Tag: BIA

BIA’s Funding Maze Hampers Tribal Self- Governance

A funding system that routes money through a bureaucratic maze with more than a dozen checkpoints before it arrives at its destination – tribal governments – is one of the obstacles Indian country faces in its quest for self-governance, the head of the Bureau of Indian Affairs said at the National Congress of American Indians annual meeting.

“Rube Goldberghimself couldn’t have come out with a more complicated system!” Assistant Secretary – Indian Affairs Kevin K. Washburn said, showing the amused audience a mind-boggling, arrow-marked illustration of how the funds flow. Washburn spoke to a full crowd packed into the General Assembly hall at the Hyatt Regency in Atlanta where the NCAI held its 71stannual Convention & Marketplace October 26-31.

The theme of this year’s NCAImeeting was “Tribal Governance for the Next Generation.” With that theme in mind. Brian Cladoosby, NCAI president and chair of the Swinomish Indian Tribal Community, encouraged NCAI member tribes “to remember the guidance of the generations that came before us while we move forward to continue to build a strong future to the generations to come.”

Washburn was among dozens of dignitaries – tribal leaders and federal government officials, including Interior Department Secretary Sally Jewell – who spoke at the convention. The convention’s theme prompted him to review what’s been done so far under the Obama administration to advance tribal governance and what remains to be done.

“We’re coming up on the fourth quarter,” Washburn said, referring to the last two years of the Obama administration that will end in 2016. “And it hasn’t been all victories, we’ve had some setbacks.” The top setback has been the failure so far to fix the Supreme Court’s devastating ruling in Carcieri v Salazar,which has hampered efforts to take land into trust for tribes.

“But what I’d like to do in the fourth quarter is really run up the score. We have to join together and work together to do that and NCAI is our best partner in doing that because it’s our best way of getting to tribes,” Washburn said.

Among recent victories Washburn cited the Violence Against Women Act, the Tribal Law and Order Actand the HEARTH Act.

Other achievements include the vastly improved consultation policy, copy3 million in technical assistance grants to 75 different tribes to move forward with energy projects and the settlement of over 80 lawsuits in addition to the Cobell settlement and several water rights cases. A major victory is the growing masses of land the BIA has taken into trust for tribes, despite the Carcieri ruling, Washburn said. “We’re restoring thousands of acres and literally hundreds of square miles to Indian country and that’s an important foundation for tribal governments for the next generation because land … is where a tribe’s sovereignty is the strongest.”

All of these advances have resulted in a little-known consequence that also advances tribal self-governance – the BIA’s reduced workforce from around 17,000 employees in 1981 to around 7,500 employees today. So where’d they all go? “They went to Indian country jobs,” said Washburn. “These jobs are being done better by tribal governments than they were by the federal government. They’re being done in Indian country and the people doing them are accountable to tribal governments.”

But in terms of moving tribal self-governance forward for the next generation, “we’ve got a lot of challenges,” Washburn said. Many of them have to do with how programs are funded. Several laws enacted over the years to encourage and improve tribal self-governance – the 1975 Indian Self Determination and Education Assistance Act; the 1988 tribal schools act; the Self-Government Demonstration Project Act, the Indian Employment, Training and Related Services Demonstration Act of 1992and others – have different funding requirements. And then there’s the money flow chart, which came to light when Washburn started asking why it took so long to get contract support funding out to the tribes.

“So what we have to some degree is disjointed programs and a lack of coordination between agencies sometimes,” Washburn said. “We must improve this!”

Washburn took ownership of the problem – “This is all on me,” he said – and informed the NCAI assembly that he is working with Deputy Assistant Secretary for Management Tommy Thompson to fix the problem. “We have got to get the money out to tribes quickly so that tribes can use that money when it’s needed. We’re trying!” he said. The audience gave him a standing round of applause.

Read more at http://indiancountrytodaymedianetwork.com/2014/11/14/bias-funding-maze-hampers-tribal-self-governance-157840

More forestry funding needed on Indian lands, tribal leader says

By Kate Prengama, Yakima Herald-Republic

Federal funding cuts pose dire consequence for the ability of tribes to manage their land and reduce wildfire risks, a Yakama Nation leader told a U.S. Senate hearing Wednesday in Washington, D.C.

