By S.E. Ruckman, Native Times Special Contributor

OKLAHOMA CITY – Despite living in a state where Medicaid was not expanded, Oklahoma’s 38 federally recognized tribes have found a way to state tribal liaison, Sally Carter – and she has found her way to them. In this newly created position, Carter is quick to tell you that she considers Oklahoma to have 39 tribes because even though the Euchee are not federally recognized, they are state recognized. Breathlessly, she says she is learning fast.

“I still count them,” she said.

Carter carries Euchee concerns on health matters back to the state capital as part of a new stance where the health decision makers seek to repair a long and tenuous relationship between historical archetypes. When the Affordable Care Act (ACA) was passed in 2010, a series of listening sessions between Oklahoma and the tribes occurred at six different tribal jurisdictions across the state to talk about the federal health overhaul. Replete with opening ceremonies and songs, the state was figuratively stretching its hand toward its Native inhabitants.

From these beginnings, Carter takes the message back to the capital that the tribes want to be at the decision-making table with state leaders, including the newly re-elected Republican governor, Mary Fallin.

Carter said the tribes don’t just want to be told about important developments, they want to help shape the direction the state will take on things such as the implementation of the ACA and how to reduce health disparities like high smoking and diabetes rates in their nations.

To date, 1,638 American Indians in Oklahoma have enrolled for federal health insurance through ACA while 13,061 have enrolled nationally, according to a U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) report. When compared to the 9.1 million estimated Obamacare enrollees, American Indians number roughly 1 percent of all Americans who now have health insurance who had none before.

But that thing that makes Oklahoma’s Indian Country so different—that thing that separates it from other U.S. states with tribes – is that it has no official Indian reservations. A federal land allotment experiment from the 1900s crisscrossed the state’s territory into a veritable smorgasbord of jurisdictions – federal, tribal, municipal, state.

Carter is working on how to stimulate enrollment among Oklahoma tribes.

If the government wants to reach the American Indians here, it’s best to go to each tribe, Carter said. That was a go-to move state health officials embraced as they discussed ACA with the tribes. The things Carter found surprised her although she is an Oklahoma resident and had lived near various tribal jurisdictions for years.

“They are the only (minority) group that has to show their race,” she said, her voice lilting. “I mean, no other group has to do that. They have to prove it with an enrollment card of some kind.”

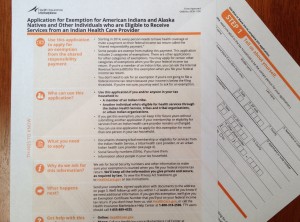

Official American Indian citizenship is important because the ACA has special provisions that allow Indians to “opt out” of having to enroll in federal health insurance, if they choose. But Indians need to fill out form OMB No. 0938-1190 that officially removes them, officials said. Not doing so will mean an eventual penalty.

“(ACA) is very complex and not one of us would say that we know it all,” Carter said. So the state took the best of what they knew after weeks of training on the health plan to several tribal jurisdictions. When all sides met, Carter said she was schooled. American Indians have strong opinions about the state/ federal government encroaching on their personal privacy and tribal sovereignty with this new federal health insurance.

Because Oklahoma chose not to expand Medicaid, enrolling American Indians in ACA takes a certain degree of cultural finesse and dogged persistence, Carter said. In other tribally populated states, like North Dakota, the move to expand Medicaid fills in where ACA may not be a strong priority, said Sen. Heidi Heitkamp, D-ND. The emphasis is reducing uninsured numbers, she said.

“The State of North Dakota expanded Medicaid, which has helped uninsured, low-income individuals and families, including many Native Americans throughout the state, get access to affordable health care,” Heitkamp said. “ Medicaid expansion is giving families opportunities they didn’t have before to afford to see a doctor regularly and get access to needed medications, while reducing costs for everyone – those with health coverage and those without.”

The Oklahoma tribal liaison added that even while enrollment curiosity abounded, many did not qualify for ACA because they did not file income tax returns. American Indians can enroll in ACA at any time – not just during enrollment periods, but their tax filings allow them also to file the exemption – if they chose to forgo coverage.

American Indians have a higher unemployment rate than other groups–peaking in 2013, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics Current Population survey. Indian unemployment rates averaged 11.3 percent compared to 9.1 percent of the mainstream during that time. High unemployment rates among Indians tend to keep more Indians ineligible for ACA enrollment, Carter said.

