By Carmen George, The Fresno Bee, June 27, 2014

Editor’s note: Information in the third and fourth paragraphs has been revised to clarify details.

Two little American Indian girls hid motionless in a cave, covered in brush as soldiers passed through Yosemite Valley.

Older members of their Yosemite tribe made a quick escape up a steep, rocky canyon, and the girls were temporarily left behind, told not to make a sound.

This was the mid-1800s during the era when armed soldiers marched into Yosemite Valley not as explorers, but as men out for blood. At the first, they burned villages and stores of acorns, meat and mushrooms. Later on, they patrolled, yet the fear of them remained.

One of those concealed girls, Louisa Tom, lived to be more than 100 years old. She never got over those early images. Into old age, when uniformed park rangers entered her village in Yosemite Valley, she would run and hide behind her cabin, recalls great-granddaughter-in-law Julia Parker, 86, who has worked in the Yosemite Indian museum for 54 years.

For many American Indians, the inspiration for Yosemite National Park did not start with flowery prose from John Muir or a romantic vision of Galen Clark in the Mariposa Grove of giant sequoias as its “first guardian.” It began with murder and destruction.

TIMELINE: Slide and click through Yosemite’s history

For them, the story of Yosemite since the mid-1800s is tragedy and tears, yet resilient Native Americans have survived and still live in this mountain paradise.

“We’re still here, living in the Yosemite Valley,” Parker says. “So you can’t keep a good people down.”

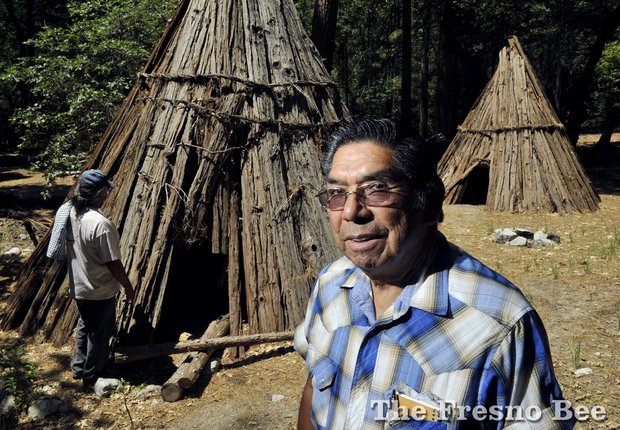

On Monday, many descendants of these “first people” will attend a ceremony in the Mariposa Grove to celebrate the 150th anniversary of the Yosemite Grant Act — precursor to national parks. Les James, 79, a tribal elder active in Yosemite’s native community, will say a blessing, but he won’t be celebrating.

“The changes, the destruction, that’s what I don’t like about it. You destroyed something that we preserved for thousands of years. In 150 years, you’ve ruined it.”

For most of his life in the Yosemite area, James has worked to return cultural activities. He also had a 31-year career in Yosemite, starting in 1959, making trail and warning signs. Over his lifetime, there have been 24 park superintendents.

Helen Coats, 87, is the great-granddaughter of that little girl hiding in the cave. Coats, born in Yosemite Valley, lived in its last native village, destroyed by the Park Service by 1969.

She now lives down Highway 140 in the Mariposa area. She sees “busloads after busloads” of tourists pass by every day. Sometimes, it makes her sad.

“They are just trampling my home to death.”

A dark chapter

To understand the viewpoint of Yosemite’s first people, go back to March 27, 1851 — about 13 years before the Yosemite Grant Act was signed.

On that spring day, during a hunt for Indians who were rumored to be living in a mountain stronghold, the first publicized “discovery” of Yosemite happened.

The natives living in this ethereal place were called the Ahwahneechees, and they already were competing with the Gold Rush to survive. In 1849, there were 100,000 miners swarming the foothills, wrote Margaret Sanborn in “Yosemite: Its Discovery, its Wonders and its People.”

SPECIAL REPORT: Yosemite celebrates 150th anniversary

After an attack on a trading post on the Fresno River near Coarsegold owned by pioneer James Savage, 23 natives were killed by a volunteer company. The group, led by Savage, became the Mariposa Battalion. Federal Indian commissioners — eager to make treaties — told Savage to not “shed blood unnecessarily.”