Phil Rigdon, the director of the Yakamas’ natural resources program and president of the Intertribal Timber Council, told the Senate Committee on Indian Affairs that programs that once kept tribal forests healthy are now “running on fumes.”

“The consequences of chronic underfunding and understaffing are materializing,” Rigdon told the committee. “The situation is now reaching crisis proportions and it’s placing our forests in great peril.”

There are more than 18 million acres of tribal forest lands held in trust by the federal government, but the Bureau of Indian Affairs gets far less funding per acre for forest management and fire risk reduction than national forests.

Funding has fallen 24 percent since 2001, Rigdon said, and that can have dire consequences.

For example, last year when the Mile Marker 28 Fire broke out off U.S. Highway 97 on the Yakama reservation, only one heavy equipment operator and one tanker truck were able to respond immediately because that’s all the current federal budget supports, Rigdon said in an interview before the hearing.

“Back in the early 1990s, when I fought fire, we would have three or four heavy equipment operators,” he said. “Someone was always on duty. That’s the kind of thing that’s really changed.”

The Mile Marker 28 Fire eventually burned 20,000 acres of forest.

Rigdon noted that the dozens of tribes around the country that are represented by the Timber Council are proud of the work they do when resources are available.

“If you go to the Yakama reservation and see our forests, we’ve reduced disease and the risk of catastrophic fire. If we don’t continue to do that type of work — if we put it off to later — we’ll see the types of 100,000- or 200,000-acre fires you see other places,” Rigdon said.

Currently, there are 33 unfilled forestry positions at the BIA for the Yakama Nation, he added. That limits the program’s ability to hit harvest targets, which hurts the tribe economically and affects the health of the forest.

A 2013 report from the Indian Forest Management Assessment Team found that an additional $100 million in annual funding and 800 new employees are needed to maintain strong forestry programs on BIA land nationwide. The current budget is $154 million.

In addition to the concern over future funding, other members of the panel also discussed the different approaches to forest management by tribes and the Forest Service.

“We’ve done a good job maintaining a healthy forest on a shoestring budget, but the Forest Service is not maintaining its adjacent lands,” said Danny Breuninger Sr., the president of the Mescalero Apache Nation in New Mexico.

Committee member Sen. John McCain, R-Ariz., cited a 2011 Arizona fire as an example of how tribal efforts can succeed. In the wake of a 2002 fire, the White Mountain Apache conducted salvage logging and thinning work while the adjacent national forest did not. When fire hit the region again, federal forests were devastated, but the treated tribal forests stopped the fire’s spread.

Jonathan Brooks, forest manager for the White Mountain Apache, told McCain that lawsuits prevent the Forest Service from doing similar work.

“Active management gets environmental activists angry,” Brooks said. “But what’s more hurtful to the resources: logging, thinning and prescribed fire, or devastating fires?”

Rigdon said the Intertribal Timber Council would like to see increased abilities for tribes to work with neighboring national forests on management projects like thinning, which could support tribe-owned sawmills and reduce fire risks.

The Yakama Nation is working with the Forest Service on developing such a collaborative project, as part of a new program known as “anchor forests.” It’s a pilot program currently being used on a few reservations, and the panelists at the hearing supported expanding it to more regions.

Anchor forests are intended to balance the economic and ecological needs of a forest through a collaborative effort involving tribes, the BIA and local, state and federal agencies.

