“The tide is out and the table is set…” Justin Finklebonner gestures to the straits on the edge of the Lummi reservation. This is the place where the Lummi people have gathered their food for a millennium. It is a fragile and bountiful ecosystem, part of the Salish Sea, newly corrected in it’s naming by cartographers. When the tide goes out, the Lummi fishing people go to their boats—one of the largest fishing fleets in any Indigenous community. They feed their families, and they fish for their economy.

This is also the place where corporations fill their tankers and ships to travel into the Pacific and beyond. It is one of only a few deep water ports in the region, and there are plans to build a coal terminal here. That plan is being pushed by a few big corporations, and one Indian nation—the Crow Nation, which needs someplace to sell the coal it would like to mine, in a new deal with Cloud Peak Energy. The deal is a big one: 1.4 billion tons of coal to be sold overseas. There have been no new coal plants in the United States for 30 years, so Cloud Peak and the Crow hope to find their fortunes in China. The mine is called Big Metal, named after a Crow legendary hero.

The place they want to put a port for huge oil tankers and coal barges is called Cherry Point, or XweChiexen. It is sacred to the Lummi. There is a 3,500-year-old village site here. The Hereditary Chief of the Lummi Nation, tsilixw (Bill James), describes it as the “home of the Ancient Ones.” It was the first site in Washington State to be listed on the Washington Heritage Register.

Coal interests hope to construct North America’s largest coal export terminal on this “home of the Ancient Ones.” Once there, coal would be loaded onto some of the largest bulk carriers in the world to China. The Lummi nation is saying Kwel hoy’: We draw the line. The sacred must be protected.

So it is that the Crow Nation needs a friend among the Lummi and is having a hard time finding one. In the meantime, a 40-year old coal mining strategy is being challenged by Crow people, because culture is tied to land, and all of that may change if they starting mining for coal. And, the Crow tribal government is asked by some tribal members why renewable energy is not an option.

The stakes are high, and the choices made by sovereign Native nations will impact the future of not only two First Nations, but all of us.

How it Happens

It was a long time ago that the Crow People came from Spirit Lake. They emerged to the surface of this earth from deep in the waters. They emerged, known as the Hidatsa people, and lived for a millennia or more on the banks of the Missouri River. The most complex agriculture and trade system in the northern hemisphere, came from their creativity and their diligence. Hundreds of varieties of corn, pumpkins, squash, tobacco, berries—all gifts to a people. And then the buffalo—50 million or so—graced the region. The land was good, as was the life. Ecosystems, species and cultures collide and change. The horse transformed people and culture. And so it did for the Hidatsa and Crow people, the horse changed how the people were able to hunt—from buffalo jumps, from which carefully crafted hunt could provide food for months, to the quick and agile movement of a horse culture, the Crow transformed. They left their life on the Missouri, moving west to the Big Horn Mountains. They escaped some of what was to come to the Hidatsas, the plagues of smallpox and later the plagues of agricultural dams which flooded a people and a history- the Garrison project, but the Crow, if any, are adept at adaptation. The Absaalooka are the People of the big beaked black bird —that is how they got their name, the Crow. The River Crow and the Mountain Crow, all of them came to live in the Big Horns, made by the land, made by the horse, and made by the Creator.

A Good Country

“The Crow country is a good country. The Great Spirit has put it exactly in the right place; while you are in it you fare well; whenever you go out of it, whichever way you travel, you will fare worse… The Crow country is exactly in the right place.”

–Arapooish Crow leader, to Robert Campbell, Rocky Mountain Fur Company, c.1830

The Absaalooka were not born coal miners. That’s what happens when things are stolen from you—your land, reserved under treaty, more than 30 million acres of the best land in the northern plains, the heart of their territory. This is what happens with historic trauma, and your people and ancestors disappear – “1740 was the first contact with the Crow,” Sharon Peregoy, a Crow Senator in the Montana State legislature, explains. “It was estimated… to be 40,000 Crows, with a 100 million acres to defend. Then we had three bouts of smallpox, and by l900, we were greatly reduced to about l,750 Crows.”

“The 1825 Treaty allowed the settlers to pass through the territory.” The Crow were pragmatic. “We became an ally with the U.S. government. We did it as a political move, that’s for sure.” That didn’t work out. The 1851 Fort Laramie Treaty identified 38 million acres as reserved, while the 1868 Fort Laramie Treaty greatly reduced the reservation to 8 million acres. A series of unilateral congressional acts further cut down the Crow land base, until only 2.3 million acres remained.

