BY STEPHEN QUIRKE, Earth Island Journal

Indigenous struggles against resource extraction are gathering strength in the Pacific Northwest

Under the breaking waves of Lummi Bay in northwest Washington, salmon, clams, geoducks and oysters are washed in rhythmic cascades from the Pacific Ocean. Just north of here is Cherry Point, home for three intimately related threatened and endangered species: herring, Chinook salmon, and orcas. It is also the home of the Lummi Nation, who call themselves the Lhaq’temish (LOCK-tuh-mish), or the People of the Sea. The Lummi have gone to incredible lengths to protect the health of this marine life, and to uphold the fishing traditions that make their livelihood inseparable from the life of the sea — continuing a bond that has connected them to the salmon for more than 175 generations.

Photo by Nicholas Quinlan/Photographers for Social ChangeThe Lummi Nation is currently fighting a proposal to build the largest coal export terminal on the continent at Cherry Point.

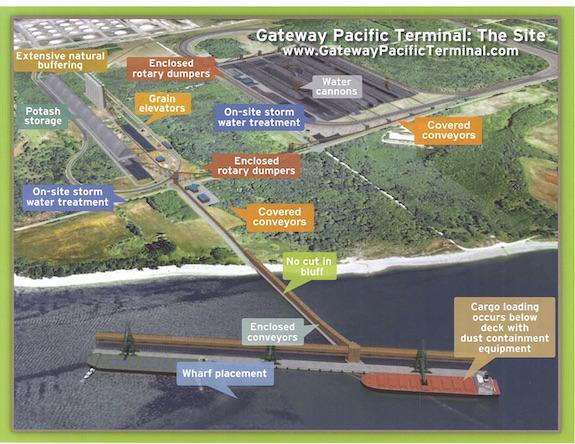

The Lummi Nation is currently fighting the largest proposed coal export terminal on the continent (read “Feeding the Tiger,” EIJ Winter 2013). If completed, the Gateway Pacific Terminal would move up to 54 million tons of coal from Cherry Point to Asian markets every year. The transport company BNSF Railway plans to enable the terminal by adding adjacent rail infrastructure, installing a second track along the six-mile Custer Spur to make room for coal trains.

The project is one of many coal export facilities proposed across the US by the coal extraction and transportation industry. In the face of falling domestic demand for the highly polluting fossil fuel, the industry is pinning its survival on exporting coal to power hungry Asia, especially China.

The Gateway proposal has sparked massive opposition from the Lummi, who say it will interfere with their fishing fleet, harm marine life, and trample on an ancient village site that has been occupied by the Lummi for 3,500 years. The village, Xwe’chieXen (pronounced Coo-chee-ah-chin) is the resting place of Lummi ancestors, and contains numerous sacred sites that the Lummi assert a sacred obligation to protect. The Lummi’s connection to their first foods, and to the village site that holds their ancestors’ remains, goes the very heart of who they are as a people, and the Nation has pledged to protect both “by any means necessary”.

The Lummi are no strangers to stopping harmful development. In the mid-1990s they managed to stop a fish farm in the bay; in 1967 they fought back a magnesium-oxide plant on Lummi Bay that would have turned the bay lifeless with industrial waste.

This article is part of our series examining the Indigenous movement of resistance and restoration.

The new threat to the Lummi Nation is being proposed by the global shipping giant SSA Marine. The coal would be supplied by Peabody Energy and Cloud Peak Energy — companies that mine in Montana and Wyoming’s Powder River Basin. It was also backed by Goldman Sachs until January 2014, when the company pulled its substantial investment from the project.

Jay Julius, a fisherman and Lummi Nation council member had attended the firm’s annual shareholders meeting back in 2013 and urged it to “take a look at the risk” of their investment.

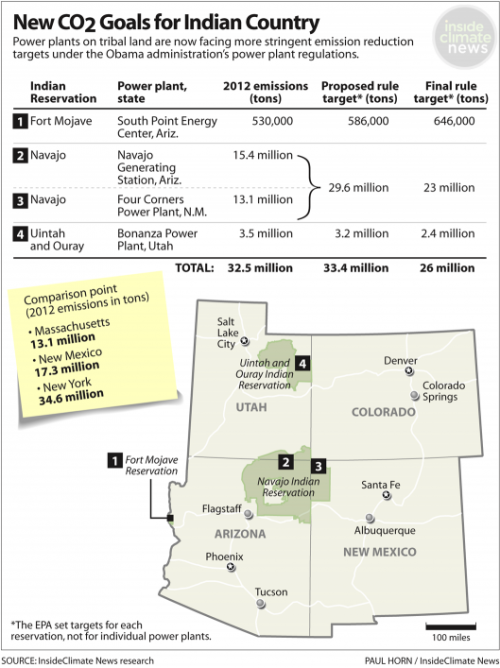

Another coal export proposal of similar scale has been proposed in Longview, Washington about 235 miles south from Cherry Point. This has been opposed by the Cowlitz Tribe, who object to the impacts that coal would bring to the air and water quality along the Columbia River. This terminal would also create serious harm to another Native tribe at the point of extraction, 1,200 miles away in the Powder River Basin.

