By Shaelyn Hood, Tulalip News

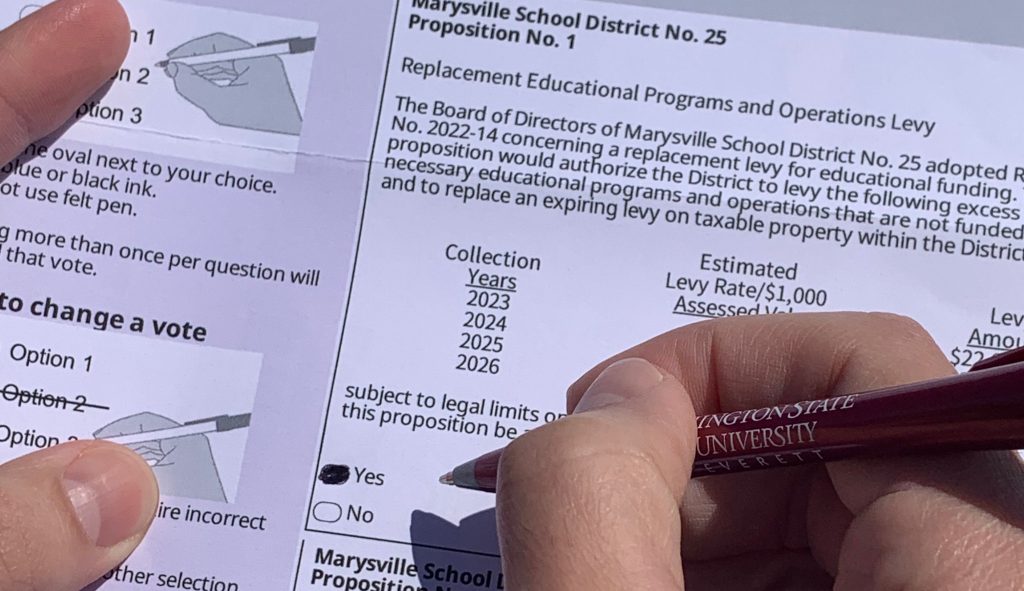

On February 23, the Marysville School District (MSD) introduced two levies to the community. These typically take place when a school district is needing more funds and property taxes are instilled as a way to subjugate them. The introduced levies from MSD are the Education, Programs & Operations levy, and the Technology & Capital Projects levy.

Though the relationship between Tulalip Tribal members and MSD has wavered for many years, the levies are a way to join forces and make a better environment for students.

Executive Director of Education, Jessica Bustad spoke about the troublesome relationship, “for years, people within our community have not been satisfied with the District. There’s a lot of pain and trauma around experiences that have happened in public schools. There is a lot of healing that needs to be done, and we have to work through that and make sure that the school district is held accountable. But at the same time, we also have to be supporting our students, and the levies can help do that.”

The Education, Programs & Operations levy is designated to help support smaller class sizes, making it easier for children to get one-on-one attention. It also helps establish programs for students with disabilities. It provides student transportation with more bus stops and shorter bus rides. In addition, it supports the Early Learning Center for pre-k kids, and many of the arts, music, athletics, and various extra-curricular activities.

The Technology & Capital Projects levy is designated to help integrate better technology for students, provide system administrators to oversee the school systems, aid curriculum software and licensing, and provide 24/7 WIFI access across all buildings.

With the district serving more than 1,200 Native American/Alaskan Native students, with the local Native population primarily consisting of Tulalip tribal citizens, the Tulalip Education Division is a driving force of support.

“This directly impacts our kids and tribal support is crucial. If we can get a high voter turnout from the Tulalip community, then we can impact and sway the vote, just by us exercising our right. We have to do what’s right on behalf of our students and the community,” Jessica said.

At a community meeting held in the Administration Building, Interim Superintendent Chris Pearson also addressed the unsteady relationship and how MSD is trying to bridge a new path with staff. He discussed the evolution of four new board members, including Superintendent Zachary Robbins and Executive Director of Finance David Cram. Chris went on to say, “there’s been significant change in our upper level positions, and we want to rewrite our story and improve the work that we do.”

One common misperception of levies is how they affect the overall revenue that the schools receive, and why they are a necessity when public schools already receive state and federal funding. According to last year’s revenue chart produced by the District, the federal revenue only makes up for about 14% of the schools funding, state revenue makes up about 68%, Local Non-Tax makes up 1%, misc. other makes up 3%, and still 14% of the school’s revenue comes from must needed property taxes.

Currently, there is still a healthy number of projects that need to be taken care of to maintain the different schools’ infrastructures. Knowing this, the District is trying to improvise and find ways to get funding elsewhere. Eventually, within the next five years, Chris said they do see themselves having to apply for a bond and completely rebuilding the older schools. Understanding this, they are willing to put some projects to the side in order to keep property taxes lower.

Unfortunately, as Chris also pointed out, enrollment in MSD has declined in recent years. This hurts the schools because they receive a certain amount of money per enrolled child, and as a result of this, some of the state funding has declined as well. This limits the District on how they allocate funds for the schools’ maintenance, building infrastructures, and overall budgeting. Making this a pivotal moment for the schools when establishing funds for the fall.

Anyone who is registered to vote in the state of Washington and lives within Snohomish county is able to vote yes to pass the levies. Ballots were mailed out on April 7th, and all ballots must be administered into one of the drop box locations by April 26th. The closest drop box to tribal members is located in the Tulalip Youth Center parking lot.

If you or anyone else would like more information about the levies and how beneficial they could be to our tribal students, please reach out to the Tulalip Education Division at 360-716-4909. And don’t forget to vote!