The battalion discovered Yosemite searching for Indians. During early military expeditions, some natives were shot and killed or hung from oak trees in Yosemite Valley.

Lafayette Bunnell, a battalion member, recorded Chief Tenaya’s reaction finding his son shot in the back trying to escape.

“Upon his entrance into the camp of volunteers, the first object that met his gaze was the dead body of his son. Not a word did he speak, but the workings of his soul were frightfully manifested in the deep and silent gloom that overspread his countenance.”

Later, Tenaya tried to escape by plunging into the river, but was spotted. “Kill me, sir captain! Yes, kill me, as you killed my son; as you would kill my people, if they should come to you! … Yes, sir American, you can tell your warriors to kill the old chief … you have killed the child of my heart …”

The assault would splinter the Ahwahneechee tribe — some fleeing over the Sierra, others rounded up in the foothills.

Their descendents live on. Today, at least seven organized Native American groups have traditional ties to Yosemite, according to Laura Kirn, Yosemite’s cultural resources program manager.

But the pain of their past lives on, too.

Jack Forbes, a former American Indian studies professor at the University of California at Davis, writes about the previous era in “Native Americans of California and Nevada.” He suggests few chapters in U.S. history are more brutal and callous than the conquering of California Indians.

He writes: “It serves to indict not a group of cruel leaders, or a few squads of rough soldiers, but, in effect, an entire people; for the conquest of the Native Californian was above all else a popular, mass enterprise.”

Weight of difference

Coats was born in Yosemite Valley in May 1927.

As a child, she loved to roam and pound berries atop boulders in her village, where women pounded acorns. Sometimes she would dress in buckskin and beads to visit grandmother Lucy Telles weaving baskets for tourists.

It was a good childhood, Coats says, but she couldn’t help notice being treated differently than white children. She recalls that at her Yosemite school, she drew pictures or made dolls, and then was met with an encouraging “Oh, that’s so nice” from the teacher.

“They didn’t try to teach us,” Coats says of schooling for natives. “I guess they thought we wouldn’t make a good pupil maybe for reading and writing.”

Coats was born in the “old Indian village,” tents by current-day Yosemite Village, which now includes a large gift shop, market and pizzeria. In the early 1930s she was moved to a new Indian village near Camp 4, more than a mile away with 17 small cabins. Kirn says the move was to provide more privacy and better housing.

But Coats sees it differently. “The old village, we were too visible. People could really see us there, the way we lived in tents, you know. We were the poor people of Yosemite.”

The Indian cabins lacked what other park houses had, like private bathrooms, warm water, bigger windows and second stories, Coats says.

Feeling the power

Walking through a Yosemite Valley meadow, Bill Tucker, 75, points to plants his Miwuk and Paiute people ate. Many also were used for healing.

Coats recalls a doctor who said her great-grandma would die overnight, but family members placed cooked wild onion on her chest. “Next morning, she was fine.”

In the meadow, Les James looks up at the cliffs. “I can feel that power.”

“Everything is living on Mother Earth,” he says, and even the rocks have stories. Like El Capitan, the world’s largest granite monolith. The name “captain” was thought fitting for this massive stone, but according to native legend, it was named after one of the smallest creatures: An inchworm.

This comes from a tale about the rock’s creation, much like the “Tortoise and the Hare.” The story goes that two children sleeping on a stone awoke to find it grown. All kinds of animals tried to scale its sheer face to rescue them. Then came a little worm.

“This little guy, he’s the underdog,” James says, “and they laugh at him about what he’s going to do, inch his way up and save the kids.” But the worm succeeds. “Even if you’re a little guy, don’t worry, you’ll be famous someday,” James says with a smile.

El Capitan is not El Capitan. It’s the “Measuring-Worm Stone.”

Many visitors today miss Yosemite’s wonder, says Lois Martin, 70, who grew up in the native village and is chairwoman of the Southern Sierra Miwuk Nation. “It’s so commercialized.”