The Millennium Bulk Terminal in Longview is a joint proposal from the Australia-based Ambre Energy and Arch Coal, the US’ second largest coal producer after Peabody.

The terminal, which would export up to 48.5 million tons of coal annually, would be supported by Arch Coal’s proposed Otter Creek Mine in southeastern Montana (bordering Wyoming). If built, the mine could produce an estimated 1.3 billion tons of coal, and would span 7,639 acres along the eastern border of the Northern Cheyenne Indian Reservation. This would be the largest mine ever in the United States.

Photo by Mike Danneman Coal trains operated by BNSF would haul coal from the Powder River Basin in Wyoming and Montana to a series of proposed export terminals along the Pacific Northwest coast.

To connect the proposed mine to West Coast ports, Arch Coal and BNSF Railway want to build a new 42-mile railroad — called the Tongue River Railroad — through the Northern Cheyenne Indian Reservation. Members of the Northern Cheyenne Nation and their allies have pledged fierce resistance if regulators approve the mine and the railroad, which they say, would have significant impacts on public health and the environment. According to BNSF, anywhere from 500 pounds to 1 ton of coal can escape from a single loaded rail car – on trains pulling 125 cars.

At a June hearing on the railroad organized by the US Surface Transportation Board, federal regulators heard nothing but fierce opposition to the proposed mine and its enabling railroad. A significant proportion of the Lame Deer community from the Northern Cheyenne Reservation turned out to the hearing. Their opposition to the project was echoed by local ranchers.

One rancher told the officials that they needed to understand the importance of history when they propose such unprecedented projects. “Northern Cheyenne history is very sad – it’s tragic – and they have fought with blood to be where they are tonight.”

“My ancestors have only been buried here for about four or five generations,” he said, but “we know of lithic scatters, we know of buffalo jumps, we know of stone circles, camp sites, vision quest sites… and it is my obligation as a land owner, even though I am not a member of this Nation, that we protect what is there.”

One tribal member, Sonny Braided Hair, was more explicit in his history lesson. “Let us heal,” he said, “or we’ll show you the true meaning of staking ourselves to this land.” He was referring to the Cheyenne warrior society known as the Dog Soldiers, who became legendary in the mid-1800s for holding their ground in battle by staking themselves to the earth with a rope tied at the waist.

Such concerns about sacred sites are too often validated. In July of 2011, before applying for any permits, SSA Marine began construction at a designated archeological site in the ancient Lummi village at Cherry Point, where the Lummi have warned of numerous sacred sites, and where 3,000 year-old human remains have been found.

Pacific International Terminals had earlier promised the Army Corps of Engineers that this site would not be disturbed, and that the Lummi Nation would be consulted before any construction began nearby. They also acknowledged their legal obligation to have an archaeologist on staff when working within 200 feet of the site, along with a pre-made “inadvertent discovery” plan if any protected items were disturbed. Despite all of these assurances, the company illegally sent in survey crews to make way for their terminal, where they drilled about 70 boreholes, built 4 miles of roads, cleared 9 acres of forest, and drained about 3 acres of wetlands.

In August, Whatcom County, Washington, (where Cherry Point is located) issued a Notice of Violation to Pacific International Terminals, and the Department of Natural Resources documented numerous violations of the state Forest Practices Act. The total fines and penalties, however, added up to only about $5,000.

That’s a small price to pay for early geotechnical information, says Philip S. Lanterman, a leading expert on construction management for such projects. According to Lanterman, the information provided by those illegal boreholes was probably a huge economic benefit to the planned project. Needless to say, the meager fines don’t come close to discouraging the behavior. For opponents this incident is just a taste of things to come, and one resounding reason to never trust King Coal.

In the face of such blatant violations of their treaty rights, several Native tribes in North America — from the Powder River Basin, through the Columbia River to the Salish Sea —have banded together and declared that it is their sacred duty to protect their ancestral territories, sacred sites, and natural resources.

In May 2013, the Affiliated Tribes of Northwest Indians (ATNI) unanimously adopted a resolutionopposing fossil fuel extraction and export projects in the Pacific Northwest. In the resolution, the 57 ATNI Tribes of Oregon, Idaho, Washington, southeast Alaska, Northern California, Nevada and Western Montana voiced, “unified opposition” to investors and transporters and exporters of fossil fuel energy, “who are proposing projects in the ancestral territories of ATNI Tribes.” The resolution specifically calls for protection of the Lummi Nation’s treaty-protected fishing rights, and the sacred places that would be affected by the Cherry Point project.

