By Randy Ellis, The Oklahoman

An Oklahoma couple has filed a federal lawsuit challenging the constitutionality of portions of the Oklahoma Indian Child Welfare Act.

The couple specifically objects to provisions of the Oklahoma act that permit tribes to intervene in private, voluntary adoption cases involving Indian children.

Under the Oklahoma law, tribes are allowed to intervene — even when both birth parents oppose tribal intervention and have agreed on who they want as adoptive parents for their child.

“It’s nobody’s business who is involved in the adoption and they shouldn’t have to give anybody any notice and run the risk of having all their personal information exposed to other people,” said Tulsa attorney Paul Swain, who represents the couple in the lawsuit filed Wednesday in Tulsa federal court.

The couple contends that people of Indian descent, just like non-Indians, should have a right to privacy in voluntary adoption cases and that the state law giving tribes the authority to intervene violates their constitutional rights to due process and equal protection under the law.

Oklahoma Attorney General Scott Pruitt and Cherokee Nation Attorney General Todd Hembree are listed as defendants in the lawsuit because of their official positions.

Chrissi Nimmo, assistant attorney general for the Cherokee Nation, said the tribe believes it is important for tribes to have a voice in adoptions of Indian children and it plans to vigorously defend the law.

The Cherokee Nation is a government and has an interest in what happens to its citizens, just like the State of Oklahoma has an interest in what happens to its residents, she said.

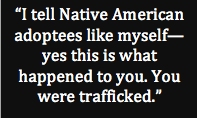

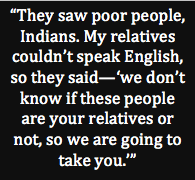

“In addition, we have a history that led to the Indian Child Welfare Act of children being removed from their tribes and their families,” Nimmo said. “Even in voluntary placements, there’s a long history where young mothers were coerced by adoption agencies to place their children for adoption because there was an attitude that a child would be much better off with a middle class or upper middle class home than to be raised by a young Indian mother.”

Nimmo said the Cherokee Nation likes to be notified early when a tribal member wants to put a child up for adoption so that the tribe can work with the birth parents to identify prospective Indian adoptive parents agreeable to all, before other arrangements have been made.

The Oklahoma Supreme Court has previously upheld the constitutionality of the Oklahoma act, she said.

A spokesman for Pruitt said he had not yet seen the lawsuit.

The lawsuit uses fictitious names to identify both the birth parents and prospective adoptive parents to protect their identities. The birth couple, who are both 18 and unmarried, are referred to as Jane and John Doe, while the prospective adoptive parents are referred to as Richard and Mary Roe.

“After discussing the matter with their counsel, Jane and John Doe became incensed that the Cherokee Nation would have any right to interfere with the adoption plan … which they had agonized over for many months,” the lawsuit states.

Although the birth mother is enrolled in the Cherokee Nation, the birth father is not and neither birth parent grew up following tribal traditions or participating in tribal events, the lawsuits says.

“They do not know anything about the Cherokee culture and heritage and, at this point, they have no interest in learning about those subjects,” the lawsuit states.

The prospective adoptive father is enrolled in the Cherokee Nation, but the prospective adoptive mother is not enrolled in an Indian tribe, according to the lawsuit.

“Jane and John Doe are also adamant that they do not want the Cherokee Nation put on notice regarding Baby Doe’s adoption,” the lawsuit says. “This notice will result in word spreading in the tribal offices of their adoption plan in violation of their privacy rights and if the tribe seeks out alternate placements, then others in the tribal community will learn of their adoption plan and John and Jane Doe feel that the decisions that they have made for their child are confidential and are not the proper subject for discussions among tribal members.

“This will result in embarrassment and immense pressure to deviate from what Jane and John Doe have determined to be the best decision for Baby Doe.”

The lawsuit states that the initial couple that the birth parents selected to serve as adoptive parents “made the tearful decision to withdraw from the adoption because they did not want to experience the emotional turmoil of litigating an adoption case.”

That couple was not of Indian descent, but had an adoption profile that impressed the birth parents, who spent months building a relationship with them, the lawsuit says.

The birth parents subsequently selected another couple as prospective adoptive parents, and that couple joined them in filing the federal lawsuit.

The Oklahoma Indian Child Welfare Act goes beyond the federal Indian Child Welfare Act by granting tribes the right to intervene in voluntary adoption cases, the lawsuit says.

The federal act gives tribes the right to intervene in cases where there has been an involuntary termination of parental rights, which can happen for a number of reasons including abandonment, neglect, abuse or failure to provide financial support for a child.

Under state law, when an Indian child is put up for adoption — absent good cause to take other action — preference is to be given to a member of the child’s extended family, other members of the Indian child’s tribe or other Indian families.

Both the state and federal Indian Child Welfare Acts were written to halt a trend of huge numbers of American Indian children being taken from their parents and placed with white foster or adoptive parents because of cultural differences rather than actual abuse or neglect.

The federal and state Indian Child Welfare Acts both have come under attack recently in a number of court cases.

In May, the Oklahoma Court of Civil Appeals ruled that contrary to new Bureau of Indian Affairs guidelines, a judge can deviate from child placement preference contained in the federal Indian Child Welfare Act when such action is in the best interest of a child.

In July, the Goldwater Institute filed a class-action lawsuit in Phoenix contending the federal Indian Child Welfare Act is unconstitutional because it doesn’t give Indian children the same right that other children have to be placed in homes based on their best interests, without regard to their race. That case is pending.

The Oklahoma and federal Indian Child Welfare Acts frequently come into play in Oklahoma foster child placement and adoption cases. About 30 percent of the children in state care have American Indian ancestry, according to a spokeswoman for the Oklahoma Department of Human Services.

Less than a year after being placed in the care of his grandmother, Leland was taken to the Indian Health Services Hospital for a minor burn on his foot. After Leland was treated, he was taken to another hospital in Gallup, New Mexico, where the Bureau of Indian Affairs decided to investigate.

Less than a year after being placed in the care of his grandmother, Leland was taken to the Indian Health Services Hospital for a minor burn on his foot. After Leland was treated, he was taken to another hospital in Gallup, New Mexico, where the Bureau of Indian Affairs decided to investigate.