Tulalip Tribes Stickgame Tournament

Board chair delivers State of the Tribes

Source: Marysville Globe

TULALIP — Tulalip Tribal Board Chair Mel Sheldon Jr. will give this year’s State of the Tulalip Tribes address during the Greater Marysville Tulalip Chamber of Commerce Business Before Hours monthly breakfast starting at 7 a.m. on Friday, April 26.

The presentation will take place in the Canoes Cabaret of the Tulalip Resort Casino, located at 10200 Quil Ceda Blvd.

The cost is $23 per person for those who preregister, or $28.00 at the door. Reservations made and not honored will be billed.

For other reservation information, contact the Chamber by phone at 360-659-7700 or via email at admin@marysvilletulalipchamber.com.

Tribe closes Lake Quinault to non-tribal fishing

Source: KOMO 4 News

TAHOLAH, Wash. (AP) – The Quinault Indian Nation is closing Lake Quinault on the Olympic Peninsula to non-tribal fishing until further notice.

President Fawn Sharp said Tuesday the emergency measure is aimed at protecting water quality in the tribe-owned lake.

She said tribal leaders are concerned leaky septic tanks owned by non-tribal residents in the area may have caused untreated sewage to get into the lake. The tribe has detected pollution in some areas of the lake and plans to conduct more water quality tests.

Sharp said the tribe plans to monitor any fish caught by tribal members. She said they are also worried about reports of illegal fishing by non-tribal members and docks being built illegally on the lake.

The lake is located on the southwestern edge of Olympic National Park.

