Leno Vela (center), 11, talks with JJ Gray (right), 5, at the Tulalip Boys and Girls Club.

By: Chris Winters, The Herald

TULALIP — Chuck Thacker was working as the principal of Quil Ceda and Tulalip Elementary School when he was approached about starting a Boys and Girls Club on the reservation of the Tulalip Tribes.

The tribes, Thacker and the Boys and Girls Clubs of Snohomish County all saw the need for a safe after-school program targeted at tribal youth. Thacker would contribute his leadership and experience working with kids, Boys and Girls Clubs of Snohomish County would provide the model, and the tribes would provide the startup money and location, as well as the kids.

The Tulalip Boys and Girls Club opened in 1996, the first club located on an Indian reservation in Washington and one of the first in the United States. The Tulalip Tribes continue to support the club financially to this day.

Charitable contributions by tribes have become more visible in an era in which some tribes have become financially successful in their business undertakings. But giving has always been a part of Native American culture, even before the 1988 Indian Gaming Regulatory Act created a national legal framework in which tribes could operate casinos on their reservations.

In Washington state, tribes such as the Tulalips who run casinos are required to donate a certain percentage of the proceeds to charity. But the tribe routinely exceeds that amount, and even tribes without significant income give back to their communities.

“This rule is not new to Indian Country, as it has now been formalized,” said Marilyn Sheldon, who oversees the Tulalip Charitable Fund.

“We’ve always been givers,” she said.

From left, Georgetta Reeves, 8; Ladainian Kicking-Woman, 6; Tristan Holmes, 11; and Isaiah Holmes, 6, hang out together in the gym at the Tulalip Boys and Girls Club.

The Tulalip Tribes

When Chuck Thacker sat down with Terry Freeman of the county Boys and Girls Clubs and Stan Jones, the former chairman of the Tulalip Tribes, they outlined a vision for the new club: It had to address needs of both the tribe and the surrounding community.

The goal was to create a safe after-school program that would accept both native and non-native kids; provide reading programs, other educational activities and sports activities; and remain open as many hours as possible. Most important, it would also provide a meal program.

Thacker recalled what Jones told him: “Feed our kids good, because a lot of them don’t get a good meal at home.”

The Tulalip Tribes backed up its support with financial assistance, and has provided the club with financial support every year since, allowing tribal kids to come to the club free of charge even while it has gradually expanded its services to include arts programs and a technology center.

The meal program now serves three meals a day to up to 250 youths.

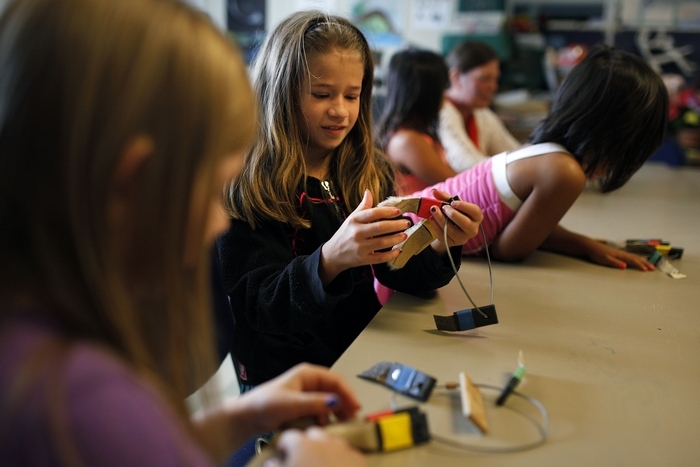

During a Pacific Science Center demonstration at the Tulalip Boys and Girls Club, Ashton Rude, 9, looks through animal furs and tries to identify them.

Thacker, who has directed the club since its inception, said “99 percent of them come in for activities, and they know the food’s going to be there.”

The Tulalip Boys and Girls Club is just one organization that’s been on the receiving end of the tribes’ charitable giving.

Since 1993, shortly after the Tulalip Tribes opened its first casino, charitable giving from the Tulalips has risen from $273,000 then to $6.9 million in 2013.

In the first half of 2014, the Tulalip Tribes has given more than 160 grants to nonprofit organizations, groups or programs both on and off the reservation. They include community groups, the Boys and Girls Clubs, arts organizations, environmental groups, educational programs and specific events, such as the tribe’s annual Spee-Bi-Dah celebration and parade and an emergency grant of $150,000 to the Cascade Valley Hospital Foundation and the American Red Cross to help victims of the Oso mudslide.