But many hold to a hope that in Yosemite, humanity might still connect to indigenous roots shared by all. The late David Brower, the Sierra Club’s first executive director, once said people need places to be reminded that “civilization is only a thin veneer over the deep evolutionary flow of things that built him.”

Meadow manhole

Walking through green grass in Yosemite Valley, James and Tucker come upon concrete. Tucker, a retired park plumber, says it’s part of an old sewer line — a manhole in the meadow.

It gets him thinking about his 30-year career in the park. Memories of burst sewer lines and the wastewater treatment ponds in Tuolumne Meadows, in the high country, give him chills.

Many of Yosemite’s American Indians also worry about species management: the killing of “non-native” fish and plants considered invasive in Yosemite Valley, such as blackberry bushes, which have been sprayed with pesticides. Over five years, 40 acres have been treated with a weed killer, Kirn says. “We believe that if an animal does digest it, it’s about as safe as a chemical can be.”

Yosemite’s first people weren’t trying to preserve an untouched wilderness, but they understood nature and lived light on the land. They had the advantage of thousands of years of experience.

The park often has glossed over the native role in the evolution of Yosemite’s meadows, says University of California at Davis lecturer M. Kat Anderson in “Tending the Wild: Native American Knowledge and the Management of California’s Natural Resources.” For example, the natives regularly set fires to help oaks produce more acorn.

“They told us how many mushrooms to pick, how many fish to catch,” James says of the Park Service. “They think we didn’t know that. We taught them that.”

Park officials over the years gradually have come to recognize the value of native stewardship.

Some of the natives, however, question how the Park Service manages things.

In the Camp 4 parking lot, James and Tucker spot a new paved trail leading toward Yosemite Falls. They don’t understand how the park is touting removing pavement in the Mariposa Grove as more is laid down in Yosemite Valley.

Yosemite National Park spokesman Scott Gediman said the native community has many legitimate concerns, but the park gets almost 4 million visitors a year, and managing the place is “always a balancing act.”

But, he said, “our highest calling and our No. 1 priority is always preserving the natural environment of Yosemite, and the less development the better.”

Coats says she understands why the Park Service does some construction: “The park is kind of like Disneyland. There’s so many people in there. I can kind of relate to them fencing off things because in the old days they didn’t have to do that.”

What, then, is the value of the indigenous perspective in this new, much more populated and modern Yosemite? Maybe it boils down to this, says James: “For thousands of years, we were here before them. That’s because we lived by nature’s law. If you don’t live by nature’s law, you are not going to survive. That’s really the bottom line.”

Losing home

Archaeological evidence shows people in Yosemite Valley about 7,000 years ago, Kirn says. In areas bordering the park, evidence dates back 9,500 years. That’s about the time people perfected hunting woolly mammoths.

That residency in Yosemite ended for many in the 1960s when descendants of those original people, like Coats, were told to leave.

A bed of pine needles covers the place where Coats’ cabin once stood, but the 87-year-old still can find her way to this spot, following the boulders.

This was the park’s last native village. In the 1960s it was decided only natives with full-time work could live in Yosemite. As many lost seasonal employment, like Coats, who did tourists’ laundry, their homes were destroyed by the Park Service.

A few families with full-time work were moved elsewhere. Parker says, “When they separated us, I couldn’t go out there and sing a song, I’d be disturbing the neighbors.”

Today, the community is rebuilding its village. Included in the 1980 general management plan, it will be used for ceremonies and gatherings.

The project hit a rough patch a few years ago. Roundhouse beams were deemed unsafe and the park put a stop to construction. Yosemite’s native community needed to follow building codes.

“They’ve got codes for churches, bowling alleys, everything else, but not for roundhouses,” James says. “The white man is trying to tell us how to build a roundhouse when he doesn’t know how to build it himself.”

This month, a compromise was reached. An American Indian engineer will be hired.

Kirn is eager to see the roundhouse built. “It’s a place in which they can continue to be present in the park and work in partnership with all of us to maintain the sacred nature of Yosemite.”

Preserving culture in national parks is taking on growing importance, says William Tweed, retired chief park naturalist at Sequoia and Kings Canyon National Parks, in “Uncertain Path: A Search for the Future of National Parks.”