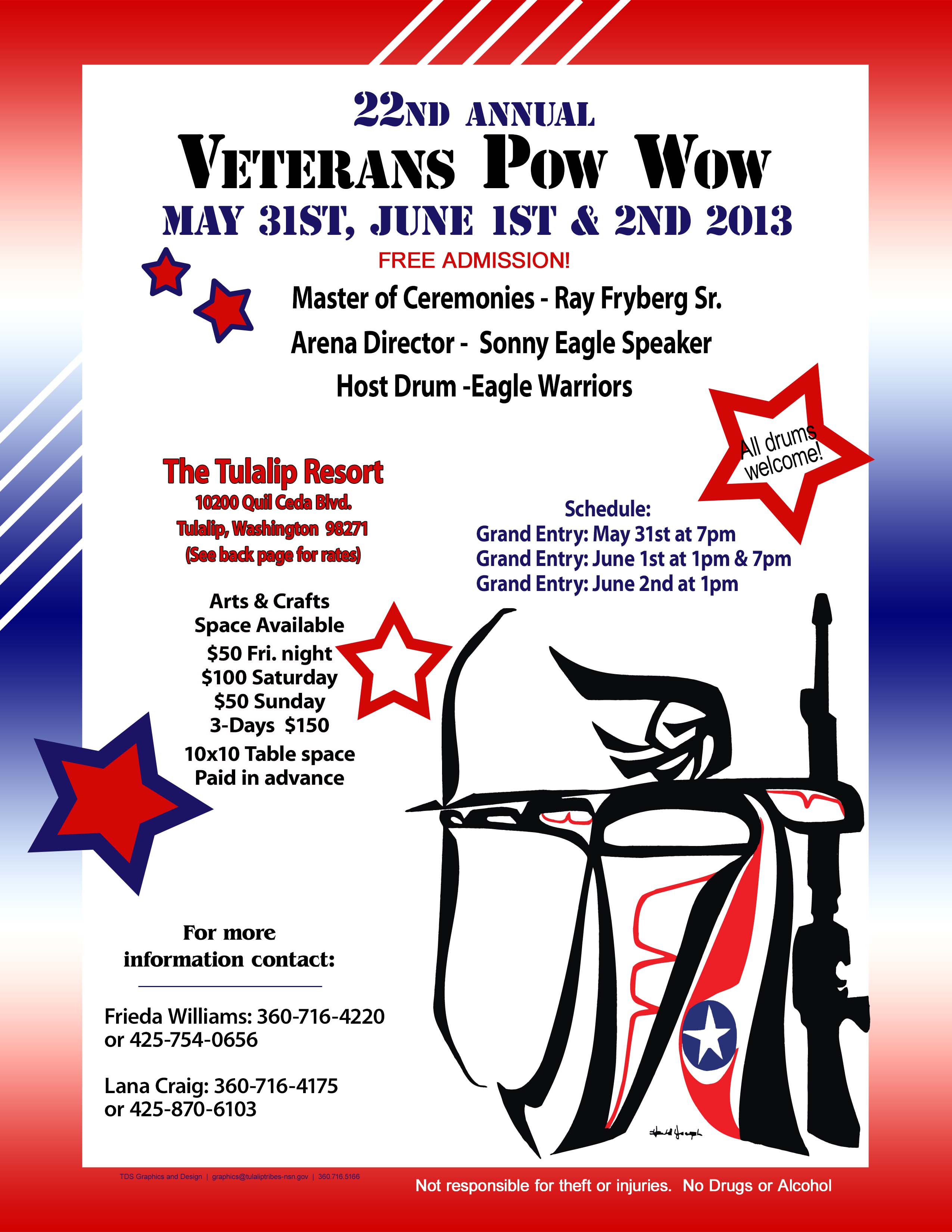

22nd Annual Veterans Pow Wow

Eight Great Healthy Reasons to Put On a Smile

Delegation from Lummi Nation Visit Pacific Luther University

Pacific Luther University, Chris Knutzen Hall 7:00pm, April 22nd, 2013

Source: Pacific Lutheran University

As part of Earth Day celebrations at Pacific Luther University during the week of April 21st, a delegation of representatives of the Lummi Native American Nation is being invited by PLU student club G.R.E.A.N. (Grass Roots Environmental Action Now) to visit Pacific Luther University on Monday April 22nd, 2013 and speak to the university as well as the wider community about a fight they are in the midst of waging.

Directly to the North of the Lummi Indian reservation, which is located near Bellingham, Washington, lays a forested and rocky shoreline known as Cherry Point, or Xwe’ chi’ eXen to the Lummi. It is at this site near the Straits of Georgia in the Salish Sea that SSA Marine, an international shipping company, has proposed building what would be the nation’s largest coal export terminal. The forest would be convereted to mountains of coal and the waters off of Cherry Point would be converted to mooring space for up to three of the largest sized ships in the world.

The problem lies in the fact that the Lummi consider Cherry Point and the ajoining waters a sacred site. The Lummi point to burials grounds, ancient villages and fishing sites at Cherry Point as reasons for opposing the export terminal; the terminal would undermine the Lummi’s right to economic prosperity, cultural dignity and spiritual well-being. With SSA Marine spending tens-of-thousands of dollars a day on PR, the Lummi have been overwhelmed, unable to get their message to as many people as the corporations. Thus, this event seeks to give a forum to the Lummi, one where they can share their story, in their own words.

Please join us for an evening of listening, conversation, and solidarity.

Suquamish Tribe donates fry for release in Carkeek Park

Source: Northwest Indian Fisheries Commission

In its 10th year of a successful partnership, the Suquamish Tribe has donated 50,000 chum salmon fry to the Carkeek Watershed Community Action Project, supporting the effort to teach the public about salmon and why it’s important to keep streams clean.

“A few years ago, we released 70,000 fry and 164 came back last year, which is a good return for us,” said Bill Hagen, the volunteer coordinator for the community group.

Suquamish natural resources technician Ben Purser takes a dip net of chum salmon fry from the tribe’s Grovers Creek hatchery near Indianola. The fry were transferred to Carkeek Park’s Piper Creek in Seattle. More photos of the transfer can be found on NWIFC’s Flickr page.

“We appreciate volunteers all over Puget Sound who are excited about the salmon life cycle and teaching others about it,” said Jay Zischke, the tribe’s marine fish program manager. “These types of programs are key to helping stress the importance of clean water, for both fish and people.”