Marilyn Sheldon recalled that when she was growing up, her own mother and other tribal women in the ladies clubs would support their community with various fundraisers.

Tribal giving has been formalized since then, but it still draws on tradition. During the tribe’s annual Raising Hands gala, all attendees receive gifts as a way of honoring them. Children at the Montessori school also spread the table at the end of each year, Sheldon said, and gifts are traditionally given at funerals.

“That’s part of the healing of the family, to put all that love and energy into giving,” Sheldon said.

Since the Tulalip Resort Casino opened in 1992, a portion of all profits has been donated to charity.

Agreements between the tribe and Washington state set a minimum percentage of proceeds that must be given to charity, but the Tulalips now regularly exceed that baseline, said Martin Napeahi, the general manager of Quil Ceda Village, the Tulalip Tribes’ business and development arm.

In 1993, the Tulalips donated $273,000 to charitable causes. That rose to $6.9 million in 2013, the 20th year in which the Tulalip Charitable Fund has operated.

A committee weighs grant applications, but the members are all anonymous. Each serves for a two-year term and oversees one subsection of the grant requests — for example, natural resources, education, arts or social services.

Then, at the end of every quarter, the committee members switch assignments, so no one member evaluates the same subset of applications.

“That way it adds to the fairness of deciding who gets funding,” Sheldon said.

In the end, the tribes’ board of directors reviews the committee’s recommendation and decides which applications are funded and to what extent.

The fall Raising Hands gala is not just a celebratory event, but an opportunity to create more lasting bonds within the larger community.

Dignitaries and community leaders are invited to mix and mingle with the recipients of the tribes’ giving.

“The beauty of putting that together is you can put other groups together at the same table,” Sheldon said.

That, coupled with presentations honoring the work the various grant recipients do, turns the gala into a educational event as well, which creates connections among the disparate groups and may lead to future collaboration.

“We are doing the best we can to make a difference in our communities,” Sheldon said.

The Stillaguamish Tribe

The Stillaguamish Tribe of Indians has seen marked economic growth in the last decade.

When its Angel of the Winds Casino and Hotel opened in 2004, the tribe’s charitable giving evolved from a more casual undertaking to a formalized system.

“Prior to the casino we didn’t have a whole lot of money to give,” said Eric White, vice chairman of the Stillaguamish tribe.

“In fact, we were the ones out there asking for help,” he said.

Since instituting a formal giving program, the Stillaguamish convene a committee of tribal members and employees to evaluate grant requests.

The Stillaguamish gave $800,000 in donations during the tribe’s last fiscal year, which ended in October 2013, White said

So far this year, the Stillaguamish have donated about $1.9 million, with some of the larger recipients being relief agencies working in the aftermath of the mudslide. But recipients also have included community organizations, such as a $300,000 gift to local food banks that the tribe made before Christmas in response to an acute need.

“Basically our main mission would be to help the folks who are in need,” White said.

The Stillaguamish also make charitable donations to environmental organizations, animal rehabilitation services, recreation and health care, especially to the American Cancer Society, which White said the Stillaguamish has long supported.

The Sauk-Suiattle Tribe

Tucked up in the mountains near Darrington, the Sauk-Suiattle Indian Tribe doesn’t have a casino, other large business enterprises or even easy access to the sea for fishing.

The tribe derives its revenue from running the gas station in Darrington and a smoke shop on its reservation, and from leasing its gambling licenses to other tribes that do operate casinos.

Nonetheless, the Sauk-Suiattle tribe makes a point of contributing to the community.

“We do, on a yearly basis, take $30,000, sometimes $40,000 if we have extra, and make small grants to the city of Darrington,” said Ronda Metcalf, the tribe’s general manager.

Beneficiaries include the local senior center, the grange, the school and some programs through the pharmacy to help people pay for medication.

“We’re not obligated to do that, but it’s something the tribe felt would be a good way to build community with the city,” Metcalf said.

When the Oso mudslide cut Darrington off from the rest of the county, Sauk-Suiattle members came together and donated about $5,000 to families affected by the slide, and then came to the Darrington Community Center to lay out a blanket in a traditional form of fundraising, bringing in about $1,100 more on the spot.

A committee looks at requests and decides where the need is greatest. If there are many needy causes, the tribe tries to give out something to most of them, Metcalf said.

“Tribes have been doing that for a long time, it’s part of who they are,” Metcalf said.

Coming soon

This story is part of Snohomish County Gives, a special section highlighting the spirit of philanthropy in the county. Look for more stories on HeraldNet throughout the week and the full section in the print edition of The Herald on Sunday, Aug. 31.