Carlisle Indian Industrial School Files Go Digital

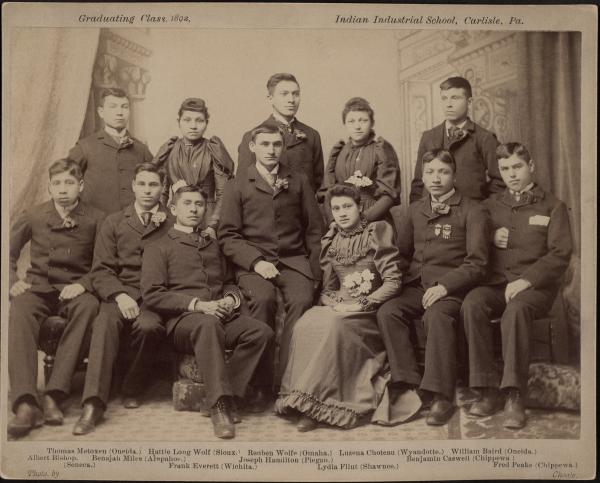

The caption reads: Graduating Class, 1892. Indian Industrial School, Carlisle, Pa. Thomas Metoxen (Oneida.) Hattie Long Wolf (Sioux.) Reuben Wolfe (Omaha.) Luzena Choteau (Wyandotte.) William Baird (Oneida.) Albert Bishop, (Seneca.) Benajah Miles (Arapahoe.) Joseph Hamilton (Piegan.) Benjamin Caswell (Chippewa.) Frank Everett (Wichita.) Lydia Flint (Shawnee.) Fred Peake (Chippewa.) Photographer: John N. Choate, Carlisle, PA

1/10/14 ICTMN.com

Want to know more about students who attended Carlisle Indian Industrial School? Now doing just that is far easier.

Stories of Sioux children like Elsie Robertson, or Pueblo children like Bruce Fisher can now be read online, as can parts of the lives of the many thousands of students who attended Carlisle between the years of 1879 and 1918.

Readers can find this information on the Carlisle Indian Industrial School Project page of Dickinson College of Carlisle, Pennsylvania. The college’s Community Studies Center (CSC) and its Archives and Special Collections Department put the project together in 2013 and since August of last year they have been sending teams of researchers to the National Archives to scan and digitize information relating to CIIS.

This week, project directors sent another team to the Archives to continue with the process. One of the directors, College Archivist Jim Gerencser, noted that they had already digitized 1,250 files, comprising about 11,000 pages of text.

“We think that within three years we should be able to capture all the information from the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) files,” Gerencser said.

He also said that they had been in contact with a group of CIIS descendants on Facebook and were hoping to inspire other people with connections to the school to come forward. The first page of the project’s website extends an invitation also.

“Desiring to add to the school’s history beyond the official documentation, we will seek partners among those institutions that hold additional records regarding the school, its many students, and its instructors. Subsequent phases of this project will develop the capability for user interactivity, so that individuals may contribute their own digitized photos, documents, oral histories, and other personal materials to the online collection. The website will also host teaching and learning materials utilizing the digitized content and database, and will support the addition of original scholarly and popular works based on the Carlisle Indian Industrial School Project resources.

BIA: Who’s your leader? C&A per cap checks on hold

December 4, 2013

By LENZY KREHBIEL-BURTON, Native Times

CONCHO, Okla. – Thanks to their tribes’ protracted leadership dispute, Cheyenne and Arapaho citizens will not be getting their December per capita payments on time.

According to a letter obtained by the Native Times on Nov. 26, the Bureau of Indian Affairs’ agency office in Concho denied a drawdown request by the Janice Prairie Chief-Boswell administration from two of the Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribes’ trust accounts. Among the withheld $3 million in lease funds are $1.6 million in oil and gas leases that provides an annual December per capita payment for tribal citizens.

“Regrettably, the Concho agency cannot honor your request for federal action as of this date because the agency does not know with certainty the identities of the validly seated governor, lieutenant governor and members of the legislature for the Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribes,” agency superintendent Betty Tippeconnie wrote in the letter, dated Nov. 21.

The tribe has been dealing with a constitutional crisis for almost three years, with both Prairie Chief-Boswell and Leslie Wandrie-Harjo each claiming to be the legitimate governor. The two women ran for office and were inaugurated together in January 2010, but their alliance dissolved within a year over a series of allegations. Since the women’s political partnership fell apart, each has formed her own government, claiming to be the legitimate authority over the Cheyenne and Arapaho tribes. Boswell and her supporters are working out of the tribal complex in Concho, while Wandrie-Harjo and her government is based out of nearby El Reno, Okla.

Federal law gives the Prairie Chief-Boswell administration 30 days to appeal the decision to the Southern Plains regional office in Anadarko or it will become final.