The fish were donated in March and kept in a large swimming pool at the end of a trail on Piper’s Creek until released in April. Volunteers, from retirees to entire families, feed the fish three times a day until they are released.

The creek and trail are popular with school groups learning environmental science and the salmon-watching public, especially in the fall.

About 700 people came up this trail last year, Hagen said, so it gets a lot of traffic and is a good place for both kids and adults to learn about salmon.

“This is enjoyable for everyone who comes up here and if it weren’t for the tribe, we wouldn’t have it,” Hagen said.

Indian Affairs, Adoption, and Race: The Baby Veronica case comes to Washington

A little girl is at the heart of a big case at the Supreme Court next week, a racially-tinged fight over Native American rights and state custody laws.

By Andrew Cohen

Apr 12 2013, 10:52 AM ET in The Atlantic

The United States Supreme Court next Tuesday hears argument in a head-spinning case that blends the rank bigotry of the nation’s past with the glib sophistry of the country’s present. The case is about a little girl and a Nation, a family and a People. The question at the center of it has been asked (and answered) over and over again on this blessed continent for the past 400 years: Is the law of the land going to preclude or permit yet another attempt to take something precious away from an Indian?

The case is styled Adoptive Couple v. Baby Girl, but everyone knows it as the “Baby Veronica” case. The “baby” is a little girl, now three-and-a-half years old, born of the fleeting union of an American Indian man named Dusten Brown and a Hispanic woman named Christina Maldonado. Before Veronica was born, her mother arranged for her to be adopted without telling the baby’s father. When, months after the baby’s birth, the father found out about the adoption, he exercised his rights under federal law to block the adoption and gain custody. The two state courts which have reviewed the case have both sided with him.

The adoptive family, the couple who joyfully took Baby Veronica home from the hospital to South Carolina following her birth, claim that Brown waived his rights to custody under state law. The father, who now lives with the little girl in Oklahoma, claims that his conducts falls perfectly into the safe harbor of the Indian Child Welfare Act (ICWA) of 1978, a federal law designed to protect Indian families from “abusive child welfare practices that resulted in the separation of large numbers of Indian children from their families and tribes through adoption or foster case placement.”

So there is an intensely personal component to the case. And there is the larger picture, the political calculus, that seems to animate every high-profile Supreme Court case. This is yet another case about federalism — about states’ rights — some experts have told the Court. And Paul Clement, the conservative lawyer representing the child’s guardian in the case, has made an extraordinary argument designed to undercut federal oversight over Indian affairs: These statutes, he argues, are unconstitutional because they are based upon racial classifications that violate the equal protection rights of non-Indians.

Some of the elements of the case, sadly, harken back to the bad old days of dark stereotypes about Indians. The adoptive couple, who’ve relentlessly argued their case in the court of public opinion by appearing on television with the likes of Anderson Cooper and Dr. Phil, have been widely portrayed as the innocent victims of the story. Meanwhile, Baby Veronica’s father has been largely portrayed as little more than a shifty, good-for-nothing drifter. The truth lies somewhere in the middle — and the fact is that Baby Veronica’s story is precisely the sort of story Congress had in mind when it passed the ICWA.

Which is why it was a surprise to many when the justices in Washington agreed to hear the case. The Supreme Court of South Carolina, where the adoptive couple lives and where Baby Veronica was located at the time of the lawsuit, ruled that the federal law trumped state law and gave custody of the child back to her biological father. So did the justices take the case to reaffirm the primacy of Congressional authority over the lives of Native Americans? Did they take the case to strengthen the federal law? Or did they take the case to force Baby Veronica’s father to give her back to the white couple who thought they had successfully adopted her?

Some Facts

Like most cases that come before the Supreme Court, the “Baby Veronica” case has many more villains in it than heroes. Neither of the little girl’s biological parents respected each other enough to do right by their legal or moral obligations to one another. The father did not want to pay child support. The mother did not tell the father that she intended to place the baby up for adoption. The adoptive couple filed for adoption three days after Baby Veronica was born but didn’t give her father official notice of the proceedings for four months — that is, until just a few days before Brown, a U.S. Army soldier, deployed to Iraq.