“The l920 Crow Act’s intent was to preserve Crow land to ensure Crow tribal allottees who were ranchers and farmers have the opportunity to utilize their land,” Peregoy explains.

Into the heart of this came the Yellowtail Dam. That project split the Crow people and remains, like other dams flooding Indigenous territories, a source of grief, for not only is the center of their ecosystem, but it benefits largely non-Native landowners and agricultural interests, many of whom farm Crow territory. And, the dam provides little financial returns for the tribe. The dam was a source of division, says Peregoy.“We were solid until the vote on the Yellowtail Dam in l959.”

In economic terms, essentially, the Crow are watching as their assets are taken to benefit others, and their ecology and economy decline. “Even the city of Billings was built on the grass of the Crows,“ Peregoy says.

Everything Broken Down

“Our people had an economy and we were prosperous in what we did. Then with the reservation, everything we had was broken down and we were forced into a welfare state.”

–Lane Simpson, Professor, Little Big Horn College

One could say the Crow know how to make lemonade out of lemons. They are renowned horse people and ranchers, and the individual landowners, whose land now makes up the vast majority of the reservation, have tried hard to continue that lifestyle. Because of history of land-loss, the Crow tribe owns some l0 percent of the reservation.

The Crow have a short history of coal strip mining—maybe 50 years. Not so long in Crow history, but a long time in an inefficient fossil fuel economy. Westmoreland Resource’s Absaloka mine opened in 1974. It produces about 6 million tons of coal a year and employs about 80 people. That deal is for around 17 cents a ton.

Westmoreland has been the Crow Nation’s most significant private partner for over 39 years, and the tribe has received almost 50 percent of its general operating income from this mine. Tribal members receive a per-capita payment from the royalties, which, in the hardship of a cash economy, pays many bills.

Then there is Colstrip, the power plant complex on the border of Crow—that produces around 2,800 mw of power for largely west coast utilities and also employs some Crows. Some 50 percent of the adult population is still listed as unemployed, and the Crow need an economy that will support their people and the generations ahead. It is possible that the Crow may have become cornered into an economic future which, it turns out, will affect far more than just them.

Big Metal Mine, named after a legendary Crow (Courtesy Big Metal Coal)

Enter Cloud Peak

In 2013, the Crow Nation signed an agreement with Cloud Peak to develop 1.4 billion tons in the Big Metal Mine, named after a legendary Crow. The company says it could take five years to develop a mine that would produce up to 10 million tons of coal annually, and other mines are possible in the leased areas. Cloud Peak has paid the tribe $3.75 million so far.

The Crow nation may earn copy0 million over those first five years. The Big Metal Mine, however may not be a big money-maker. Coal is not as lucrative as it once was, largely because it is a dirty fuel. According to the Energy Information Administration, l75 coal plants will be shut down in the next few years in the U.S.

So the target is China. Cloud Peak has pending agreements to ship more than 20 million tons of coal annually through two proposed ports on the West Coast.

Back to the Lummi

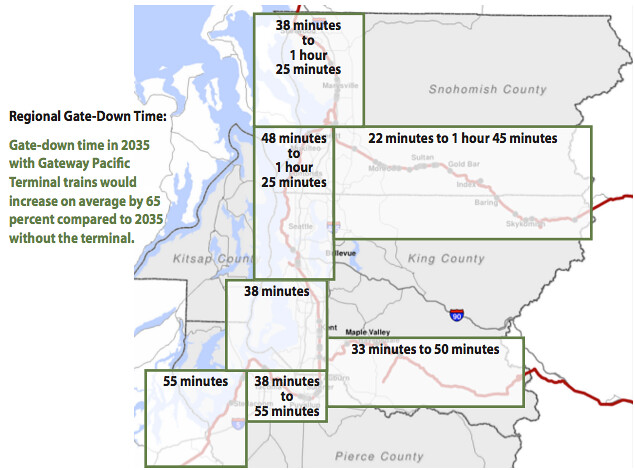

The Gateway Pacific Coal terminal would be the largest such terminal on Turtle Island’s west coast. This is what large means: an l,l00 acre terminal, moving up to 54 million metric tons of coal per year, using cargo ships up to l,000 feet long. Those ships would weigh maybe 250,000 tons and carry up to 500,000 gallons of oil. Each tanker would take up to six miles to stop.

