By Cameron Langford, Courthouse News Service

(CN) – The Interior Department may be infringing on the religious freedom of Native Americans by limiting the right to possess eagle feathers to federally recognized tribes, the 5th Circuit ruled.

Understanding golden and bald eagles are essential for the religious practices of many American Indian tribes, Congress amended the Eagle Protection Act in 1962, adding an exception “for the religious practices of Indian tribes.”

Under the law, Native Americans could apply for a permit to take and possess eagles by attaching a certificate from the Bureau of Indian Affairs that verified them as Indian to their application.

Interior Secretary Bruce Babbitt narrowed the eligibility in 1999 to members of federally recognized Indian tribes.

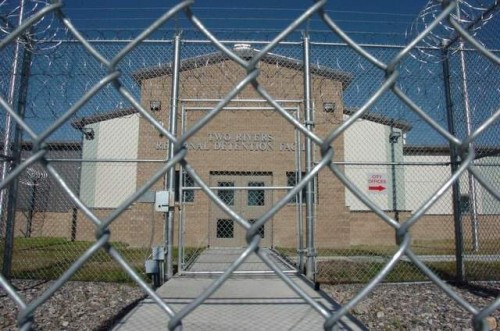

The National Eagle Repository in Colorado takes in dead eagle parts and distributes them to qualified permit applicants, with whole bird orders taking more than three years to fill, and loose feather requests taking about six months to turn around, court records show.

At a 2006 powwow a U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service agent found Robert Soto in possession of eagle feathers.

Soto told the agent he was a member of the Lipan Apache Tribe, and after the officer determined the tribe is not federally recognized, he met with Soto, who voluntarily gave up his eagle feathers in return for the government dropping its criminal case against him.

As pastor of the McAllen Grace Brethren Church and the Native American New Life Center in McAllen, Texas, Soto uses eagle feathers for his ministry’s religious ceremonies.

Soto “has been a feather dancer for 34 years and has won many awards for his Indian dancing and artwork at various powwows throughout the nation,” according to his self-published biography.

After the Interior Department denied Soto’s petition for the return of his feathers, he and 15 other plaintiffs sued, claiming the feather confiscation violated religious freedoms established by the First Amendment.

U.S. District Judge Ricardo Hinojosa sided with the feds and Soto appealed to the 5th Circuit in New Orleans.

Writing for a three-judge panel of the appellate court, Judge Catharina Haynes found the government had not carried its burden of showing its regulations are the least restrictive means of protecting what it claims are its compelling interests: protecting eagles and fulfilling its responsibility to federally recognized tribes.

Noting that the 1962 Amendment to the Eagle Protection Act “did not define ‘Indian Tribes,'” Haynes wrote on Wednesday, “We cannot definitively conclude that Congress intended to protect only federally recognized tribe members’ religious rights in this section.”

She added: “The Department has failed to present evidence at the summary judgment phase that an individual like Soto-whose sincerity is not in question and is of American Indian descent-would somehow cause harm to the relationship between federal tribes and the government if he were allowed access to eagle feathers, especially given congressional findings that the exception was born out of a religious concern.”(Emphasis in original.)

The law also grants the Interior Secretary authority to OK the taking of eagles or eagle parts for public museums, scientific groups, zoos, wildlife and agricultural protection.

Haynes took issue with the fact that the government did not bring up these various nonreligious exceptions to the law.

The feds additionally argued that removing barriers to possession would lead to a spike in poaching to supply a black market in eagles and eagle feathers.

But Haynes dismissed that as “mere speculation” by the federal agents who testified in the case.

“This case involves eagle feathers, rather than carcasses. It is not necessary for an eagle to die in order to obtain its feathers. Thus, speculation about poaching for carcasses is irrelevant to Soto’s request for return of feathers,” the 25-page ruling states.

In coming down on the side of religious freedom, the panel relied heavily on the Supreme Court’s recent Hobby Lobby ruling, which found that requiring some corporations to supply contraceptives to their employees against their religious objections violates the Religious Freedom of Restoration Act.

The panel reversed and remanded the case to Hinojosa and urged the government to prove the permitting system does not violate the RFRA.

In a one-page concurring opinion Judge Edith Jones said the ruling should be read to only apply to American Indians.

“Broadening the universe of ‘believers’ who seek eagle feathers might … seriously endanger the religious practices of real Native Americans,” she wrote.