There was a lot more of this sort of shadiness surrounding the adoption. Baby Veronica’s mother knew that the father was a member of the Cherokee Nation. She evidently told both the adoption agency and the adoptive couple that the father was Cherokee, but also acted in ways designed to conceal the situation from Indian officials (and, for that matter, from the little girl’s father). Before the baby’s birth, for example, there was an unsuccessful attempt to notify tribal officials, but Brown’s first name was misspelled on the notice, and his birth date on the form was, as the South Carolina Supreme Court later found, “misrepresented.”

Transporting the baby from Oklahoma, where she was born, to South Carolina, where the adoptive couple lived, required the consent of Oklahoma officials. On the state form, one option for identification was labeled “Caucasian/Native-American-Indian/Hispanic.” The word “Hispanic” was circled (although it is unclear who circled it). Had the Cherokee Nation known about the baby’s heritage, an Indian official later testified at the four-day hearing in the case, it would have objected and prevented the child from leaving the state. In short, everyone knew that there were “Native American” interests in the adoption, but no one at the time did all they could to ensure that these interests were fairly represented.*

Some Law

The South Carolina Supreme Court viewed these facts as consistent with the language and purpose of the Indian Child Welfare Act, and it’s not hard to see why. The law was passed 35 years ago because Congress was concerned with adoption practices that separated large numbers of Native American children from their parents (and their heritage). In plain English, having for centuries implemented policies and practices which shattered the centrality of Native American family life, federal lawmakers tried to do something remedial about it. From an amicus brief filed in the case by current and former members of Congress:

Congressional inquiry over several years [in the mid 1970s] demonstrated the severity of the problem: a large percentage of Indian children — one-quarter to one-third — were being adopted or placed in foster care families outside of the Indian tribes; state adoption policies provided little to no protection for maintaining the tribal affiliations of these adopted Indian children; and the loss of millions of acres of tribal lands at the turn of the twentieth century rendered the continued existence of an Indian tribe’s sovereign identity dependent on the tribe’s ability to maintain its future generations of citizens — citizens who would learn the tribe’s language, practice its traditions, and participate in its tribal government, regardless of whether they lived on or off a reservation.

The purpose of the law was to help protect Native American parents like Brown by preventing the “involuntary removal” of Indian children as well as any voluntary adoptions — like this one — which did not give preference to the child’s Indian relatives. It was designed to help keep Indian families together — or at least to give Indian fathers a better chance at keeping custody of their children. In recognizing the purpose of the federal law, and the concomitant need to protect Indian children from having their lives determined by non-Indians, the South Carolina Supreme Court cited a tribal chief’s poignant Congressional testimony:

One of the most serious failings of the present system is that Indian children are removed from the custody of their natural parents by nontribal government authorities who have no basis for intelligently evaluating the cultural and social premises underlying Indian home life and childrearing. Many of the individuals who decide the fate of our children are at best ignorant of our cultural values, and at worst contemptful of the Indian way and convinced that removal, usually to a non-Indian household or institution, can only benefit an Indian child.

The law has been successful — but not entirely. There will be no argument here that the law must be struck down because it has achieved its goal. In their amicus brief in the case, Indian rights groups point out that “recent analyses of national child welfare data indicate that the out-of-home placement of Indian children is still disproportionate to the percentage of Indian youth in the general population and that Indian children still continue to be regularly placed in non-Indian homes.” The law also has been consistently upheld by the justices in Washington as a constitutional exercise of Congress’s authority over Native American affairs.