The Prairie Chief-Boswell administration did not respond to requests for comment. In a statement posted to her Facebook page, the other claimant governor urged her counterpart to negotiate a compromise in order to have the per capita payment funds released.

“All of us members need those per capita monies,” Wandrie-Harjo wrote. “We have suffered enough.

“Boswell needs to swallow her pride for the well-being of the members and meet w ith me and the BIA to get this per cap out or she needs to step down so the BIA and I can get the money out to the members.”

Meanwhile, the Supreme Court affiliated with the Prairie Chief-Boswell administration has not handed down a decision in either pending appeal of the tribes’ Oct. 8 primary election. The justices heard appeals from former governor and disqualified gubernatorial candidate Darrell Flyingman and tribal member and employee Joyce Woods on Nov. 15 and initially announced that a decision would be handed down within 10 days. No verdict had been announced by press time.

Revisiting racism

Ravalli comments leave tribal elders thinking of the past

Missoula Independent by Jessica Mayrer December 5, 2013

Confederated Salish and Kootenai tribal elder Tony Incashola Sr. says that despite experiencing racism from the time he was a child growing up in the 1950s on the Flathead Indian Reservation, he couldn’t help feeling surprised by a Ravalli County official’s portrayal of American Indians during a public meeting last month as drunken lawbreakers.

“I guess I shouldn’t be,” Incashola, 67, says. “I’ve lived with that all of my life … When I was a kid, it was like standing at a department store on the outside looking in. You see the non-Indian children having fun. You felt like an outsider, that you weren’t welcome, because you didn’t dress right and you had a different color.”

Incashola, who serves as director of the Salish-Pend d’Orielle Culture Committee, has dedicated much of his life to fostering an understanding of indigenous ways. Education breeds familiarity, he says. Familiarity helps break down the fear that breeds racism. Efforts such as his are paying off. Incashola says that racism is less apparent than when he was young. That makes the Nov. 20 meeting in Ravalli County all the more troubling.

The meeting involved a discussion between CSKT delegates and the Ravalli County Board of Commissioners about how best to care for a historic Bitterroot Valley property known as Medicine Tree that the Salish have considered sacred for hundreds of years. CSKT wants to transfer the property from tribal ownership into federal trust with the Bureau of Indian Affairs. CSKT representatives stated that the 58-acre parcel is central to Salish creation stories, ones that detail how “Coyote,” a being imbued by the creator with special powers, made the land “safe for humans yet to come,” Incashola says.

When explaining the importance of such a transfer, the CSKT say that the Medicine Tree parcel provides a connection to indigenous history—a link that helps preserve a strong sense of tribal identity. The CSKT add that the transaction will help grow their land base and, therefore, give them a more powerful voice when negotiating their rights and responsibilities with government agencies.

CSKT attorney Teresa Wall-McDonald told the Independent that placing land into trust helps the tribes gain back losses accrued when the federal government opened the Flathead Reservation to non-native homesteaders in 1910. Between 2009 and August 2013 alone, the CSKT placed approximately 81,000 acres into trust.

“Part of the process of restoring our homeland includes restoring the land,” Wall-McDonald says. “It is part of rebuilding our homeland, what I call nation building.”

The Ravalli County Commission, however, has steadily opposed the CSKT’s request. Among the commissioners’ stated concerns is the loss of roughly $800 in property taxes that would result from the transfer. They also worry about the potential impacts of having a pocket of sovereign land set aside within their county, and why the tribes would want to work with the federal government rather than local. At the Nov. 20 meeting, they asked specifically if the tribes intended to erect a casino atop the parcel.

Later during the same meeting, Ravalli County Planning Board Chair Jan Wisniewski warned commissioners of the CSKT’s request, saying that American Indians have a history of using trust lands as a refuge to “get drunk and try and run back into the reservation so they don’t get caught,” according to meeting minutes.

“The county cannot go into that sovereign nation to apprehend the drunken Indians,” he said. “So the jails are full of Indians (sic) which cost us tax dollars. One jail in particular (Havre?) had a count of 58.”

