’t be inspired by native art, says Willard. In fact, she has no harsh words for Benarroch herself. “The main thing there is to treat those designs with respect … and respect is acknowledging the original artist and acknowledging the original use of that work.”

With Inukt’s moccasins, Benarroch did manage to show some respect: she worked with Wendake, an aboriginal-owned business from the Huron-Wendat First Nation in Quebec, and mentions them on her website. Today, Benarroch says, she’s more sensitive to the issue: her latest designs lean away from First Nations symbols, instead using generic Canadian icons such as the maple leaf. (“Is that okay?” She asks plaintively when we speak on the phone.)

“That doesn’t mean other products in their line aren’t problematic,” says Willard. “I think the artwork [Inukt] is using for its clothing line should be properly credited as well. And I think they’d be more successful if they did that.”

It’s tricky. People take it for granted that aboriginal culture is free to imitate, steal and exploit. Then again isn’t that, rightly or wrongly, the way all culture evolves?

“Art is something we are inspired by and respond to, and we want that to be there,” says Willard. “I think that’s what makes art beautiful, the exchange in it. But how we do that—I think we can do that with a level of respect.”

But in the world of art, design and fashion, there are no rules. Lines are meant to be crossed. Should aboriginal culture, then, be off-limits?

Amautis, Inuit women’s coats featuring characteristically wide hoods to carry babies in, aren’t what most people would consider sacred, but in terms of cultural identity, they might as well be. Whether they’re made from seal, caribou or eider duck skins depends on the region, and a young mother’s amauti is different from that of a widow. For many Inuit seamstresses, the patterns they use are part of their family heritage.

So when Donna Karan, the fashion designer and creator of DKNY, sent representatives to the western Arctic in 1999 to buy up Inuit garments, including amautis—presumably to inspire a future fashion collection—a million red flags flew up. Until then, amautis hadn’t gone the way of the ubiquitous, mass-produced parka; for the most part, you could only buy authentic amautis in the Arctic.

Pauktuutit, a Nunavut organization representing Inuit women, launched a letter-writing campaign to Donna Karan. Putting designer amautis on the shelf, they said, would erode a vital Inuit artform.

It worked: DKNY never released an amauti collection. But the case raised some urgent questions. What if it happened again? For many Inuit seamstresses, making garments such as amautis is essential to their livelihood. In 2001, Pauktuutit launched the Amauti Project, establishing the garment as a case study on how to protect Inuit culture from future threats. The workshop concluded, “All Inuit own the amauti collectively, though individual seamstresses may use particular designs that are passed down between generations.”

That’s still not enough, legally speaking, to stop DKNY, or any other designer for that matter. Since 2001, Pauktuutit has focused on intellectual property law to protect cultural objects. But though it and other Inuit organizations are active in the World Intellectual Property Organization and have been lobbying for over a decade, it’s still the federal government that decides the official policy.

And the federal government’s position so far doesn’t help much. In response to a WIPO questionnaire on the protection of, among other things, aboriginal culture, in 2002, Industry Canada stated: “[Some] aspects of folkloric expressions, which are in the public domain, are available without restrictions and thus serve to enrich the fabric of Canada’s multicultural society.”

Since 2002, that hasn’t changed. Even if it does, it might only create more problems.

Tanya Tagaq defies tradition. A fiercely talented trailblazer from Cambridge Bay, Nunavut, she shook the world stage with her unique brand of throat-singing in 2001; since then, she’s collaborated with Bjork and the Kronos Quartet, and released two albums as well as a live recording (listen to her latest album, Animism, here).

While throat-singing is usually performed by two women, she sings solo. Her guttural energy has been labelled as primal, orchestral and free jazz. You wouldn’t want to restrict that. But despite her critical acclaim worldwide, not everyone back home approves.

“When I first started singing,” she says, “I was accused by fellow Inuit of appropriation.”

She was in her 20s. “I was putting it to music and doing it by myself, and there was a massive backlash … There were people who created a Facebook page to get me to stop. I heard Pauktuutit had a problem with me. All that was really hurtful.”

To her critics—most of them from an older generation, and, she adds, most of them never having been to one of her shows— she’d adulterated an artform that, like the amauti, is deeply rooted in Inuit culture. To Tagaq, what she’s doing is clearly not misappropriation: she is Inuk, and so her music is still Inuit art.

“I’m not trying to talk for everyone,” she says. “I’ve been though a lot of the stereotypical ideas of what Inuit people go through, so [throat-singing] is like protest music to me. I didn’t want to stand with a partner, nicely making some sounds … I don’t want to sound victimy to people.”

She recalls a non-Inuit woman from Cambridge Bay, Tagaq’s hometown, who grew up in the North and has taken up solo throat-singing. “I thought it was so cute,” Tagaq says, genuinely pleased. “If you’re from the North, that’s good. If you’re born and raised up there, and you’re part of the culture, then good, go ahead. But if you’re from Montreal and you’re just trying to sound cool, then no, that’s not OK.”

For artists venturing into aboriginal culture, “You need to make sure that you’re respecting the people,” she says, “and if one person [from that culture] has a problem with it, then it shouldn’t be done.” But what of her own critics?

Sometimes, she concedes, you can’t win. If her non-Inuit friend in Cambridge Bay had been the trailblazer, championing solo throat-singing, “I would’ve been fine with it,” says Tagaq. “But I think other people might not have been. The people who had a problem with me would’ve had a way bigger problem with her.”

To Jeneen Frei-Njootli, a young Vuntut Gwitchin artist from Old Crow, Yukon, the very idea of tradition is flexible. Consider what her own culture has adopted: coffee whitener, snowmobiles, fiddling. “Why can’t coffee whitener be a Vuntut Gwitchin food?”

There are some Vuntut Gwitchin stories she’d like to represent in her performances, installations and sculptures. But “because I don’t know them well enough, I am not allowed to use them,” she says. “That can also be counter-productive, because I’m a young person, I want to learn more about [these stories]. I want to interact with them and feel like they’re my own too. At this point, it’s really important to have as few barriers as possible for people who want to be knowledge-holders.”

Through her art, she hopes to lower those barriers. But being a cultural ambassador, she says, has its downsides. “It’s exhausting,” she says. As a student at Emily Carr School of Design, she often became the designated aboriginal expert, instead of getting to talk about her own work.

On a daily basis, she finds herself confronting people who, for instance, find it acceptable to wear feathered headdresses to parties. “How do you teach people the complexities of a situation … without alienating them? Talking about cultural appropriation in the bathroom of a bar is the worst way to learn.”

In the end, it shouldn’t be an artist’s burden to teach the world about cultural sensitivity. But for now, it’s emerging artists like Jeneen Frei-Njootli, established performers like Tanya Tagaq, and active curators like Tania Willard who are helping explore the boundaries of cultural appropriation and exchange, and nudging people toward the latter. At the same time, they’re challenging their own communities to embrace change. It’s up to the public to follow through.

Aboriginal culture “is not stagnant,” says Frei-Njootli. “It evolves and it grows. And I want to be a part of that.”