Matt and Melanie Capobianco

All sides agree that the key legal question in this case is essentially a definitional one. The adoptive couple, Matt and Melanie Capobianco, argue that Baby Veronica’s Indian father “unceremoniously” renounced his “parental rights to his unborn daughter” and thus forever waived his rights to be considered an Indian “parent” under federal law. They say that South Carolina’s law would not have required his consent to the adoption and that the Indian Child Welfare Act wasn’t designed to protect the rights of Native American parents. From their brief:

The state court’s application of ICWA here transformed a statute that prevents the removal of Indian children from their homes into a statute that required the removal of an Indian child from her home …The court held that an unwed biological father of Indian lineage who has abandoned a pregnant mother and child may veto the non-Indian mother’s lawful decision to place her child for adoption, even though under state law the father lacked custodial rights and his consent was not required for the adoptive placement.

But the state courts disagreed. Regardless of how state law might have resolved the dispute, the judges ruled that the girl would never made it to South Carolina, and into the Capobianco’s home, had the couple followed federal law. Brown was a “parent” under the ICWA, two state courts ruled, because he was the girl’s “biological parent” who had established his federal rights by “acknowledging his paternity … as soon as he realized” the girl had been put up for adoption. His waiver of his parental rights was invalid, the South Carolina courts concluded, because the adoptive couple “did not follow the clear procedural directives” of the federal law.

This is all wrong, the Capobiancos told the justices, and a grave injustice is going to occur if Baby Veronica gets to stay with her father. Federal law “does not countenance the chaos and heartbreak that would ensue if tribes or noncustodial fathers with no right to object to an adoption could later uproot Indian children from their adoptive families.” Of course, the “chaos and heartbreak” over adoptions that took Native American children away from their families and tribes is the very reason why Congress enacted the Indian Child Welfare Act in the first place. At least in this case, it appears the Indians have the letter of the law on their side.

Turning Equal Protection on its Head

This is another case where state law conflicts with federal law — which means it is yet another Supreme Court case involving principles of federalism and states’ rights. Enter Clement, the conservative lawyer, who on behalf of the child’s guardian (more on her later), has filed a jaw-dropping brief. Clement doesn’t just want to win for the Capobiancos. He wants also to undermine Congressional authority over the ICWA and all federal Indian law, and he wants to do so not just for this client but for another client, a non-Indian gaming client (who, as you might imagine, also has great eagerness to see the demise of federal Indian law).

So the federalism argument is here. And Clement also makes explicit some of the ugliest threads of this story. Brown doesn’t deserve to have custody of his daughter, Clement argues, in part because he has only “a sliver of genetic material” making him a Native American. The child is “predominantly Hispanic with some Native American and Caucasian background,” Clement writes, as a prelude to his argument that the little girl’s equal protection rights have been violated because the ICWA is a law based unlawfully upon race. Got that? By protecting Indian fathers and Native American heritage, the federal law unfairly burdens white people.

This is another version of the same argument conservatives like Clement have made with such force recently in their challenge to affirmative action and the Voting Rights Act. In this view, the federal law which gave Baby Veronica back to her father wasn’t a laudable shield protecting Indian families from questionable adoptions, but rather a “race-based preference” that lifts Native American fathers to an unlawfully exalted place in custody law. Because it’s a law based on race, Clement then argues, the statute must be evaluated by the courts using the toughest constitutional standard of review. It can’t withstand that review, he writes.

The Justice Department

The Obama Administration sides with Dusten Brown and the federal law upon which he relies. “The South Carolina court properly awarded custody of Baby Girl to Father,” wrote Justice Department lawyers in their brief to the justices. The federal law applies to any “child custody proceeding” involving an “Indian child,” the feds argue, and it is “uncontested that those two predicates are satisfied here. The Capobiancos, the feds wrote, seek a “judicially-invented exemption to the ICWA” that would allow state judges to circumvent it whenever they feel they are justified in doing so. The text of the federal law is clear, they say, and it covers this case.

The “exemption” the feds mention here is likely the reason the justices took this case. Some states have tried to evade the mandate of the ICWA in cases where “the adoption is voluntary and is initiated by a non-Indian mother with sole custodial rights.” But most other states have refused to recognize such an exemption. It’s hard to imagine the justices not resolving this case without resolving that conflict in the way the federal law has been interpreted. The exemption is “particularly problematic,” the feds contend, “because, as sometimes applied in the lower courts, it requires assessment of the ‘Indianness’ of a particular parent or child.”