In response to Wisniewski’s testimony and the behavior of the Ravalli County officials, Bitterrooter Pam Small posted an online petition demanding that the commission apologize for the county’s “cultural insensitivity and ignorance” that garnered nearly 500 signatures.

Such criticism helped persuade the commissioners on Nov. 27 to issue an apology to the tribes. Roughly 20 Bitterroot residents attended the meeting, with many of them verbally lashing out at the commissioners, characterizing the county’s overall treatment of the CSKT as “paternalistic” and akin to “an inquisition.”

“The whole tone of this meeting was confrontational,” former Ravalli County attorney George Corn said. “They were grilled by your attorneys … At best it was denigrating. At worst, it implied racism.”

In response to the onslaught, county commissioners say that the Nov. 20 discussion was taken out of context—that they were only attempting to evaluate all possible outcomes that could result from the transfer. “It was in no way condescending or adversarial,” Commissioner Jeff Burrows said last week, before the commission voted to hand-deliver an apology to the tribes.

Wisniewski’s legal advisor, Robert C. Myers, echoes the commissioners when maintaining that his client’s statements were taken out of context. “We don’t know yet fully what was actually said,” he says. “People hear what they think they hear.”

For Incashola, the issue comes back to education and respect. For instance, he says the thought of the tribes placing a casino on Medicine Tree is preposterous and reflects a misunderstanding of the importance the CSKT place on preserving their culture.

“I think the county commissioners don’t understand,” Incashola says.

The whole back and forth leaves him weary.

“I get so tired of trying to defend my identity, to try to defend my values,” he says. “I feel that what happened in Hamilton is just plain ignorant.”

Incashola says his elders, who faced the worst kind of racism, taught him that there are more good people in the world than bad. He takes some comfort in that thought. In light of what transpired in Ravalli County, however, Incashola isn’t confident that racism will ever completely disappear.

Limited Services Provided by Indian Affairs During Government Shutdown

Source: Indian Country Today Media Network

With the government shutdown now in its second day and around 800,000 non-essential government workers being furloughed, some offices working directly with Indian country will have limited services.

RELATED: Government Shutdown Frustrates Tribal Leaders

The Department of the Interior – Office of the Assistant Secretary-Indian Affairs, Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA), and Bureau of Indian Education (BIE) will provide limited services to tribes, students and individuals during the shutdown of the federal government. Of the total 8,143 employees, a total of 2,860 will be furloughed.

The BIA that provides direct services to 566 federally recognized tribes that include contracts, grants and compacts will continue functions that are necessary to protect life and property. These services include law enforcement and operations of detention centers; social services to protect children and adults; irrigation and power – delivery of water and power; firefighting and response to emergency situations according to a BIA press release.

As for the BIE, school operations are forwarded funded meaning operations should carry on as normal during the shutdown. BIE funded schools will remain open and staffed; transportation and maintenance of schools will continue. Other schools that will remain open are tribally-contracted schools that are also forward funded. Education services are provided by BIE to approximately 41,000 Native students through 183 schools and dormitories and providing funding 31 colleges, universities and post-secondary school according to the release.

Additional information on Indian Affairs’ contingency plan for operations during the government shutdown can be found at: www.doi.gov/shutdown.

Read more at http://indiancountrytodaymedianetwork.com/2013/10/02/limited-services-provided-indian-affairs-during-government-shutdown-151558

With Federal Shutdown Looming, Interior Releases Contingency Plan for BIA

Levi Rickert, Native News Network

WASHINGTON – For the first time in 17 years, a federal shutdown is realistic at 12:01 am est Tuesday, October 1.

Late Saturday night, the Republican-controlled US House passed a measure that would fund the federal government at its current level for one year with the stipulation, the Affordable Care Act – most commonly known as Obamacare – would not be part of the federal budget.

This measure is unacceptable to President Barack Obama and the Democratic Party-led United States Senate.

With the US Senate not reconvening until this afternoon, it is looking more and more likely a federal government shutdown will occur at midnight tonight.

What does this mean to Indian country?

The federal shutdown will impact some services in Indian country. The breakdown is broken down into two categories as essential and non-essential services. Essential services include law enforcement and social services to protect children and adults.