“In this new century, where nothing natural or wild seems beyond the threatening reach of humankind, the cultural values associated with national parks may ultimately be their most important feature.”

The return of culture

In the last half century, spiritual camps were started — ceremonies for healing and honoring all life, and an annual spiritual walk, tracing ancestors’ steps over the Sierra.

The walk is important to Tucker, as it’s a time of learning. Like above Mono Lake, when children see the sunrise for the first time, glittering on distant water. And watching kids turn into young adults, helping elders carry backpacks and pitching tents before thundershowers.

There also are sunrises over Tenaya Lake, known by the first people as “Lake of Shining Rocks” for granite domes rolling above the water. Tucker thinks of those mornings. “Pretty soon that good ol’ fog comes up out of that lake, and just kind of dances out there.”

Tucker also helps with bear dances, ceremonies held three times a year in Yosemite to honor the bear as it awakes from winter, forages in the summer and returns to hibernation with the onset of new snows.

The natives share a special connection with the bear, says Jay Johnson, 82, a Miwuk and Paiute instrumental in the native community and who worked in park forestry for 41 years.

Johnson’s aunt once spoke to a bear lying in the road after a line of angry motorists failed to clear the path. “Uncle, you’re going to have to move,” she told the bear in her native language. “We have to go down after groceries, after food.” The bear moved.

Johnson has worked to get the Miwuk tribe federally recognized. But an application, submitted in the early 1980s, remains before the Bureau of Indian Affairs. Many suspect their homeland being in a national park has played a role in the delay.

“As long as they keep pushing us back, we’re like a lost tribe,” says Coats, who is Miwuk and Paiute.

Finding a voice

After basket weaver Lucy Telles died, Parker, her granddaughter-in-law, was asked by the Park Service to fill her place in the Indian museum.

But Parker said she “wasn’t scholarly,” couldn’t make baskets and wasn’t from Yosemite. The orphaned Pomo and Coastal Miwok woman moved to the park at age 17 and a year later married a native to Yosemite.

Yet she gave it a shot and learned to weave when she was about 20. One day, she heard things said of natives that weren’t correct, “so I thought I better answer the question and put my basket down. And now my grandchildren say, ‘You can’t stop talking, Grandma!’ ”

Today, four generations of women in her family weave baskets and share native stories. Parker’s baskets have been given to the queen of England, king of Norway and the Smithsonian Institution.

In earlier years, Parker also worked in the gift shop of glamorous Ahwahnee Hotel in Yosemite Valley. “I was probably one of the first Indian ladies to work in the gift shop. When I worked in the gift shop, they had me stand in the corner like a wooden Indian. They didn’t think I could handle any of the cash register.” One day she filled in for a cashier but was told she couldn’t handle more than $10.

Eventually, she was made manager of a new Indian shop. Parker’s request that five American Indians work there was granted.

At 86, she still is in the museum. Earlier this month, Parker was awarded the Barry Hance Memorial Award, an honor presented annually to a park employee for strong work ethic, good character and love for Yosemite. Over 54 years, “sometimes I think, is it worth all this? Having people ask you, ‘Are you a real Indian?’ ”

But then, “If I wasn’t here, who would be here?”

Parker makes a point to connect with children when they visit. They like her stories, baskets and games. She likes helping them think about grandmas. She wants them to know a grandma’s stories are important.

Coats feels the same. “Ask your grandparents. They are not going to tell you nothing unless you say, ‘What happened in your day?’ They are going to think you’re not interested. … The way you learn our history is through us. You don’t read this in books. You have to read it through the elders.”

Making peace

Walking from Yosemite’s last native village, Coats thinks about what happened to her ancestors, the killings and the displacement.

“They came and took what they wanted, as they did all over America. … There’s always going to be a little anger inside.”

But, she adds, “What good is it to get angry? You can’t do anything with anger. Some things you have to accept — but you never forget, you pass on your history.

“The more people become aware of some of the background of the Native Americans, the more I think they try to understand. I think understanding can bring people closer together, to maybe work together, instead of being prejudiced — and that goes both ways.”