What has also dampened Oklahoma’s outreach has been a distrustful relationship between the state and tribes—this makes it harder for federal initiatives to come through the front door, said Terry Cline, Oklahoma’s commissioner of health. He points to the good faith of the tribal/state meetings.

“I considered the listening sessions a good start,” he said. An official summary on the sessions reported 193 attendees at the six sessions, several of which Cline attended.

“We held those sessions to have open dialogue,” he said. “What you hear from one tribe might be different from another tribe says.”

As for ACA and tribes, a tribe’s type of relationship with the federal government, either Self-Governance or direct service, dictated outreach approaches because that’s how health dollars are administered by tribes in states, especially in Oklahoma, officials said.

Tribes that operate under provisions of the Indian Self Determination Act might outreach on ACA directly to members in their own tribally run health systems and tribes that are direct service entities may forgo outreach to their local Indian Health Service (IHS) service facility. In both regions, IHS and tribal facilities can accept ACA insurance from patients and lessen the amount of contract (out-of-IHS system) health dollars it spends, officials said.

“Tribes have a lot of interest in ACA,” Carter said. “Tribal leaders and the health department can inspire and direct tribal members to enroll.”

Both of the tribal-to-federal relationships are considered when the state of Oklahoma contacts tribes, and the state tends to follow the federal approach, Carter said. Putting on different hats to deal with different tribes is prudent.

“Tribes need to see people they know and that they can trust who know about American Indian provisions,” she said. “I believe in face-to-face interactions. States usually contact them (tribes) with emails or letters, but a relationship needs to be worked on and allowed to develop.”

Cline said no special state appropriations exist to outreach to tribes for ACA enrollment in Oklahoma but he’s optimistic that other types of federal grants to reduce health disparities will help. The health commissioner said he knows Oklahoma has room for ACA Native growth through grants.

The HHS report points out that Oklahoma has the highest density of Indians among Federally Facilitated Marketplace (FFM) states with 3.5 percent of the population followed by Wyoming, with 3.1 percent. Wyoming’s total Native ACA enrollment stands at 309, the report shows.

At this point, Oklahoma seems to lead the state in the number of Natives it has enrolled, just exceeding figures for California. But as enrollment rolls on, officials expect more American Indians to register. Indian Country (the term used to characterize where a federal-tribal relationship exists) extends beyond Oklahoma.

Other states with significant Native populations include Arizona, California, New Mexico, South Dakota and North Dakota. ACA data gathering for Native numbers is in its infancy, organizers said. They say the goal is to pool their information from various regions (via Indian advocacy agencies) to get a more precise picture of Native ACA enrollment. Due to their smaller population numbers, American Indian statistics are often overlooked, officials said.

Other mainstream entities who track the progress are unclear about just how many have actually signed up for ACA. Michelle McEvoy, vice-president of survey, research and evaluation for the Commonwealth Fund, said that no Native specific information has been garnered by her group.

“Latinos currently represent about 17 percent of the U.S. population, so they have a greater probability of being sampled than American Indians who represent about 1.2 percent of the U.S. population,” she said.

Likewise, the non-profit Enroll America, relies on Native ACA enrollment numbers from federal sources, wrote Jessica McCarron, deputy press secretary, by e-mail.

“We do work with partners at the local level to reach different communities, like Native American groups in certain parts of the country,” McCarron stated. “We work with a few partners who have made outreach to tribal communities a high priority.”

Meanwhile, Carter is optimistic about ACA enrollment and reaching American Indians in Oklahoma.

“(ACA) is bigger than all of us,” she said. “We can’t do this alone; it only happens when the state extends its hands across the table and says we need to do this for all the people.”

– This story was funded by the University of Southern California’s (USC) Annenberg School of Journalism as one project undertaken by the 2014 class of California Endowment Health Journalism Fellows. S.E. Ruckman is writing a three-part series on the Affordable Care Act (ACA) in Indian country. In addition to mainstream viewpoints, American Indian health advocates and American Indian enrollees are visited to gauge the national health plan’s implementation in Native populations. Fellows’ projects can be found at www.reportingonhealth.org.

NATIVE AMERICAN ACA ENROLLEES STATE ENROLLMENT TOTALS

*Wyoming: 309

*New Mexico: 566

*Oklahoma: 1,635

+California: 1,401

*Arizona: 514

*North Dakota: 82

*South Dakota: 271

TOTAL: 13,061

Sources: (March 2014) *HHS Summary Report; +California Department of Health Care Services