“The impact of a Federal government shutdown is elusive to most folks as we, as citizens, generally take government services for granted. The impact in both the short term and long term to Tribes, however, will be devastating. In 1995, the impact was to delay federal checks, impose furlough work days for federal employees, shut down federal tourist and National Park services, and ultimately the cost of both closing down and reopening Federal services at a whopping $1.4 billion ($1.7 billion today with a one percent annual inflationary adjustment),”

commented Aaron Payment, chairman of the Sault Ste. Marie Tribe of Chippewa Indians, based in Sault Ste. Marie, Michigan, to the Native News Network Sunday morning.

“In some cases, the Sault Tribe subsidizes a large portion of the Federal government’s treaty obligations for “health, education, and social welfare”. One hundred percent of the Sault Tribe’s net gaming revenues are already pledged to pick up the Federal government’s annual shortfall. For some programs – not all – we will be able to rely on Tribal support or casino dollars for a brief period. However, for those programs not subsidized by Tribal Support funds, we will have to consider furloughs. In some cases, federal funds have already been received such that we can operate for a few days during a shut down. However, if the shutdown lasts more than a week, we may need to shut programs down. In this event, we will first try to minimize the impact on services and second on jobs,”

Chairman Payment continued.

“Obviously we are watching the possible shutdown by the federal government. We are trying to balance what we can do at home and we are reviewing what possible services would be impacted by the shutdown,”

commented Erny Zah, director of communications from Navajo Nation President Shelly’s office on Sunday evening.

“Our Council just passed our budget, so we are attempting to see how a shutdown will coincide with our new budget. Our goal is to keep all government services unhindered and uninterrupted as possible.”

The Bureau of Indian Affairs, BIA, is part of the federal government under the US Department of the Interior. Late Friday, the Interior Department released the following contingency plan fact sheet:

Bureau of Indian Affairs

Contingency Plan Fact Sheet

With a potential shutdown on October 1, 2013, the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) will be required to administratively furlough all employees unless they are covered in an Excepted or Exempted positions. The BIA will also discontinue most of its services to tribes which will impact most programs and activities.

Services and programs that will remain operational.

- Law enforcement and operation of detention centers.

- Social Services to protect children and adults.

- Irrigation and Power – delivery of water and power.

- Firefighting and response to emergency situations.

Services and programs that would be ceased.

- Management and protection of trust assets such as lease compliance and real estate transactions.

- Federal oversight on environmental assessments, archeological clearances, and endangered species compliance.

- Management of oil and gas leasing and compliance.

- Timber Harvest and other Natural Resource Management operations.

- Tribal government related activities.

- Payment of financial assistance to needy individuals, and to vendors providing foster care and residential care for children and adults.

- Disbursement of tribal funds for tribal operations including responding to tribal government requests.

Feds hear about Indian tribe recognition proposal

Federal officials heard testimony Thursday in Solvang on proposed changes to the process for Native American tribes to get recognized, a procedure speakers described as expensive, lengthy and burdensome.

July 26, 2013 LompocRecord.com Julian J. Ramos/jramos@lompocrecord.comIn June, the Department of the Interior (DOI) released a draft of potential changes to its Part 83 process for acknowledging certain groups as American Indian tribes granted a government-to-government relationship with the United States.

At the moment, the U.S. has 566 federally recognized tribes, of which 17 have been recognized through Part 83. California has 109 federally recognized Indian tribes with between 70 and 80 seeking federal recognition.

The draft proposal, the subject of two sessions Thursday at Hotel Corque, is meant to give tribes and the public an early opportunity to provide input on potential changes to the Part 83 process.

Proposed revisions are intended to improve transparency, timeliness, efficiency, flexibility and integrity in the acknowledgment process, according to the DOI.

However, critics of the proposed rules are calling them the “Patchak patch,” a reference to Supreme Court decision last year in favor of David Patchak, a Michigan man who challenged the way the government takes land into trust for tribes.

They say the proposed rules are meant to drastically limit the uncertainties created by the Patchak decision by adding administrative barriers for potential litigants and rushing fee-to-trust acquisitions, which removes land from local jurisdiction and makes it part of an Indian reservation, under tribal authority.