The Justice Department also responded to Clement’s equal protection argument by briefly — perhaps too briefly — telling the justices that the ICWA is based entirely on political, not racial, classifications. Both biological parents of Indian children — whether both are Indian or not — have rights under the federal law, the feds say. Moreover, “the definition of ‘Indian child’ does not comprise all children who are ethnically Indian,” the feds write, “but rather only those who are members of federally recognizable Tribes or are eligible for membership and have a biological parent who is a member of such a Tribe.”

Postscript

When you don’t have the law, you argue the facts. When you don’t have the facts, you argue the law. And when you have neither the law nor the facts on your side, you argue for equity and justice. The adoptive couple, the Capobiancos, have been out and about telling anyone who will listen that the Indian Child Welfare Act “is destroying families” and has, in fact, destroyed theirs. Technically, it has done exactly that. Without it, Brown would not now have custody of the girl. But that begs the question of the case — did the Capobiancos have the legal right in the first place to take the girl home to South Carolina?

Inevitably, I suppose, this spin campaign has brought with it religious and racial overtones that surely trigger terrible memories for Native Americans, whether in the end they really care about Baby Veronica or not. For example, there was a popular online petition to amend the federal law — in which Baby Veronica’s return to her biological father is considered a “human rights” violation and Indian tribes are deemed to have “unjust power to remove children from happy, healthy homes.” And there is the work of the Christian Alliance for Indian Child Welfare, with a website dedicated to “saving” Baby Veronica by returning her to the Capobiancos.

And then there is the unseemly role of the guardian in the case, a woman who demonstrably has no business being involved in any case involving the rights of Native American citizens, be they little girls or adults. The guardian, according to Brown’s brief, told him that “she knew the adoptive couple prior to the child being placed in their home,” that the Capobiancos could afford to send the little girl to private school, and that as a result Brown’s family “really need[ed] to get down on [their] knees and pray to God that [they] can make the right decision for this baby.”

At first, the brief alleges, the guardian ignored Baby Veronica’s Indian heritage, but then said “that the advantages of Native American heritage “includ[ed] free lunches and free medical care and that they did have their little get-togethers and their little dances.” This is Paul Clement’s client. And this is part of the record of this case. It shouldn’t be about religion. It shouldn’t be about which family can provide this little girl with tuition. It shouldn’t be about white perceptions of Indian culture. It should be about whether or not the justices are going to support efforts to protect Indian families in the fashion set forth in the ICWA.

Indeed, this law is a rare example where Congress actually did something right by the Indians, by creating a national standard designed to preclude the type of state-centered “home-court advantage” symbolized by the attitude of the guardian in this case. The law adds a layer of protection for Indian fathers who face the possibility of losing their children in adoption to couples like the Capobiancos. And it refuses to reward adoptive parents who have failed to properly notify the biological fathers of Indian children that they are about to lose custody of their kids — as the South Carolina courts found in this case.

Cases like this are among the most difficult the justices ever have to decide. If you don’t believe me, ask Justice Antonin Scalia, who last fall cited an ICWA case from 1989 as one of his hardest in 27 years on the Supreme Court bench. They are difficult because there is only one child and two families seeking to raise her and thus no wiggle room for Solomon’s compromise. The Capobiancos surely deserve to have a child of their own. And so, federal law says, does Dusten Brown. In this instance, at least, the white man’s burden figures to be too much to bear.

* A lawyer for Baby Veronica’s mother contests these facts, argues that the Cherokee Nation was properly informed of the adoption, and contends that both the Nation and the Bureau of Indian Affairs now acknowledge they received timely and adequate notice. Brown and the Nation, in turn, dispute these characterizations. The Bureau of Indian Affairs acknowledged proper notice only after Brown had begun his lawsuit to stop the adoption, they say. So far, as set forth above, the only two courts which have reviewed the facts of this case have sided with Brown and the Cherokee Nation.