All of that would cross Lummi shellfish areas, the most productive shellfish territory in the region. “It would significantly degrade an already fragile and vulnerable crab, herring and salmon fishery, dealing a devastating blow to the economy of the fisher community,” the tribe said in a statement.

The Lummi community has been outspoken in its opposition, and taken their concerns back to the Powder River basin, although not yet to the Crow Tribe. Jewell Praying Wolf James is a tribal leader and master carver of the Lummi Nation. “There’s gonna be a lot of mercury and arsenic blowing off those coal trains,” James says. “That is going to go into a lot of communities and all the rivers between here and the Powder River Basin.”

Is there a Way Out?

Is tribal sovereignty a carte blanche to do whatever you want? The Crow Tribe’s coal reserves are estimated at around 9 billion tons of coal. If all the Crow coal came onto the market and was sold and burned, according to a paper by Avery Old Coyote, it could produce an equivalent of 44.9 billion metric tons of carbon dioxide.

That’s a lot of carbon during a time of climate challenge.

Then there are the coal-fired power plants. They employ another 380 people, some of them Crow, and generating some 2,094 mw of electricity. The plants are the second largest coal generating facilities west of the Mississippi. PSE’s coal plant is the dirtiest coal-burning power plant in the Western states, and the eighth dirtiest nationwide. The amount of carbon pollution that spews from Colstrip’s smokestacks is almost equal to two eruptions at Mt. St. Helen’s every year.

Coal is dirty. That’s just the way it is. Coal plant operators are planning to retire 175 coal-fired generators, or 8.5 percent of the total coal-fired capacity in the U.S., according to the Energy Information Administration. A record number of generators were shut down in 2012. Massive energy development in PRB contributes more than 14 percent of the total U.S. carbon pollution, and the Powder River Basin is some of the largest reserves in the world. According to the United States Energy Information Administration, the world emits 32.5 billion metric tons of carbon dioxide each year. The Crow Tribe will effectively contribute more than a year and a half of the entire world’s production of carbon dioxide.

There, is, unfortunately, no bubble over China, so all that carbon will end up in the atmosphere.

The Crow Nation chairman, Darrin Old Coyote, says coal was a gift to his community that goes back to the tribe’s creation story. “Coal is life,” he says. “It feeds families and pays the bills…. [We] will continue to work with everyone and respect tribal treaty rights, sacred sights, and local concerns. However, I strongly feel that non-governmental organizations cannot and should not tell me to keep Crow coal in the ground. I was elected to provide basic services and jobs to my citizens and I will steadfastly and responsibly pursue Crow coal development to achieve my vision for the Crow people.”

In 2009, 1,133 people were employed by the coal industry in Montana. U.S. coal sales have been on the decline in recent years, and plans to export coal to Asia will prop up this industry a while longer. By contrast, Montana had 2,155 “green” jobs in 2007 – nearly twice as many as in the coal industry. Montana ranks fifth

in the nation for wind-energy potential. Even China has been dramatically increasing its use of renewables and recently called for the closing of thousands of small coal mines by 2015. Perhaps most telling, Goldman Sachs recently stated that investment in coal infrastructure is “a risky bet and could create stranded assets.”

The Answer May Be Blowing in the Wind

The Crow nation has possibly l5,000-megawatts of wind power potential, or six times as much power as is presently being generated by Colstrip. Michaelynn Hawk and Peregoy have an idea: a wind project owned by Crow Tribal members that could help diversify Crow income. Michaelynn says “the price of coal has gone down. It’s not going to sustain us. We need to look as landowners at other economic development to sustain us as a tribe. Coal development was way before I was born. From the time I can remember, we got per capita from the mining of coal. Now that I’m older, and getting into my elder age, I feel that we need to start gearing towards green energy.”

Imagine there were buffalo, wind turbines and revenue from the Yellowtail Dam to feed the growing Crow community. What if the Crow replaced some of that 500 megawatts of Colstrip Power, with some of the l5,000 possible megawatts of power from wind energy? And then there is the dam on the Big Horn River. “We have the opportunity right now to take back the Yellowtail Dam,” Peragoy says. “Relicensing and lease negotiations will come up in two years for the Crow Tribe, and that represents a potentially significant source of income – $600 million. That’s for 20 years, $30 million a year.”

That would be better than dirty coal money for the Crow, for the Lummi, for all of us.