Slowly but surely, Seattle’s non-Natives have started to acknowledge the stories of the people who lived here before them, and are making exciting new history in the process.

For the 2015 edition of Best of Seattle, the Seattle Weekly staff looked back on the past year and selected the five innovations that we feel will do the most to make our city better. This is one of them. To read the rest of Seattle’s Best Ideas, go here.

When I call Matt Remle, he asks me to hold on for a second.

“I’m doing homework with my boy; I just have to tell him he gets a free break for a minute,” he says, chuckling. Remle, a Lakota man and the Native American Liaison at Marysville-Pilchuck High School, is often in the midst of homework, whether he’s helping students or his children or doing it for his own edification. As a Seattle correspondent and editor for the indigenous online news outlet Last Real Indians, he often digs deep into history. He aims to make connections to the present day in an attempt to tell stories that span centuries instead of moments, he says. In his mind, learning and telling stories about one’s ancestors is a necessary pursuit.

It’s a view he sees slowly trickling into the mainstream here in Seattle. “I think non-Natives are looking for a different voice and a different perspective,” he says.

Later today, Remle will visit Seattle City Hall to start planning the 2015 Indigenous Peoples’ Day celebration, a very new Seattle holiday he was instrumental in creating. Last September, Remle wrote the resolution and led the campaign to replace Columbus Day in Seattle with Indigenous Peoples’ Day—a motion unanimously passed in October by the Seattle City Council. During the campaign, Remle weathered personal attacks and phone calls from outraged opponents who claimed replacing Columbus Day was “focusing on the negative” and “preposterous.” The most intense opposition came from local Italian-heritage groups.

A drum circle gathered outside City Hall before the first hearing for the Indigenous Peoples’ Day resolution. GIF by Kelton Sears

During one of the initial September committee hearings on the resolution, Sons of Italy member Tony Anderson told the City Council, “I pray you observe the same courage Columbus did in that summer of 1492.”

The request was a curious one given the grisly history that Remle soon shared with the Council, which came from Columbus’ own journals.

The explorer’s records, along with the writings of the crew and the Spanish friar Bartolomé de las Casas who accompanied Columbus on that fateful voyage, detailed firsthand accounts of their brutal acts. Remle told of the enslavement, rape, torture, and genocide of the Arawak people they encountered in the summer of 1492. Beheadings of young boys “for fun”; lurid blow-by-blow tales of forced sex with 9- and 10-year-old girls, the casual day-to-day dismemberment of dozens of Arawak simply “to test the sharpness of their swords.” The list goes on. By the end of it, 80 percent of the Arawak people had been killed. These clearly were not the stories Anderson had heard.

He, like the rest of Americans who go to public school, was likely taught the cute rhyme most of us know: “In 1492, Columbus sailed the ocean blue.” The explorer met the “Indians,” “discovered” America, and brought back gold. He was a hero, the father of the great “New World.” As Anderson understood it, Columbus was courageous.

During Remle’s recitation of Columbus’ acts, one man at the committee hearing screamed, threw his hands up, and left the room. “That’s insulting! I’ve had it!” As the meeting adjourned, the same man cornered Remle in the council chambers and told him he should “get some education” and that his comments about Columbus were derogatory to Italians.

“When you question the prevailing narrative, people have this angry reaction,” Remle tells me. “For me, personally, when I started learning these histories that are swept under the rug and not taught, I was kind of pissed. I felt lied to. Maybe bringing the Native history in will open peoples’ eyes that there is another narrative out there.”

In the past year, people in Seattle, and in Washington at large, have also started to realize that, maybe, the stories they’ve heard about the places we live and the people that came before us aren’t the whole picture. Seattle’s historic passage of Indigenous Peoples’ Day was a celebrated international victory, making headlines in Europe and Canada—but it was met with some skepticism. A recurring question: Isn’t Columbus Day a trivial holiday anyways? Who cares?

If it actually was trivial, the passage of Indigenous Peoples’ Day probably wouldn’t have set off the wave of outraged and openly racist Internet comments, radio talk, and media coverage that it did. According to Tulalip Senator John McCoy, part of America’s difficulty with confronting its colonial history is that it’s ugly. Listening to indigenous stories is hard for non-Natives.