Indigenous resistance to these projects has been bolstered by allies in the environmental movement who have been fighting the export of US coal to foreign markets in the East. Of 15 recent proposals to build major new coal export facilities across the US, all but four (including Gateway and Millennium) have been defeated or canceled within the past two years.

In January this year, the Lummi Nation asked the Army Corps to immediately abandon the environmental review for Gateway Pacific and the Custer Spur rail expansion, stating that the project violates their reserved and treaty-protected fishing rights. If the environmental review is abandoned, the Army Corps would have effectively cancelled the project. In response to this letter the Army Corps gave SSA Marine until May 10 to respond, but later extended the deadline by another 90 days. Environmental reviews of the terminal and BNSF’s Custer Spur rail expansion are due in mid-2016, but it appears likely that the Army Corps will have rejected the Gateway Pacific terminal by then, rendering any rail expansion redundant.

Photo courtesy of Sierra ClubIn 2013, James launched a totem pole journey to build solidarity for Indigenous-led struggles against fossil fuels, including the struggle to protect Xwe’chieXen. Pictured here, ranchers, environmentalists, and members of the Northern Cheyenne totem pole blessing ceremony in Billings, Montana.

In order to keep the pressure on, leaders from nine Native American tribes gathered in Seattle on May 14 to urge the Army Corps to deny permits for SSA Marine. “The Lummi Nation is proud to stand with other tribes who are drawing a line in the sand to say no to development that interferes with our treaty rights and desecrates sacred sites,” said Tim Ballew II, Chair of the Lummi Indian Business Council. “The Corps has a responsibility to deny the permit request and uphold our treaty.”

The Lummi have clearly had important successes in stopping harmful development in the past. But with so much on the line for coal companies, can they really use treaty rights to stop a coal terminal of this size? “Without question,” says Gabe S. Galanda, a practicing attorney specializing in tribal law in Washington State. “Indian Treaties are the supreme law of the land under the United States Constitution, and Lummi’s Treaty-guaranteed rights to fish are paramount at Cherry Point.” If the Army Corps decides to deny their permit, Galanda says that coal developers would find it “very difficult if not impossible” to successfully challenge them. By contrast, he says, “the Lummi Nation would have very strong grounds to attack and invalidate” any approval that the Army Corps might grant to the coal exporters.

In a similar case last year, Oregon’s Department of State Lands denied a key building permit for Ambre Energy’s coal export terminal project in Boardman, Oregon. The terminal was planned directly on top of a traditional fishing site of the Yakama Nation. In both Boardman and Cherry Point, the coal companies have implied that the protected Indigenous sites that would be harmed by their projects either do not exist, or that the tribes using them are too incompetent to know their true location.

Just two years after filing paperwork with Whatcom County admitting that they had “disturbed items of Native American archeological significance”, Bob Watters of SSA marine wrote “Claims that our project will disturb sacred burial sites are absolutely incorrect and fabricated by project opponents.”

One of the Cherry Point Terminal’s most fierce opponents is the diplomat, land defender and master carver Jewell Praying Wolf James. James is the head of the Lummi House of Tears Carvers, and has created a tradition out of carving and delivering totem poles to places that are in need of hope and healing.

In 2013, James launched a totem pole journey to build solidarity for Indigenous-led struggles against fossil fuels, including the struggle to protect Xwe’chieXen. James traveled 1,200 miles with his totem pole in 2013 — from the Powder River Basin to the Tsleil Waututh Nation across the Canadian border. In 2014, he launched another 6,000-mile totem pole journey in honor of revered tribal leader Billy Frank Jr, a Nisqually tribal member and hero of the fishing rights struggle. Frank passed away on May 5, 2014 — the same day he published his final piece condemning coal and oil trains.

These totem pole journeys have gained international attention as pilgrimages of hope, healing, decolonization, and Native resistance to the extractive industries.

At the end of August, James concluded his third regional totem pole journey against fossil fuels, carrying the banner of resistance to many tribes who are standing up as fossil fuel projects get knocked down. He held blessing ceremonies in Boardman and Portland where coal and propane projects were recently shot down, passed through the Lummi Nation and Longview where coal has yet to be defeated, and ended in the Northern Cheyenne Nation at Lame Deer, where the community has rallied in opposition to a mine whose devastation would reverberate from Montana, down the Columbia River, and up to Cherry Point.

“There are many of us who are joining, from the Lakota all the way to the West Coast, to the Lummi, south to the Apache, up to the Canadian tribes,” said Northern Cheyenne organizer Vanessa Braided Hair at a recent Tongue River Railroad hearing. “We’re gonna fight, and we’re not gonna stop.”