Quietly, Indians reshape cities and reservations

A mural painted by children at the Little Earth of United Tribes housing complex in Minneapolis.

Published: April 13, 2013 in The New york Times

MINNEAPOLIS — Nothing in her upbringing on a remote Indian reservation in northern Minnesota prepared Jean Howard for her introduction to city life during a visit here eight years ago: an outbreak of gunfire, followed by the sight of people scattering.

She watched, confused, before realizing that she should run, too. “I said: ‘I’m not living here. This is crazy,’ ” she recalled.

But not long afterward, Ms. Howard did return, and found a home in Minneapolis. She is part of a continuing and largely unnoticed mass migration of American Indians, whose move to urban centers over the past several decades has fundamentally changed both reservations and cities.

Though they are widely associated with rural life, more than 7 of 10 Indians and Alaska Natives now live in a metropolitan area, according to Census Bureau data released this year, compared with 45 percent in 1970 and 8 percent in 1940.

The trend mirrors the pattern of millions of African-Americans who left the rural South during the Great Migration of the 20th century and moved to cities in the North and West. But while many black migrants found jobs in meatpacking plants, stockyards and automobile factories, American Indians have not had similar success finding work.

“When you look at it as a percentage, the black migration was nothing in comparison to the percentage of Native Americans who have come to urban areas,” said Dr. Philip R. Lee, an assistant secretary for health during the Clinton administration and an emeritus professor of social medicine at the University of California, San Francisco.

Recent budget figures show that federal money has not followed the migration, with only about 1 percent of spending by the Indian Health Service going to urban programs. Cities, with their own budget problems, are also failing to meet their needs.

One effect of the move toward cities has been a proliferation of Native American street gangs, which mimic and sometimes form partnerships with better-established African-American and Latino gangs, according to the F.B.I. and local law enforcement reports. Last month, a federal jury in Minneapolis convicted several members of the Native Mob, a violent gang, of racketeering and other crimes as part of one of the largest gang prosecutions ever undertaken in Indian Country.

The migration goes to the heart of the question of whether the more than 300 reservations in the United States are an imperative or a hindrance to Native Americans, a debate that dates to the 19th century, when the reservation system was created by the federal government.

Citing generational poverty and other shortcomings in reservations, a federal policy from the 1950s to the 1970s pressured Indian populations to move to cities. Though unpopular on reservations, the effort helped prompt the migration, according to those who have moved to cities in recent years and academics who have studied the trend.

Regardless of where they live, a greater proportion of Indians live in poverty than any other group, at a rate that is nearly double the national average. Census data show that 27 percent of all Native Americans live in poverty, compared with 25.8 percent of African-Americans, who are the next highest group, and 14.3 percent of Americans over all.

Moreover, data show that in a number of metropolitan areas, American Indians have levels of impoverishment that rival some of the nation’s poorest reservations. Denver, Phoenix and Tucson, for instance, have poverty rates for Indians approaching 30 percent. In Chicago, Oklahoma City, Houston and New York — where more Indians live than any other city — about 25 percent live in poverty.

Even worse off are those living in Rapid City, S.D., where the poverty level stands at more than 50 percent, and here in Minneapolis, where more than 45 percent live in poverty.

“Our population has dealt with all these problems in the past,” said Jay Bad Heart Bull, the president and chief operating officer of the Native American Community Development Institute, a social services agency in Minneapolis. “But it’s easier to get lost in the city. It’s easier to disappear.”

Despite the rampant poverty, many view Minneapolis as a symbol of progress. The city’s Indian population, about 2 percent of the total, is more integrated than in most other metropolitan areas, and there are social services and legal and job training programs specifically focused on them.

The city has a Native American City Council member, Robert Lilligren; a Native American state representative, Susan Allen; and a police chief, Janee Harteau, who is part Indian. But city life has brought with it familiar social ills like alcoholism and high unemployment, along with less familiar problems, including racism, heroin use and aggressive street gangs.

Continue reading here.