“A lot of the things that have happened to tribes, since European contact to today, are not pleasant,” McCoy says. “A lot of history books only talk about how the ‘bad’ Indians fought the settlers trying to tame the Wild West. But the Indians had to protect their land, their resources, because these folks were actually invaders. They weren’t explorers or pioneers, they were invading a country, a territory. Granted, there are some tribes that didn’t do nice things. But I always say that when you teach history, you have to teach the good, the bad, and the ugly.”

In 2005, McCoy, a member of the Tulalip tribe and the only Native in the Washington state senate, sponsored a bill mandating that Native history be taught in public schools. To his dismay, at the last minute, the legal language was changed from “mandatory” to “encouraged.” It took him 10 years of educating his fellow senators to muster the votes for a mandatory tribal-history bill—which he finally achieved this March in the landmark SB5433 (passed 42-7), making Washington the only state in the union besides Montana to require such instruction.

“I have a fellow Democrat, I won’t say who, that always fought me over tribal sovereignty,” McCoy says. “I got up to give my floor speech, and about a third of the way through, because he didn’t sit far from me, I actually heard him say ‘Oh, now I understand.’ ”

In addition to authoring legislation, McCoy also helped develop “Since Time Immemorial,” a free tribal-history curriculum with the help of Denny Hurtado, the now-retired director of Indian Education for the Washington State Office of the Superintendent of Public Instruction. Together, McCoy and Hurtado, who is of the Skokomish people, cover everything from the Coast Salish economies and governance systems before European contact and the early Indian boarding schools that forced cultural assimilation on tribal youth, through treaty-making, treaty-breaking, tribal sovereignty, and Indian relocation, all the way up to today’s urban Native issues, including indigenous activists’ increasingly vital role in environmental actions. In teaching Native history, the hope is that students will start to understand and recognize that there is also a Native present, that indigenous people aren’t just mythic figures in a fuzzy “pilgrims and Indians” past, but active participants alongside non-Natives in the crucial stories we are still writing—stories that directly affect everybody.

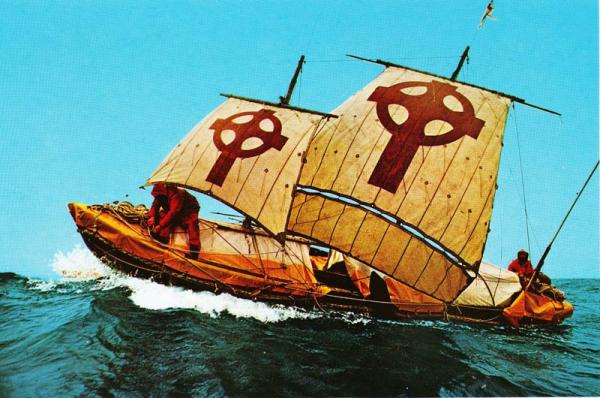

The ShellNo protest on May 16 was one of the most visible, widely covered environmental actions in the Pacific Northwest in decades, a feat for an area that’s long characterized itself as an aspiring ecotopia. The vivid pictures of the colorful kayaks rowing out to protest the imposing Shell Polar Pioneer rig set to drill in the Arctic captured the imagination of people from around the world who read headlines about “The Paddle in Seattle.” But it was the juxtaposition of the assembled, mostly white environmental groups with the fleet of traditional wooden canoes of the Lummi and Duwamish that cut the most striking image—a powerful flotilla led by the area’s original inhabitants.

“That’s the way it should go,” Duwamish Tribal Chair Cecile Hansen says. “If [environmental activists] are going to involve the Natives, they should be in the forefront.”

Idle No More, the indigenous activist organization that led the flotilla, gave the ShellNo action the spiritual weight that made it so resonant. Indigenous involvement reframed the discussion from an abstract issue about climate change to a concrete discussion that indigenous people have been trying to start for 500 years: the ongoing pattern of colonization and destruction committed in the name of resource extraction.

