High Country News

News – From the February 18, 2013 issue

by Debra Utacia Krol

High Country News

News – From the February 18, 2013 issue

by Debra Utacia Krol

When the Obama administration announced in April that it would pay 41 tribes some $1 billion to settle a lawsuit over federal mismanagement of trust funds, many saw it as a sort of stimulus package for Indian Country — a chance to invest in long-term development and infrastructure, such as schools, clinics and roads.

“The seeds that we plant today will profit us in the future,” Gary Hayes, chairman of southwestern Colorado’s Ute Mountain Utes, told the Associated Press. “These agreements mark a new beginning, one of just reconciliation, better communication … and strengthened management.” His tribe, which received $43 million, initially planned to distribute about $2,000 to each of its 2,100 members, dividing the rest — about 90 percent — between the tribe’s general fund and investments. The Utes have long wanted to build a school on the reservation and improve health care.

But a few months later, Hayes was facing a recall election over the plan, and all the funds were being distributed on a per capita basis, under pressure from tribal members. The same response has echoed from tribe to tribe across the West — one that speaks to both the hard economic times and the lack of trust in leadership in Indian Country.

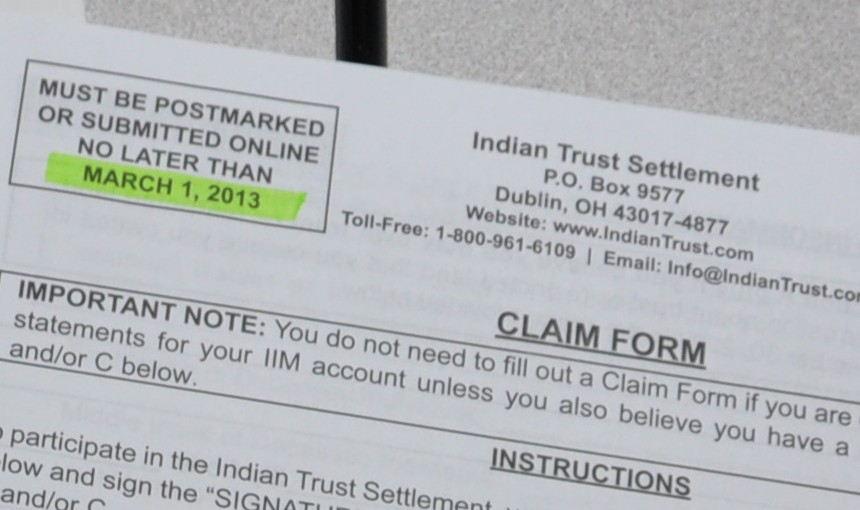

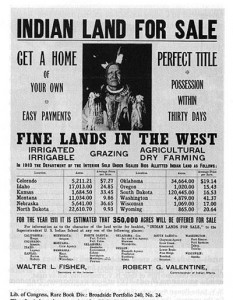

In 2006, 40 tribes joined Idaho’s Nez Perce in filing suit against the U.S. Department of the Interior, alleging a century of mismanaged trust funds and royalties for oil, gas, grazing and timber rights on lands held in common by tribal communities. It’s a different battlefront than the better-known class-action lawsuit filed by Montana Blackfeet leader Elouise Cobell, which represents individual Natives whose resources were mismanaged by the agency. The $3.4 billion settlement of the Cobell case authorized by Congress in 2010 is finally being resolved after being tangled up in the courts, but the resolution of Nez Perce et al. v. Salazar allowed checks to be issued relatively quickly.

As the funds began rolling in, however, conflict, not celebration, ensued. Nearly every tribe that had hoped to invest or save or otherwise spend the money has met with resistance from tribal members who prefer to see it distributed on a per capita basis. Some have used social media to make their point, campaigning on Facebook and Twitter to pressure leaders to “show us the money.”

It’s not surprising: Native communities are plagued by economic troubles, and a check for $10,000 or so can make a big difference to an individual or a family. According to U.S. Census figures, one in four Native Americans lives in poverty; nearly half the families in Hayes’ Ute Mountain Ute Tribe live below the poverty line. The prospect of that money vanishing into the coffers of a tribal government that may have a history of corruption understandably worries some tribal members.

Miriam Jorgensen, research director of the Native Nations Institute at the University of Arizona, says that the distrust over the settlements’ use is a two-way street. “Tribal citizens can find it hard to trust that their leaders will not use the settlement monies for personal or political gain, and leaders can find it difficult to trust that tribal citizens will not simply let the money slip through their fingers.”

Jorgensen likens the dilemma to the larger national discussion over taxes. “You want them cut or raised depending on the perceptions you have about how the money will be used,” she says. “But what is clear from both logic and research is that the tribal settlement monies, whether they are distributed to citizens or managed by tribal governments, will be of greatest use if they can be invested and spent in ways that generate benefits for the tribal community for years to come.”

The greatest beneficiaries so far are the Confederated Tribes of the Colville Reservation, a group of 12 tribes in eastern Washington, which received $193 million for mismanaged timber and range leases. Last summer, a major windstorm battered tribal forests, knocking down the equivalent of more than 2.5 million board-feet of lumber along with 200 power poles, and wildfires destroyed two families’ homes. The Colville Business Council had initially planned to use 80 percent of the settlement funds to restore the forests and to invest in other long-term projects, and disburse the remaining 20 percent, or about $4,000 to each of the 9,500 members.

But then Joanne Sanchez of Omak, Wash., a member of the Colville Tribe, decided that tribal members deserved a larger share. The recession has hit the reservation hard. In 2008, as the national economy was crashing, the two core local employers — a plywood manufacturing facility that also included a pilot power plant and the tribe’s lumber mill — shut down. Close to 700 jobs were lost in Omak, a community of about 3,500. “We have had hardship piled upon hardship,” says Yvonne Swann, 69, another tribal member fighting for distribution. Sanchez circulated a petition calling for a referendum on whether to distribute more funds to individuals and encouraged local media to cover the issue. Her efforts paid off: The tribe overwhelmingly supported the referendum. The tribal business council agreed to give each member another $6,100 in addition to the first payment. Now, about half of the total amount has been distributed.

“We’re at the lowest point economically, and we’ve been there for a while,” says Colville Business Council Chairman John Sirois, who has a master’s degree in public administration. “I can totally see why the people needed the extra funds — they need to pay bills that have been put off. They have medical bills.” The Colville Council still plans to use what’s left over for forest restoration and to mitigate the wildfires’ impacts on the land and water.

The original plaintiff in the case, the Nez Perce Tribe, distributed most of the $33.7 million it received to tribal members, but held back $3 million for the Native American Rights Fund, which handled the litigation.

And where are the millions paid out to individuals going? With a dearth of places to spend it in Indian Country, much of it appears to be stimulating the border town economy, instead. Take Cortez, Colo., an off-reservation town adjacent to the Ute Mountain Ute tribe, where total sales tax revenues increased by about 10 percent during the weeks when settlement checks of about $12,500 each were sent out. Car dealerships did especially well.

In the meantime, the conflict within other tribes continues. Swann, the Colville elder, is leading a charge there to get all of the money distributed. And in January, the 3,000-member Hoopa Valley Tribe in northern California voted to give themselves 100 percent of their $49.2 million settlement. Recently elected Councilman Ryan Jackson, who created a Facebook site to communicate with his constituency about the settlement and other issues, acknowledged that the central issue is “how the trust funds will be managed.” Jackson now plans to run for chairman.