Larry Roberts, deputy assistant secretary for Indian Affairs, said the presentation during the afternoon public meeting was the same delivered during the morning tribal consultation session.

The public session Thursday afternoon drew between 60 and 70 attendees, including Solvang Mayor Jim Richardson, in the ballroom of the hotel, which is owned by the Santa Ynez Band of Chumash Indians.

Many of the speakers represented California tribes seeking recognition, a process they described as cumbersome, costly and very time consuming, or as Mona Olivas Tucker, tribal chairwoman of the Yak Tityu Tityu Northern Chumash in San Luis Obispo County, put it, something she doesn’t expect to be completed in her lifetime.

Valentin Lopez, tribal chairman of the Amah Mutsun Tribal Band of Coastanoan/Ohlone Indians in the San Juan Bautista area, said the acknowledgment process is getting more and more difficult, is too lengthy, should be moved out of the hands of the DOI Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) and the burden of proof for recognition should revert to the BIA from tribes.

Michael Cordero, tribal chairman of the Coastal Band of the Chumash Nation, said criteria changes could make it easier to be recognized and tribes, such as his, could benefit from the acknowledgment.

A “Letter of Intent,” which begins the acknowledgment petition process, has been submitted for the tribe, he said.

During a break, Cordero said the session had been helpful in clarifying some issues on the process and requirements.

Across San Luis Obispo, Santa Barbara and Ventura counties, the Coastal Band of the Chumash Nation has about 2,500 enrolled members, Cordero said.

Under the proposal, reviews of a petitioner’s community and political authority — criteria for acknowledgment — would “begin with the year 1934 to align with the government’s negation of allotment and assimilation policies and eliminate the requirement that an external entity identify the group as Indian since 1900,” according to the DOI.

No More Slots attorney Jim Marino asked why 1934 is being used in the criteria. He represents several groups against more Indian gaming and land acquisition through the fee-to-trust process, which removes land from local jurisdiction and makes it part of an Indian reservation under tribal authority.

The 1934 Indian Reorganization Act represented a “dramatic” shift in federal policy toward self determination for tribes and the use of that year as a benchmark is meant to reflect that change, Roberts said.

To block attempts to annex property into the Santa Ynez Reservation, opponents of the Santa Ynez Band of Chumash Indians have questioned whether it’s legally a tribal government and thus able to take land into trust via the fee-to-trust process.

The battle centers on Chumash efforts to annex almost 7 acres they own across Highway 246 from the tribe’s Santa Ynez casino.

Members of Preservation of Los Olivos (POLO) and Preservation of Santa Ynez (POSY) have presented documentation to the Bureau of Indian Affairs the groups believe prove the Chumash were not under federal jurisdiction in 1934, and do not qualify to take any land into trust.

By contrast, the Chumash tribe logo and flag says “Federally Recognized Tribe since 1901.”

Due to POLO’s continuing litigation, the group has been advised not to comment on the proposed rule change, POLO president Kathy Cleary said.

Other plans by the Chumash to annex property into the reservation, notably 1,400 acres they own about 2 miles east of the casino and an additional 5.8 acres in the casino area along Highway 246, have also been met with opposition.

Sam Cohen, legal and government affairs specialist for the Chumash, said the proposal is not applicable to the local tribe.

“The Department of the Interior has started to initiate the process of reviewing revisions to the federal acknowledgment regulations for Native American tribes that hope to be federally recognized,” he said in a statement. “Since the Santa Ynez Band of Chumash Indians was federally recognized in 1901, the revisions don’t apply to the Santa Ynez Chumash tribe.”

Transcripts from both sessions will be available at www.bia.gov, officials said.

The discussion draft is available for review at www.bia.gov/whoweare/as-ia/consultation.

Interior officials will accept written comments on the draft until Aug. 16 by email to consultation@bia.gov or by mail to Elizabeth Appel, Office of Regulatory Affairs & Collaborative Action, U.S. Department of the Interior, 1849 C Street, NW, MS 4141, Washington, DC 20240.