To Idle No More’s Washington state director Sweetwater Nannauck, the Tlingit/Haida/Tsimshian woman who organized the ShellNo action, it’s not a coincidence that Shell’s oil rig perched in the sacred Salish Sea was called “the Polar Pioneer.” “I was like, really?” she says, laughing quietly. “That’s what they named it? It continues the same old thing—another ship has come in. So that’s why I say it’s important for us to heal that, my work is as a healer. We’re both active participants in healing, the colonized and the colonizers too. The thing people are starting to see is, the original colonizers have become colonized—now it’s corporate colonization.”

Idle No More has reinvigorated the fight for climate justice in the state by making this very obvious but historically overlooked connection—environmentalists and indigenous activists are essentially fighting the same fight. The problem is that environmentalists have long tokenized Natives in the discussion, painting them as mystical Earth people—archetypal symbols from an imagined past—rather than actively engaging with them as people who exist in the present. Examples abound, from the famous 1970s “Keep America Beautiful” PSA featuring the iconic “crying Indian” (who was portrayed by an Italian actor) to the frequent citation of a moving environmental speech given by Chief Seattle in 1854: a speech that, oddly enough, references trains that wouldn’t be built until years later—perhaps because it was actually written in 1971 by a screenwriter from Texas.

Sweetwater Nannauck at ShellNo. Photo by Alex Garland

“A lot of the times, these organizations think allyship means ‘We’re going to organize everything, and we want you to send a couple of Natives to sing and dance and drum for us,’ ” Nannauck says. “That’s tokenism. I’m about authentically led Native action—we organize it. In the workshops I teach—which a lot of organizers like 350 Seattle, Rising Tide, Greenpeace, and Raging Grannies that participated in ShellNo have taken from me—I teach how to work with Native people, the history of colonization, and how that colonization continues to affect us today.”

“It was always very iffy for tribes to work with environmental organizations because these organizations were arrogant,” says Annette Klapstein, who participated in the ShellNo flotilla as part of the Seattle Raging Grannies. “They would tell tribes what to do, which didn’t go over very well. This new alliance, based on respect and understanding, is so important because these different groups’ goals are much the same, and we are so much more powerful together.”

In late October when the state held a hearing in Olympia to discuss the the impact that oil transport through the Northwest might have, Nannauck contacted the Nisqually, whose land would be most impacted, and organized a rally at the Capitol. After taking her Idle No More education workshops, in which Nannauck teaches non-Native activists how to respectfully work alongside Natives, organizers from the local environmental groups knew to contact the tribes first, asking if Idle No More had organized anything and if they could participate, rather than vice versa. The event was led with Native prayer and drumming that Nannauck and the tribes organized themselves, and Natives made the first testimonies at the rally, which eventually swelled to 350 people.

“I told Sweetwater this later,” Remle says. “ShellNo was one of the first actions of that size where I saw mainstream environmentalists take a back seat and let canoes and local tribes take the lead. It was pretty amazing to see.”

The most important component of Nannauck’s Idle No More workshops is communicating why indigenous activism differs from non-Native activism. Yes, both are fighting for the same goal, but there is a discernible difference in approach. Nannauck doesn’t even call what she does “activism.” Nor does Remle. They call it “protecting the sacred.” The ShellNo story wasn’t the typical angry diatribe pointed at distant oil corporations. As Nannauck puts it, the story that the ShellNo action told was about humanity’s obligation to protect the sacred Salish Sea.

“The work I’m doing is educating both Natives and non-Natives about how the cultural and spiritual work has much more of an impact, not only on the Earth, but because we need to heal ourselves,” Nannauck says. “What people need to understand is that the Earth is just a reflection of us, and that what we do to the Earth, we do to ourselves too. I try to educate them about our traditional ways and how that spiritual foundation is what motivates us.”

Nannauck ends her workshops by asking participants about their ancestors. Where did they come from? Did they benefit from the land grabs when they came to America? Were they also oppressed? If you go far back, were they colonized too? These are questions and stories non-Native audiences often haven’t considered. It’s hard to consider stories you didn’t know existed.

“A lot of people start crying because they can feel it,” Nannauck says. “Acknowledging that historical trauma, it’s kind of like a spiritual revival. It’s starting in the Northwest. I believe that’s what’s going on right now. I feel like what we’re doing here, what we’re starting here, could be replicated in other places. It’s not all negative—it’s about healing. It’s about the power of our spirit and our connection.”

ksears@seattleweekly.com