401(K)2013 / cc via flickr

By Mark Trahant, Alaska Dispatch News

These days “new” money is hard to find. That’s the kind of money that’s added to a budget, money that allows programs to expand, try out new ideas, and look for ways to make life better. Most government budgets are doing the opposite: Shrinking. Calling on program managers and clients alike to do more with less.

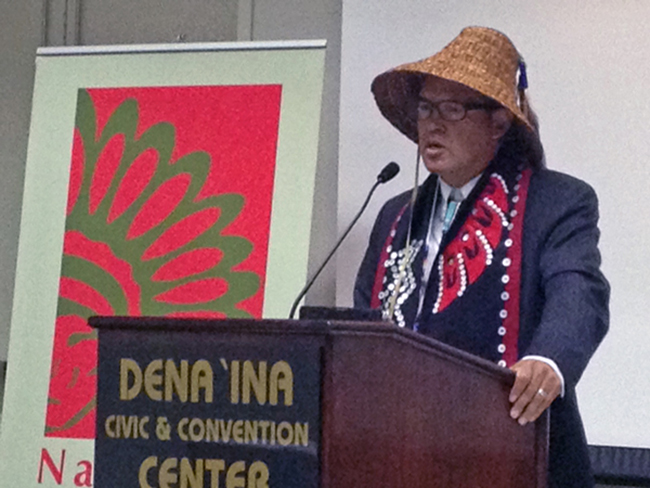

That’s why the news from Alaska last week is so exciting: Alaska’s new governor announced the expansion of Medicaid and this will significantly boost money for the Alaska Native medical system. Indeed, the significance of this announcement to the Indian health system was clear when Gov. Bill Walker and Department of Health and Social Services Commissioner Valerie Davidson made the announcement at the Alaska Native Medical Center on July 16. The governor took this action using executive authority because the Alaska Legislature had failed to even vote on legislation to accept Medicaid.

The governor says Medicaid expansion would reduce state spending by $6.6 million in the first year, and save over $100 million in state general funds in the first six years. “Every day that we fail to act, Alaska loses out on $400,000,” the governor said. “With a nearly $3 billion budget deficit, it would be foolish for us to pass up that kind of boost to Alaska’s economy.”

“We know Gov. Walker has worked tirelessly to expand Medicaid since he came into office on December first,” Davidson said at the news conference. It was one of the campaign promises made by the independent governor. “He included it in the budget. He introduced a bill both in the House and in the Senate side. It was a subject of both special sessions. And, it’s the right thing do do for Alaska.”

The expansion of Medicaid is one of key components of the Affordable Care Act. It’s critical a tool for the Indian Health System because it opens up a revenue channel for clinics and hospitals to bill Medicaid, a third-party insurance, for services. That boosts budgets at the local level, in a political climate where Congress is unlikely to spend more money on Indian health. How big a number? More than a million American Indians and Alaska Natives are now insured by Medicaid. The Kaiser Family Foundation estimated in 2013 that Indian health facilities collected $943 million in third-party payments.

“By far the largest third-party payer is Medicaid, which accounts for $683 million or 70 percent of total third-party revenues, and 13 percent of total IHS program funding for FY2013,” Kaiser reported. Nearly 150,000 Alaska Natives and American Indians receive health services across the state from tribal and nonprofit health organizations funded by the Indian Health Service. By law IHS-funded clinics must seek third-party billing from patients, such as Medicaid, the Veterans Administration or private, employer-based health insurance.

Medicaid is an odd program for Indian country. Most of us understand the IHS to be the government’s fulfillment of its treaty obligations. However the agency has never been fully funded. Medicaid, however, is an unlimited check. If a person is eligible, then the money is there. Yet states, not tribes nor the federal government, determine the rules for Medicaid. And many Republican states have been determined to fight the Affordable Care Act, or “Obamacare,” at every turn, and that means refusing to accept Medicaid expansion (the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in 2012 that states could turn it down).

Alaska’s decision means the number of states rejecting Medicaid is continuing to shrink. Most recently, Montana agreed to expand Medicaid in April. The states with large American Indian and Alaska Native populations that have not expanded Medicaid include Oklahoma, South Dakota, Wisconsin, North Carolina, Maine, Wyoming, and Idaho. Utah is the next state considering an expansion.

The Affordable Care Act continues to evolve — and improve. But more important, steps that states are taking to expand Medicaid are adding real dollars to the Indian health system.

Mark Trahant is an independent journalist and a member of The Shoshone-Bannock Tribes. He served two terms as the Atwood Chair of Journalism at the University of Alaska Anchorage. For updated posts, download the free Trahant Reports smartphone and tablet app.

The views expressed here are the writer’s own and are not necessarily endorsed by Alaska Dispatch News, which welcomes a broad range of viewpoints. To submit a piece for consideration, emailcommentary(at)alaskadispatch.com.